|

| Richard Hawkins on Think Of England: 'The intention was just to jar people out of a kind of storytelling complacency' Photo: Courtesy of POFF |

His prologue informs us that, at the same time as Winston Churchill was telling Laurence Olivier to make Henry V as patriotic propaganda, a second filmmaking plan was in action to film three hardcore pornography shorts in a bid to keep up the men’s morale on the frontline.

The edict means a motley crew of six are assembled on the island each with their own reasons for being there – Captain Clune (John McCrea), costume and make-up assistant Agnes Dupré (Ronnie Ancona and her 18-year-old son Clifford (Ollie Maddigan), German Jewish director Max Meyer (Ben Bela Böhm), acting hopeful Holly Spurring (Natalie Quarry) and bona fide but war-damaged movie star Tyrone Higgs (Jack Bandeira). As the shoot starts, and another presence is revealed on the island, Hawkins probes this battleground of moral boundaries, censorship and propaganda.

The film had its world premiere at the Black Nights Film Festival in Tallinn and will have its UK premiere at Glasgow Film Festival next month.

This is quite an unusual satire in that many people may not realise that they're watching a satire even as the film finishes. I’m curious as to why you've decided to smuggle that in because you don't tip your hand, even at the end. I’m not even sure whether it’s a spoiler or not to talk about it, so I’m interested to know what you think.

Richard Hawkins: I don’t know whether it’s a spoiler or not a spoiler. I’ve always wondered. I think what I wanted, more than anything with this entire film, was that an audience would walk out of the cinema and at first thought would be, “What the fuck is that?” And their second thought would be: “Let’s Google it.” And, thereby, this process would begin of them re-evaluating and a lot of the film is about that. That re-evaluating everything. In the land where we live, without wanting to be political, you know, the truth has become incredibly subjective and and I notice everyone seems to have no issue with their news being 92% total fabrication and yet the moment I try to do it in fiction. It's kind of outrage.

|

| Director Richard Hawkins on location: 'We had weather warnings and the 21 days to do this film was incredibly challenging' Photo: Richard Hawkins |

I'm a fiction writer and a dramatist. It's my job to tell, I believe, a psychological truth and that’s what I wanted to do. I almost wrote the story with my story writing partner backwards from the epilogues so I could believe in these people entirely and then I felt I really want that as part of the journey because it gives a historical context and the film is about hunting for people's truths.

The characters themselves attempting to find their own truths and history itself trying to find its own truth, which is often inconvenient, and an audience watching the film, trying to make sense of this. So it was all about degrees of truth and how elusive it was and it seemed a complete failure to cop out at the end.

Secondly, personally I loathe the phrase, “based on a true story”. I mean, there's nothing lazier and more disingenuous than saying “based on a true story”. Come on, have an original idea and follow it through. I remember Daniel Defoe almost being arrested for Robinson Crusoe, kind of Britain’s first novel in a way, then people read it and it’s, “I was this… I was shipwrecked” and then they find out it’s made up. That was the point, it’s a story. Then you get into really complicated land like, for instance, the Bible or the Koran and when is storytelling storytelling and when is it the truth? So that was the logic of sticking with it all the way through that. Surely good fiction is utterly believable and the proof of the pudding would have been if they’d walked out and believed it even with the epilogues.

You’re definitely convincing because I’ve met people who have believed it. I wonder if some of the outrage is because it makes it tricky for people to review because the question is do you “spoil it” or not and, as you said, is it even spoiling it? Given that the whole thing is satire. At least with a feature I can just put a spoiler warning at the top

RH: It’s part of the fun of the thing. It's meant to be a mischievous film and has not a single answer I could think of and if it has an answer then it’s there accidentally. It’s interesting at festivals because I do Q&As and if it’s not the first or second question, it’s the third, “So how did you find this story” And then you're in that moment of thinking? “Okay, here we go” You can feel it in the audience, half are kind of thrilled and half are very uncertain that I haven't crossed some moral code.

Wartime as well is the perfect setting for a film that’s discussing the invasion of space, the blurring of boundaries. I’m curious as to why you picked the Second World War in particular.

