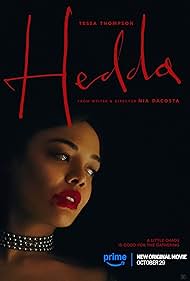

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Hedda (2025) Film Review

Hedda

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Since its première in 1891, Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabbler has been produced for the stage on dozens of occasions, adapted as a musical, as a ballet, as a radio play, as a television drama and, on at least three occasions, as a feature film. Even with such rich material, it’s understandable that potential backers might wonder what remains to be said. Nia DaCosta’s innovations are not wholly new – there has been at least one prior version with lesbian characters – and yet by combining that with the casting of a black lead (the impressive Tessa Thompson), DaCosta has managed to create something which feels acutely contemporary and fresh.

The colour of Hedda’s skin – though it is remarked upon directly only once – makes her ascent into the upper middle classes all the more remarkable. It positions her desire for the trappings of the aristocracy – most notably the ravishing late Georgian house for which her smitten husband, George (Tom Bateman) has near bankrupted himself – as a form of glorious rebellion, almost a political act; and the fact that she can look glorious herself in the sort of costumerie which heritage films traditionally reserve only for white women gives her a degree of heroic status before the narrative begins. Her awareness of the precarity of all this, meanwhile, goes some way towards explaining her ruthlessness. In a tale in which others find themselves fighting for survival, she has been fighting all her life for a shot at something bigger, more marvellous, and her success, for all its limitations, makes all sorts of things seem possible.

The story is set in England in 1956. England did not get its first Black judge until the late 1970s, so the casting of that character is a little anachronistic, but Nicholas Pinnock has the gravitas to carry it, and it immediately hints that he too is capable of ruthlessness when the occasion requires it. Meanwhile, the character of Eilert, Hedda’s former lover and George’s academic rival, becomes Eileen (Nina Hoss), whose achievement within a male-dominated sphere is something different. Open about her sexuality in stark defiance of the mores of the time, she has enjoyed a degree of success anyway, simply due to her brilliance. Her willingness to be herself gives her the kind of freedom that Hedda longs for – the thing she has sacrificed – meaning that there is yet another reason for the younger woman, if she cannot possess her, to want to destroy her.

DaCosta sets her cards on the table at the outset by reinventing the story’s end. This was always one of the most difficult parts of the original to swallow, a believable consequence of exhaustion and panic but not otherwise true to character, and it would be even less fitting for this altered version. The other change which arguably enables it is itself intriguing, opening up as it does a further set of possibilities. But it is the manner of the principal change which really makes things interesting, and points up the Gothic aspects of the tale, because followed as it is by a scene of Hedda playfully shooting at the judge from the roof as he approaches at the start of the party, it knocks time out of joint, making it seem circular. There is a sense that the characters – and most notably Hedda herself – are trapped within the house, playing out their fates again and again, influenced emotionally by prior cycles yet unconscious of them. There is a different species of horror to this, a different way of reckoning with the experience of love and the Sisyphean effort involved in social climbing.

As for the tale itself, DaCosta pulls out all the stops. The house itself is necessarily splendid, the costumes gorgeous even when they are better suited to characters’ ambitions than to the characters themselves. Hedda’s nervous flitting around during early scenes in which the capacious rooms are slow to fill up reveal another aspect of her vulnerability, an outsider queen who cannot guarantee that she will have a court, for all the eagerness with which she is courted whenever her husband turns his back. The music, selected by DaCosta herself, fits the tale’s shifting moods perfectly and packs more of a punch than most viewers will expect.

We get a proper sense of how young Hedda is, how easily she is emotionally jolted. There’s a naivety about her which, for all her scheming, is quite sweet, captured in little incidental faux pas and moments when she looks briefly overwhelmed. In conversation with Thea (Imogen Poots), Eileen’s new young girlfriend, she is petty as a schoolgirl. Thea seems more lost, of course, but less afraid of admitting it. Poots plays her as if she were a different kind of instrument, a penny whistle in the orchestra, charming in her own right but unable to complement the others’ performance.

Eileen doesn’t care; and when she arrives, a long tracking shot grabs the viewer’s attention as she has grabbed Hedda’s. In due course she too will have her moments of naivety and clumsiness, the comedy they produced tinged with a sense of danger. No amount of finery can mask the impression that all three women are navigating an essentially savage environment. Nevertheless, fellow feeling between academics grants Eileen some leeway, some ability to interact on an equal footing with men, which Hedda, for all her tough talk and love of guns, cannot do.

Compared to many who have played the leading role (including Hoss), Thompson is a slight figure, but this makes the intensity of Hedda’s passions seem all the more volatile: concentrated, under constant pressure. She may play play petty games, but everywhere she is seeking opportunities, testing boundaries. Thompson marries her ferocity with a keen intelligence which, though she may lack the intellectual sophistication of others at the party, she nevertheless deploys to her advantage. This quality, too, makes the lot of a loyal and patient wife seem intolerable. It is ostensibly George who she wishes to advance, but he is not her equal. Where he does surprise her is with qualities she does not seem to possess at all, and there the film finds a note of hope which speaks to the larger, shifting narratives of our time.

Executed with supreme confidence, as beguiling as it is shrewd, this is a film which can stand proudly alongside the classics of the heritage tradition. One only hopes that it is not too heavily compromised by its place on Netflix. Though it can still work in this more restricted setting, it belongs on a big screen.

Reviewed on: 29 Dec 2025