|

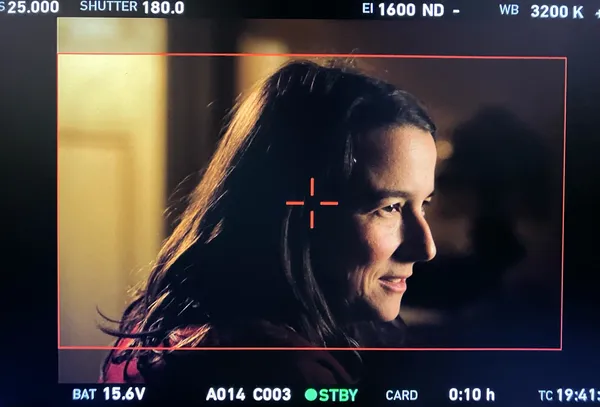

| Sarah Lasry on the set of Hotel Acropole |

"What a film. What a filmmaker," were the impactful words Fantasia's Mitch Davis chose to describe French filmmaker Sarah Lasry's short film Hotel Acropole. Rivka (Judith Zins), a pregnant woman, is grieving the loss of her husband. Since his death, she has been afflicted by a wound on her back that will not heal. The day before she plans to scatter his ashes, she checks into Hotel Acropole, where a visitor, Abel (Sébastien Houbani), intrudes on her self-imposed isolation.

The filmmaker backs up Davis' hype by creating space for the audience to enter the film and filter it through their own ideas and experiences. Hotel Acropole can be experienced for its visceral horror and eroticism, as well as philosophical and intellectual themes and ideas. It's a film that works on both a conscious and unconscious level and creeps under our skin to leave us with a feeling that can be difficult to articulate. And it's the type of film that quietly rather than bombastically asks each spectator to reckon with its layered narrative.

Lasry's previous film, Spell On You, told the story of Salomé, a little girl who has a mysterious wart appear on her nose. Disgusted by her appearance, her parents, who she spies on, take her to the doctor, who struggles to offer any answers.

In conversation with Eye For Film, Lasry discussed capturing the nuances of sexual intimacy that are often ignored, using body horror as metaphor and imbuing Hotel Acropole with the unreal. She also reflected on a diverse range of creative influences across film, literature and photography, and the necessity of confronting our fears.

Paul Risker Why filmmaking as a means of creative expression? Was there an inspirational or defining moment for you personally?

Sarah Lasry I think when my parents were on the verge of splitting up, I was always borrowing my Dad’s handheld camera, and I just started filming everything. It was like a way to keep the trace of a moment in my life. I was 11-years-old, but unconsciously, I was aware that something was shifting and that I needed to keep track of it.

|

| Sarah Lasry filming Hotel Acropole |

That same year, my mom took me to the cinema to a screening of Vertigo. I had seen other Hitchcock films like The Man Who Knew Too Much, but seeing Vertigo in the cinema was a mind-blowing experience. When I got home, I read the book Hitchcock/Truffaut where the French director François Truffaut interviews Alfred Hitchcock, who dissects his films and explains how each shot was thought-through and made. I definitely became aware that I wanted to tell stories through the medium of film at that point.

PR: The obsessive nature of its story has made a lasting impression on me, alongside Hitchcock's use of colours and even animation in its one sequence. Vertigo is made up of these narrative and aesthetic layers that seduce you in different ways.

SL: Every time I watch it, I see something new, and I understand it differently at various moments of my life. The first time I saw it, I don’t think I understood everything, but like you say, I was obsessed by it. And certain scenes or frames absorb us, but we can't really explain why. There's the image of Kim Novak coming out of the bathroom in the green light, or seeing her from behind when she's sat in the museum, in front of the painting, with her blonde bun. Then there are the shots of James Stewart stalking her in the city. These images still haunt me.

PR: Hotel Acropole might offer audiences a similar experience by allowing them to shape the story's meaning on their own terms. One reason I mention this is because for me, having read the synopsis, the experience was different to the expectations I went into the film with. I'd go as far as to say I watched a different film.

SL: I understand… Writing a synopsis is such a strange exercise! But in a way, I’m glad that you didn’t see what you expected.

In the editing process, I try and let my unconscious guide me because I think it's good not to be too aware of what we're doing and to also allow ourselves to be led by our emotions. Sometimes something will feel right even if it's not rational.

As a spectator, I don't like to be fed what I'm supposed to think or feel. So, what I'm trying to do is give the spectator the autonomy to project their own images onto what they're watching.

