Being based in Edinburgh, I remember that day quite vividly. Were you there on the day on Kenmure Street?

Felipe Bustos Sierra: No, I wasn’t. I lived in Govanhill at the time, which is only ten minutes away and my first film Nae Pasaran was on iPlayer at the time and I had friends who lived on the street, and I got the same text that everybody got that morning. Obviously, in hindsight, what a mistake but I just felt this is not going to turn out well.Eight hours later when I saw what happened, obviously, I was massively interested. I've been involved in the solidarity movement my whole life and in the case of people in my family or friends of my family, solidarity meant survival. But, at that point, 40 years in, I had lost faith in mass protests. So, I really didn’t see the hope. I re-shared it like many other people did.

So you were surprised, as many people were, when it did pass off peacefully?

FBS: Completely. It just felt completely new, which is why the next morning I was on Kemure Street and talking with my friends. The magical thing about this film is that we've got all these little pockets of people telling us their story and we get to put it all together. So I think some people who were there on the street all day will discover a new aspect of what happened on the day. That was quite interesting, just how dense that protest was, which meant that some people only experienced it from the perspective of their close or one particular side of the street. It was through a long process, during Covid at the time, and lockdown and the government-mandated 10,000 steps every day of just going around Queen's Park with a different person, every couple of days, and sort of piecing the story together, It was the combination of these conversations, which obviously allowed us to talk about making my friends, including why did you go? Why did you think there was hope? At what point did the hope come in and you thought that something could change. It allowed us to shape the film into something much more than just documenting it itself.

So you more or less decided at the time that you wanted to document it in some way?

Deciding to do this early on presumably helped you in terms of getting hold of people who were involved on that day. Did you have any difficulties in convincing people to speak to you because there are people who have been kept anonymous in this film

FBS: It was a tricky thing of, “What is this for? Why was I researching it and what is it going to become, where is it going to go? What’s the perspective?” It was almost like an extending circle of trust. I’d gone through a lot of social media to find footage and to identify people who were in the right place at the right time, so it would be great to talk to them. Through that word of mouth, and those first six to seven months of the Queen's Park conversations allowed me to pretty much talk to most people who are in the film.

There's an element of safeguarding obviously to the whole film. It’s not like Nae Pasaran where we got to make this film 40 years later so safeguarding is not really an issue there. Here, we’re very much making the film as an ongoing news story. Immigration and the Home Office and the situation are, in many ways, worse than they were then. It was quite interesting in terms of storytelling for these types of stories. I'd gone through, at that point, a lot of press and a lot of Q & A's with Nae Pasaran and in my mind in the mind of the four guys in the film, we had this idea that it was four old men who had done what they could with what they had. Then the film came out and by the process of making a film you're sanctifying these people and you're consecrating them or putting them on a pedestal and they automatically become extraordinary characters. That's rarified air and obviously that wasn't the opinion of myself or that of any of the guys in the film.

So there is a sense, going into this film, that Van Man had gained a sort of mythic quality in the weeks following the protest. As he says in the film, he didn't have much of a plan, he just had an opportunity and it really could have been anyone sliding under that van, repeating that gesture which had happened through the Scottish history of protest many times before with people trying to stop vehicles. It was just the timing opportunity and we wanted to make that clear. And so I think all these conversations led to, “How do we portray this and keep people safe without creating some sort of icon?”

Trying to get across as much as possible the idea that anybody could do this, anybody should do this. Yeah. This is the way we move forward.”

The everyman quality is strong in the film because you made the decision to use crowdsourced footage rather than that from what people would consider “traditional media” like the BBC, for example. Tell me about that decision?

FBS: Authenticity was important. I’m very aware that there have been a lot of disinformation campaigns about what happened on the day. So it was important for us to show we were really making the film out of the footage that had been done on the day and that's all. So there's a difficulty there because often we're working with fragments of footage, just a few seconds. The way people capture things for social media is sometimes on the hoof, treating their phone like a hoover rather than something that's focused and composed and In particular in the moments that have so much interest and urgency. We're trying to sort of place the audience in the same shoes while they're watching the film.

|

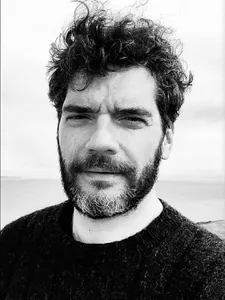

| Felipe Bustos Sierra: 'Authenticity was important. I’m very aware that there have been a lot of disinformation campaigns about what happened on the day' Photo: Courtesy of Sundance Institute |

We realised we had to protect the identity of some people for different reasons but in the three cases that we’re doing that, we’re being very clear about the artifice.

How did you get Emma Thompson on board as an executive producer?

FBS: It was just a matter of asking her. It was clear from the very start that this would be a difficult film to fund in the current climate. We had a connection through Nae Pasaran. It was basically through a collaborator on Nae Pasaran that we sent her a link to the film and she replied very quickly – a beautiful letter and she helped a little bit with the promotion of the film then. So we’ve been having conversations since then. So I just reached out and said this is the thing that we’re working on and within days she replied very positively.

How was it to work with actors in this film for certain segments, because usually as a documentarian you are reacting to what happens rather than directing it?

FBS: It was quite liberating in a way. We still had to go through the process of interviewing everyone and creating transcripts and then using those transcripts for a kind of set design. There's this fine line between safeguarding and protecting people's identity but also you want to convey a sense of their personalities and so there was something quite creative about having that process. With Scottish protest, from the research I’ve been doing for the last decade, there’s a beautiful balance of a great sense of humour and tenacity and a sort of taking no shit attitude – so it was important to have actors who could convey that.

Everybody To Kenmure Street will premiere at Sundance Film Festival on January 22. It will open Glasgow Film Festival on February 25.