Eye For Film >> Movies >> Bad Hostage (2024) Film Review

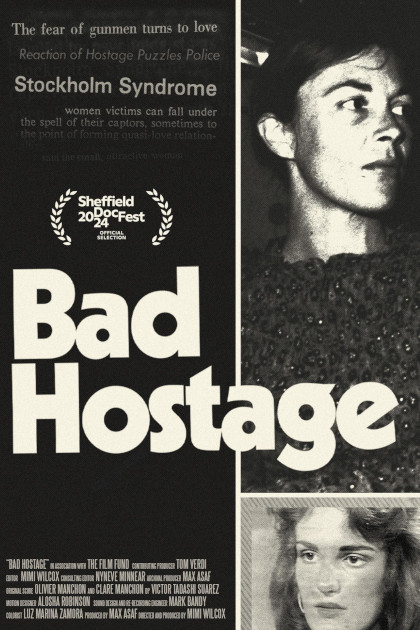

Bad Hostage

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

The history of psychiatry in the Twentieth Century is full of strange ideas; the history of pop psychology even more so; yet few have gripped the public imagination quite like Stockholm syndrome. It proffers, after all, an insight into the mysteries of the female mind, giving therapists and, more commonly, media outlets a go-to explanation when female hostages don’t behave the way they are supposed to. Why do these unfortunate damsels sometimes seem ungrateful towards their heroic rescuers? Why do they show sympathy or even friendliness towards their captors, and why do they claim to feel afraid of the police? The answer must be that they have fallen in love with their captors.

Stockholm syndrome has never been included in the Diasgnostic and Statistical Manual on which most modern psychiatry hinges, and there is little to substantiate it in academic literature, yet it has remained popular for over 50 years, leading to the ridicule of a number of women who emerged from dangerous situations. After all, what else could explain their behaviour? They couldn’t have been trying to survive, could they?

Michaela Madden came to public attention in 1973 when she and her five children were held hostage in their rural home near Sebastopol, California. Their captors were fugitives from an earlier incident in the town and, as she saw it, young men who had made bad decisions. Her calmness and quiet reason were a major factor in bringing the situation to a peaceful end, with nobody getting killed – but her complaints about the police handling of the situation led to her bring monstered in the press. Again, she was patient and it blew over, become a family story with an unexpected, hilarious punchline. Now her granddaughter, Mimi Wilcox, has used it as the foundation of this Oscar-shortlisted documentary.

Wilcox’s interest is in exposing the popular myth about women’s behaviour for what it is. To do so, she draws on Michaela’s experience and compares it with two well known cases: the kidnapping and supposed brainwashing of heiress Patti Hearst, and the bank robbery turned hostage situation which inspired the invention of the Stockholm syndrome theory in the first place. All three of these incidents took place within a two year period and although her film is only 39 minutes long, Wilcox has a lot to say about them. She draws on newspaper clippings from the time, and archive interviews which bring the women’s voices to the fore. Michaela speaks directly. Amongst her memories, as clear as if it were yesterday, hearing the police say that they were going to catch those fugitives at any cost – a position quite at odds with her desire to keep herself and her children alive.

In amongst this footage are some extraordinary comments from Truman Capote, appearing on a chat show, which just scream projection and will make you reassess his celebrated perceptiveness. Rather than a simple condemnation of the attitudes of the past, however, the film is a plea for people to reexamine their attitudes in the present, in relation to this subject and other areas of received wisdom. It’s an argument for the application of reason, and a plea for women who find themselves taken hostage to be given the courtesy of being seen as human beings who might quite reasonably try to protect themselves. Thorough and forthright, with a measure of wry humour, it’s a powerful piece of work.

Reviewed on: 18 Jan 2026