PR: What compelled you to believe in this film and decide to tell this story at this particular point in time?

SL: I wrote a very early version of this story twelve years ago while I was pregnant, and then it kept evolving over the years. The starting point was this vision of a woman who has a wound on her back that can’t heal, and progressively it became a metaphor for her grief.

I knew I’d have a small budget and limited time to make it. I finished writing it coming out of Covid and I wanted to evoke our fear of touching another person’s body. The film needed to be simple production-wise, so I wanted one setting with two actors, inspired by films that are two-handers in a bedroom.

An important influence on this would be the bedroom scene between Nicole Kidman and Tom Cruise in Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut. They're just talking, but there's something completely fascinating about it as they discuss their fears and fantasies, and they confront each other on the subject of their relationship and desires. It's similar to certain fascinating scenes in Sex, Lies And Videotape by Steven Soderbergh, where the characters tell each other intimate secrets about each other. Or in Chantal Akerman's Je Tu Il Elle, there's this amazing sex scene at the end of the film, where two women make love for about 12 minutes without any dialogue, and the takes are very long, with hardly any editing. It’s such a beautiful, real moment — so honest and raw.

|

| Sébastien Houbani in Hotel Acropole |

I also wanted to make this film because I wanted to film sex through the genre of body horror. There's so much that can be said about what happens during sex, whether it's power dynamics or the relationship between people without words, that we don't really take the time to reflect on or film. I wanted to express these feelings of pleasure and pain, as well as a feeling of guilt attached to sex, that sometimes makes it even more exciting. All these elements were important starting points during the writing process.

PR: The sex scenes in Nicolas Roeg's cinema remain some of the most captivating because he allowed sex to exist on its own terms and not to be convoluted by ideas of eroticism and sensuality. This is a rarely seen tact, but when sex in cinema is approached in this way, we begin to get closer to something genuine.

SL: I don't know if you’re thinking of Don't Look Now, but the scene in that film between Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie is amazing because it's also a film that talks about a couple trying to overcome grief. The sex becomes part of the narrative. The way Roeg uses time is also very powerful. But there's something about the films that were made in the Seventies that were so much freer. Films like An Unmarried Woman by Paul Mazursky, Girlfriends by Claudia Weill or Opening Night by John Cassavetes.

I’m also influenced by experimental films from the 1960’s — filmmakers based in New York, like Yvonne Rainer and Jack Smith, who mixed film with performance and dance. To me, that’s the pleasure of making short films: allowing ourselves to play with more experimental images. With Manuel Bolaños, my cinematographer, we were also inspired by the photographer John Coplans and his work on the naked body.

I loved showing Hotel Acropole at Fantasia Film Festival in Montréal because people were screaming in the theatre, either from surprise or disgust. Hearing their gut reactions in a large audience was so interesting because you can watch the sex as an erotic scene, but it can also be perceived as horror. And I like that there's this weird mix of feelings, where we’re not sure what we’re supposed to feel. It's the same in life.

PR: I personally viewed it as an emotionally wrought reflection on human nature, that addressed feelings of guilt and shame, and the struggle to have compassion for ourselves within a moral struggle. So, in more of a philosophical context, I suppose.

SL: Yes, of course. It's hard to talk about, but I feel these are universal feelings we can all identify with. It's hard to get over the guilt when you don't necessarily behave in a way that's moral. I don't want to judge my characters. I'm interested in those moments where we don't necessarily act in the way we should. The two characters are attracted to each other, but it’s an impossible and forbidden love story, which only makes it more thrilling. It's wrong, but they can’t stop themselves. So how do they deal with it?

PR: Hotel Acropole reminds me of Shirley Jackson's short story The Intoxicated, about a party guest who quietly chats with his host's young daughter. Similarly to the scene from Eyes Wide Shut, Jackson's short story is self-contained, and like your film, it's also deceptively simple.

SL; It's funny that you talk about Shirley Jackson, because she's a huge influence. What I love about her writing is that there's always this hidden humour — it's probably very British. There's just this very dark, twisted humour that also says something about human nature in such an honest way.

We should never underestimate simplicity. I think my film could also be viewed as a fantasy. There's something unreal about it. During the sound edit, we first added naturalistic sounds of the hotel, to hear other clients, or people working there. But we realised while mixing it that the soundscape needed to be ghostly, uncanny, strange… Not a realistic space.

|

| Sébastien Houbani and Judith Zins in Hotel Acropole |

In The Eternal Daughter, director Joanna Hogg really plays with that bizarre atmosphere, filming the hotel like a strange space outside of reality, and I love that. It's almost like science-fiction.

