|

| Moon Guo Barker in Mare's Nest. Ben Rivers: 'For me, it was very important to not have conflict in this film' Photo: Ben Rivers |

What came first, the wish to work with Moon or the idea of a world of only children?

Ben Rivers: I was thinking about making a film with children and just starting to piece some ideas together in my head but it was very vague. Then I thought about working with Moon, and I asked her if she'd be up for being in a film and she said, “Yes”. Then the film really started to take shape because I had a really great human to imagine moving through it.

I understand this film had an unusual production history, can you tell us about that?

Andrea Queralt: I've known Ben for a while now, and we already tried to work together in the past. I've always admired his work and his liberty when shooting when scheduling his work and the fact that he's so faithful to his desire and, unfortunately, sometimes production structures and funding cannot really match this type of liberty.

|

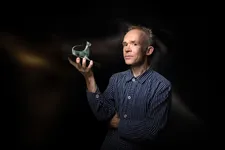

| Ben Rivers with his Green Leopard Photo: Locarno Film Festival/Ti-Press |

Ben, you normally edit your own films but this time you brought in Armiliah Aripin, can you tell us about that choice?

BR: I do, normally, because it's the part that I really enjoy doing, you know, because in the end, it’s kind of where you make the film. The way that I make films, they change a lot in the edit and they kind of evolve. But with this one, I think especially with the Don DeLillo, it felt a little bit out of my depth, it's not really my territory to edit, to edit a really intense amount of dialogue. So I asked Armiliah if she'd be interested in just having a crack in it and she had a crack at it and it was great.

Armiliah Aripin: I remember Ben saying when we were editing, “This is maybe the most number of cuts I've had”. Whatever Ben does, I’m a fan of it but that’s not my area, so I thought it’d be interesting to try this out. I quite enjoy editing what I like to call ‘dinner scenes’, where people just sit around and talk to each other. I think it's really fascinating seeing how people react to things as opposed to what they're saying. And then the DeLillo is just a great script to work with. So, yes, thanks Ben for having me, doing it was really fun.

How did you get DeLillo’s text? Did you discuss it with him?

BR: We had a little bit of contact a couple of years earlier. He’d seen a couple of my films and written a really nice letter to me, which is framed. Then when I came across the play The Word For Snow. At first, I thought I'd like to do something with it, maybe just as a play. But then, at the same time, I was thinking about making this film with children. I thought, actually, I can include it within the film and putting those words into younger people’s mouths would just give them even more power. I asked him if I could use it and he said, “I don’t see it as a film but feel free to try”. They were very kind. They didn’t ask for much money. They’d just made a lot of money selling White Noise, so they let me have it for about a thousandth of the price.

Tell us about the remarkable locations?

|

| Ben Rivers: 'When I saw the labyrinth it was really obvious I needed to make a minotaur' Photo: Ben Rivers |

So a lot was shot in Menorca and some in North Wales, when we wanted some of it to have not such good weather. With The Word For Snow, we built the set. The hut is a closed set. The end was on mainland Spain, the Monegros desert. We were looking around for deserts and, with the help of the team of Sirât, which Andreas worked on as well, we dropped by their se and ended up filming.

You mention, we have myth to protect us when history goes mad, was that also partly your motivation for making this film, since history does seem to be going mad at the moment?

BR: Definitely. That was the catalyst for the film – what kind of world are we living in. What kind of world are the children inheriting from a sort of disastrous human society? It’s not pretending to be some kind of answer but thinking about, what if in some completely hypothetical situation, there are no adults left and we're just left with children and they're kind of starting from scratch. That’s disturbing but there’s a sort of hopefulness to it. There’s some kind of potential to think beyond the sort of structures that we’re locked in, based so much around greed.

I don’t believe this Lord Of The Flies idea that if you leave a bunch of kids together, they'll necessarily hate their elders and become violent and have conflict. For me, it was very important to not have conflict in this film, which is completely antithetical to any script writing course you might do because you're told you need conflict to make a film – and I was very adamant that this was going to be without conflict. It’s important to make the films that I want to make, that I feel seriously compelled to make and to try to make them as honestly as possible and if that means not fitting into certain commercial needs and structures, that’s fine. I think the important thing is to make the film you believe in each time and hopefully there’s at least some kind of audience there for you.