RH: I picked this war because I was telling a story about Cinema and the history of Cinema. The moment cinema was created, there was an immediate panic in the world that we were going to immediately go to that one place we can't go – fucking. So within like a week of the talkies coming out, the Hays code is originally written. It actually became universal in 1934 1934, which out of interest is exactly the same year as Anything Goes was written, which I find such a contemporary song. So we had a value system that says, “This would be catastrophic”.

Then you layer a war on where, on the one hand, you say, “You must not see a breast” and on the other hand, you must say, “Get out there and slaughter everything wearing the wrong outfit”. So in my opinion, nothing challenges the value system that we all hold and adhere quite like war and nothing has told that story quite like film. The Second World War sits at the height of Cinema, it's the Golden Age of cinema. All of this together is why I set it there. Also, it still is the last time a huge amount of us stopped our lives, put them on a massive hold and acquired a completely different dynamic. Bakers were soldiers, school mistresses were nurses on the frontline, everyone put on a costume and for four years changed their entire life. I revisited this in Covid and again it was this moment where we all suspended our normal lives and took on some kind of unified response to a problem. You had the rise of the influence of “woke” simultaneously with the phenomenon of Trump. If you pull those apart, what you realise is going on, is this real fight and struggle for what should be our shared value system. And where is our moral compass? So in a way they were echoing the war which just has to have challenged so many people’s moral compass.

The film is all about crossing lines in various ways and, even in the filming, you're sort of crossing lines, because you're moving from black and white and there's some handheld filming, there's some fixed shots.

RH: Yes, we crossed the line, which you’re not allowed to do, we have those moments when it’s, “Wait a minute, the eye line’s all wrong”. We go from both sides of the camera, pointing back at the crew or the actors, so we quite literally cross the line. The intention was just to jar people out of a kind of storytelling complacency.

|

| Richard Hawkins: 'The really interesting thing about doing it is that the cliched idea of the actress in 2025 is very different from the cliched idea of the actress in 1943' Photo: Courtesy of POFF |

Obviously, the film sets itself up to be the most archetypal, slightly nauseous English period drama with a little bit of seaside naughtiness. So when it goes AWOL, I wanted the audience to be lost and stay lost until they walk out the cinema. Not unsatisfied, I would have failed if that was the case. But I wanted the resolution of the film to come after they watched it. So once we start tripping them up, I hope we carry on.

Tell me about getting the ensemble cast together because the dynamics are crucial.

RH: The really interesting thing about doing it is that the cliched idea of the actress in 2025 is very different from the cliched idea of the actress in 1943. I wanted, for instance, for the Holly role, a woman who the guys would paint on their Lancaster bomber. Likewise for the men, the archetypal tough guy in 2025 is some gym monkey. If you look back at the cinema of the Thirties and Forties, the tough guys aren’t. Their toughness is an innate quality not a physical intimidation. The first challenge was did I believe them.

It must also have presented some challenges for you in terms of intimacy co-ordination as this is the modern world not 1945 and you really drill into the idea that if you’re acting something that’s highly emotional then it can present an issue for the actor as a human being

RH: Yes, personal consequences. I challenge anyone to tell someone to their face, looking them in their eyes that they love them because you can be acting all you want but it still has an effect. The irony here, of course, you could argue Think Of England is an exposition of the advent of intimacy coordination. What do they do? They sit and discuss their difficulties of dealing with what they are doing. The film itself is an act of intimacy coordination.

Actually, despite the subject, your film is quite chaste.

RH: Exactly, because as the film tries to make it clear violence is the absence of sex, in a way. War is the absence of enough love. If you go around the world where violence is ubiquitous you will find the repression of sexuality. Let’s talk about the setting because, in a way, you’re also playing around with truth in that you’ve picked Scotland but it was shot in Wales. And how did you cope with the notorious Welsh weather on the shoot?

|

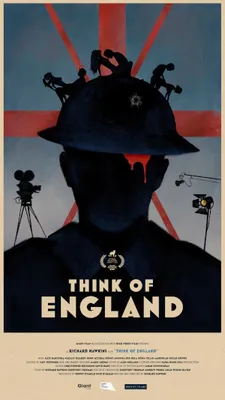

| Think Of England poster |

Think Of England’s UK premiere is at Glasgow Film Festival, where it screens on March 6 and 7, for more information visit the festival website.

Read our interview with the producer Poppy O'Hagan.