In our choice to film the female body as a mysterious territory that is frightening and possibly disgusting, Hotel Acropole could almost be seen as a witch story in some sense. But I liked the idea of filming a man who's not afraid, disgusted or turned off by her body. Instead, he sees this strangeness as something beautiful and even exciting.

During the sex scene, I didn't want to add music. Instead, I just wanted to hear the actors breathing and hear the sound of the wound. That was all I was interested in. As a spectator, I take a lot of pleasure in seeing that simplicity and not having anything artificial or unnecessary added to the mise-en-scène.

PR: By paring back the artificial elements, you expose the audience to the film's natural soundscape, whether it be their physical intimacy or the moments of silence where there's only the hum of their presence. Too often films drown out this textured soundscape in favour of the artificial. To break from tradition, however, risks pushback from the audience.

SL; It can be off-putting in the beginning because it scares people — if there is silence, how do you deal with that?

In this film, it's an awkward type of silence, and I'm really interested in this awkwardness. My editor, Guillaume Lillo, and I do a lot of work around this. Sometimes we'll do cuts of the film, and he'll say to me, "No, that's too easy because it's too fluid. The rhythm works too well. So, it's too comfortable. And if we're too comfortable as viewers, then it's not interesting enough." So, it's about looking for those spaces and silences, because in life, there are those moments where it's not comfortable. That sometimes becomes an interesting task in the editing room.

PR: Returning to an earlier part of our conversation, you spoke about respecting the audience's autonomy. Were you suggesting that a film starts off being about the characters and ends up being more about the audience?

SL; I think it’s about both. It’s really a struggle because when I'm editing, I try to break free from the temptation of making something too clear or obvious. I think the film is also a mystery the viewer needs to figure out on their own. It's about allowing ourselves to watch a film and being drowned by our own emotions and our own associations — our unconscious, because watching a film is also a time for the spectator to reflect.

Coming from experimental theatre, I always like this idea of making the spectator an active participant or even a co-writer of the story. I have my own intimate perception, of course, and my story to tell, but I like that you can have your own interpretation when you're watching the film. I don't want to make films with a message that tells the audience what to think.

PR: So, a film is also an invitation for the filmmaker to self-reflect.

SL: Of course. I grew up in a household where my parents’ love life was extremely present and overwhelming, which is what my last short film was about. What I realised is that when I got older, I was unconsciously reproducing what I'd seen at home — the same patterns and fear of betrayal. And so, the love triangle is really the story of my life and what I’m obsessed with. In every piece I’ve written, it's always about a threesome in some way.

The two actors, Judith Zins and Sébastien Houbani, acted in my previous short film, Spell On You. There was something in their onscreen chemistry that I was interested in exploring in a deeper way. So, I incorporated what I knew from them into the writing.

|

| Sébastien Houbani and Judith Zins in Hotel Acropole |

When I'd written a first draft of the script, we went away together for a few days, where they improvised different scenes around the film. A lot of what is in the film emerged from these workshops, and in many ways, a film is always a documentary about the actors.

PR: It's an idea that speaks about being vulnerable, because you and your actors have to embrace and be willing to share your vulnerability. At the same time, the audience has to be emotionally open to connect with the characters and the story.

SL: The cynic inside of us has to let go because there is something very romantic about this as well, especially when Abel tells Rivka what he will never do to her body again. It’s an erotic text. There’s a lot of humour in it as well, but you can’t be a cynical spectator. The film is deeply romantic, and you have to just let yourself be engulfed by the character’s desire and not be afraid to hear it. In today’s society we are so afraid to say these words and take them seriously. But love and desire are a very serious thing.

PR: How do you look back on the experience of making Hotel Acropole, and would you describe it as a transformational experience?

SL: I feel extremely grateful to have worked with such a wonderful team in a very limited timeframe and budget. It was a true challenge, but everyone’s hard work really shines through. I think making the film taught me to be less afraid of my own desires as a filmmaker and during the process I had to focus on listening to my crew, while trusting myself and my instincts. The more we delve into confronting our own fears, the more honest we are in our work. Understanding this was transformational for me.

Hotel Acropole premiered at the 2025 Fantasia International Film Festival.