Eye For Film >> Movies >> Duel (1971) Film Review

Duel

Reviewed by: Andrew Robertson

Duel is often described as Steven Spielberg's first film, and though that's not wrong it's also not the whole story. Indeed the version we see now is more than the whole story. What was filmed as an ABC television movie had additional scenes added to extend it for a theatrical and international release. That version starts with an opening sequence which makes a virtue of simplicity.

We are on the move. Streets that become progressively less trafficked, the radio less certain, the hills more prominent, the spaces between other vehicles larger and longer. More and more of out there, less and less of others, until it's near enough one man and the open road. That's Dennis Weaver, to some audiences more famous for this than anything else. A veteran of the small screen, he'd spent nearly a decade in Western series Gunsmoke, but in and among single appearances in other serials he'd done a few TV movies.

Spielberg hadn't done even that. He had directed the very first episode of Columbo, a couple of other bits and bobs. He'd been pointed at Richard Matheson's short story, published as was the style at the time in Playboy. The old joke about reading it for the articles hides how much money Hefner had for long-form journalism and fiction commissions. As with the lingerie, the contents were more substantial than padding. Matheson's short story joins a weird list that includes works like The Fly, nearly as frequently adapted as his own I Am Legend.

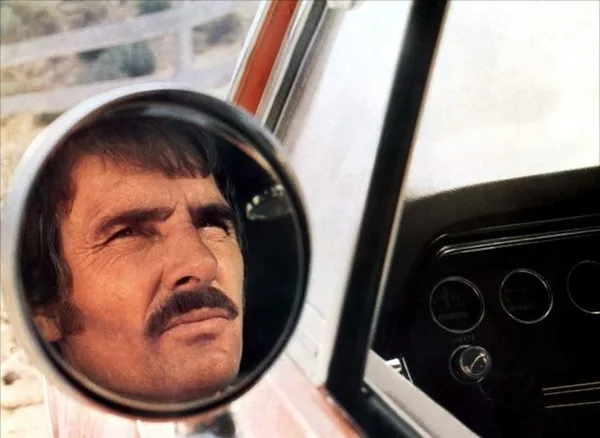

Matheson adapted his own short story too, but through silence and voice-over it's Weaver's performance that makes his David an everyman. It's 1971 and the oil crisis isn't even on the horizon. What's looming instead is a tanker, a Peterbilt rig that's harbinger of all sorts of things to come. Peer closely and you'll see that sometimes it's a 281 and at others a modified 351, because Spielberg's first film was also his first revisitation. Those extra scenes would require a fair bit of invention, and not everything could be done with a washing machine door and a bit of awkward stance.

Those two bits of framing join dozens, scores of others. It's soundtracked by Billy Goldenberg, and it's hard not to try to compare it to John Williams' later work with Spielberg, but it's compelling in a different way. Orchestral strings can readily make puppets of audiences, and their skirl and stabs are more than enough to hang from. Despite its quality it's overshadowed by the camerawork. A tight shooting schedule meant that the young director was paired with several veterans. That included cinematographer Jack Marta. His earliest credits were from 1926 so by this point he'd been working 45 years. Those who've seen The Fabelmans will be watching the horizons, and might be interested to note that Marta worked on the same film as John Ford only once, on 1926's What Price Glory.

That sense of history, film-making and otherwise, is one of Duel's attractions, but it more than stands as a film itself. In that long sequence at the start we get further and further out of civilisation, communicated with lightening traffic, radio cutting out and changing, fewer and fewer cars, clearer and clearer skies. It's a brilliant sequence, the camera in the car and the road close, the tarmac near and the hills far and all of it boundless and boundary. It's a remarkably efficient film, and many of the DVD versions include information on the making of it that make clear just how much so. It was was shot in about a fortnight, the additional scenes for the re-release in a few more days. The use of a camera car custom built for Bullit isn't the only place where there are borrowings, but Duel was inspiration to so much more.

Ignore the bits that Spielberg will reprise himself. Watch and consider that line from Mad Max, "perhaps it's the result of an anxiety." This is a new starting point in a relentless pursuit. In it are things that will become hallmarks of Spielberg's work, moments that would inspire countless other filmmakers. There's a story that George Lucas went upstairs at a party to watch it, that he came down during a commercial break to tell Francis Ford Coppola he should make his excuses and come and see it too. With the benefit of hindsight there are things that you'll quite possibly have seen before, but here, for many, they were seen first.

There's a confidence to it all. Even the uncertainties: the truck's countenance is baleful to some, a friendly face to others. Weaver's performance is the most significant. It's not a one-man show but in the episodic progress of the duel itself it's his face and Spielberg's framing that are fighting to keep you most involved.

The voiceover does feel a little dated, but that might be me back-projecting from issues with versions of Blade Runner. Other conversations with those Mann meets along the way do more than the internal monologue. More than those, though, the presence of the truck. WM3227 is its license plate, but it bears others on its front bumper. Confusion becomes concern. As the pursuit continues, what at first seemed trinkets start to resemble trophies.

Spoiler warnings for a film more than 50 years old might be redundant, but on a re-watch, even knowing what comes next, I was caught up. I could not tell you when I first saw Duel. I couldn't be certain which version I saw first either, but I'm not sure it matters. In 4:3 it's got a particular claustrophobia and in one of many treats in wider screens you can try to spot young Steven in the back seat.

The road that Duel follows has plenty of stops: the gas station, Chuck's café, the snake farm, the school bus, but those rolling hills across the empty desert are differently a landmark. Duel is born from a propulsive and haunting short story, "At 11:32 a.m., Mann passed the truck" remains one of the great opening lines. Spielberg would catch a whopper with another, "The great fish moved silently through the night water, propelled by short sweeps of its crescent tail," but this was what set the hook for that.

That truck is in its own way a monster, it doesn't breathe quite like the war rig but it circles and feints like any number of predators. It remains a bit of movie magic. What was then novelty is now history, but no less powerful for it. It retains a sense of speed that's rarely been matched. The lens flare that was an artefact of rapid production is now a form of verification. Even videogames borrow it to seem more real. The pace includes the editing. It seems absurd to suggest that moving from speedometer to temperature gauge and back might be suspenseful but between the cuts and those needles and the score the audience's blood pressure is as tightly engineered as the vehicle's oil.

As an indicator of talent the film did more than blink. This wasn't just signal but a proper starting gun for a filmmaker whose multi-faceted oeuvre owes a huge amount to what started as a horror story in a men's magazine. Duel is a gem, and while not exactly buried it will still reward anyone who chases it down.

Reviewed on: 20 Jan 2026