|

| Redoubt |

One of the triumphs of John Skoog’s second feature, and first fiction full-length, Redoubt, is that it is constructed around a literal construction – a building that was created over 30 years by Swede Karl-Göran Persson, who became obsessed with making a place to protect himself and his small community in the event of war. Persson was inspired to fortify his home after reading a government pamphlet If The War Comes, offering instructions on what to do in the event of an enemy attack. The film version sees French star Denis Lavant perfectly cast as Persson, begging and buying all the scrap he could before adding it to his incongruous fortress, and becoming something of a local legend in the process.

The film, which is gorgeously shot in black and white on 35mm, had its world première at San Sebastian Film Festival in the New Directors section and will screen at London Film Festival next month.

|

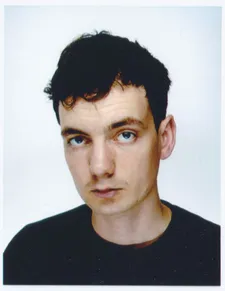

| John Skoog: '“I must say I was fascinated with this character as a child, maybe in a little bit of a different way' |

Redoubt began life as a short film art installation in 2014 and Skoog says, when we catch up with him in San Sebastian that he always knew he was going to build the place.

“I think the best way to kind of talk about it was that first we had to try to find a place where it fitted and then me and my brother, who I work with very closely, found this place that is very close to where we grew up, on our cousins’ land. Then we started working together with this production design, Søren Schwarzberg, who has done a lot of big Danish costume dramas and period pieces and so on and when he had read the script and started looking at the material I sent him, he was like, ‘How do you make a plan for building a house that is made without a plan? How does that work? So that was one question.”

Although the final building is not an exact copy of Persson’s redoubt, it was “very inspired by it”.

Skoog explains: “ I would call it a reconstruction. Then you’re back to this question of how do you make a plan and recreate something that was made without a plan? Instead, my brother and Søren put together this crew of artists and local craftsmen and people who were used to working with plaster and wood and so on but not the normal kind of set builders.

“The set builders only made the skeleton of the house. Then fewer people worked for a long time trying different things. They said, “Now we go back to our studio” so they were down there, trying different things and testing, looking, discussing then working a little bit more and going back looking so that somehow it was allowed to grow a bit organically.

“Then Viktor Lindström, who was the prop master, really became like Karl-Göran and drove around all of southern Sweden collecting all types of junk he could find in any barn. Every day he came with a pickup truck full of junk that they had as material to work with. So he was very like Karl-Göran and one thing we realised when we were working on it was that it took Karl-Göran from the age of 47 to 75 when he passed.

“To be able to do all this by yourself is crazy. It's almost impossible just to mix that amount of concrete by hand. Also one of the very beautiful stories that drew me to this was he didn't have a driver's licence so everything he wanted he had to take either by carrying it or on his bike. He didn’t have any building permits but the region didn't know how to stop him so they just tried to tell people, “Please don't give him things and definitely don't sell him anything” – they told all the hardware stores and so on. So he had to bike further and further away to get his stuff and that’s what happens in the film.

“As you see in the film, when he gets his pension it was the first time he could order enough to get it delivered, so that was a very big moment. I think he saw it as confirmation that the state supported this project.”

It was a tough ask for the crew on the set, given that a lot of physical lifting was involved, with Skoog noting they put “every last ounce of sweat and blood into it”.

He adds: “Viktor, the prop master, kept going through the shoot but he had all these assistants who kept dropping out. So he was like a mad legion leader who kept going as everyone else fell. But if you dare to have this open process it also gives you a lot of flexibility.”

One thing he admits he didn’t foresee was the way that the craftsman had no experience of being on film sets so didn’t realise what having a film crew tramping in would mean.

“When a film crew comes in it’s kind of like an insect swarm, it destroys everything.” Skoog says. “They had been taking so much care of this place and keeping it pristine and then along came the lighting guys and that change was hard for them.”

It needed a masterclass in scheduling as well, because of the back and forth between shooting within the house and the construction but they had six weeks in summer and two in winter to complete the film and the artists who constructed the set prepared elements in advance so they could be added more quickly.

“I think the house is like a main character in the film,” says Skoog “And we also discussed in the editing this thing of “How do you feel that it's growing? Where is he actually building?” Yesterday was the first time I saw it with an audience that wasn't going to give feedback, but just experience it, which is a whole different thing. And I somehow realised, now over the last few weeks, that it's really growing in this strange way, that it’s his obsession taking over. It's not going up like a high rise with first floor one, then floor two, but it's growing in strange ways and you just feel the walls getting thicker somehow. So that's really a good thing.”

Lavant also has to be something of a master craftsman when it comes to building his character, taking on Swedish for the dialogue but also physically carrying things and working on the house and turning his hand to farm work.

“I think it’s a while since he did a film that was so physical and for such a long time,” says Skoog “He wanted to live as close to the set as possible and his only demand was to have a bathtub so he could let his body rest in hot water after the day. The film deals with loneliness but Denis was also a little bit alone because there’s usually many other actors but the others came for a day or two but he was still more like an alien or a foreigner – the French movie star with all these all these people that actually live in the village. He became a little bit like Karl-Göran, biking around in this little village.”

The children of the community seem to be more on the same wave-length as Persson than the adults and that tension between the different viewpoints of him came via Skoog’s research, with his interest in the building stemming from what he learned about it as a youngster.

“I must say I was fascinated with this character as a child, maybe in a little bit of a different way. It was not explicit back then, but if I had to put words to it now, I’d say this thing of deciding to live your life how you want instead of following a path – I’ve always been drawn to stories like that.”

Talking about the evolution of the film, Skoog says: “The film comes from a short film I did for the Towner Eastbourne gallery in southern England, then it travelled to different museums. I conducted a lot of interviews around Karl-Göran with people who have met him or lived close to him or so on. And of course since he died in 1975, most people I met had childhood memories of him.

“Then I also found that the year after he died, there was a local journalist who interviewed a lot of people about him collecting stories in 1976. That included the police officer in the town, the people he worked for, his contemporaries in a different way, who remembered him not as something in the past but something very ‘now’. These two views on the man, both were so different. There were things that were aligning, like his strong singing voice, his strength, and his kindness and his determination. But the ones from back then also didn’t understand why you would do something like that.

“My interviews with the children saw him more like a legend and that’s something we thought would be an interesting tension in the film. We thought the children were a good way to enter his world. So at one point in the film you’re just with Karl-Göran and aligned with him and the children were a good entry way to him in that way. Their view of him and how they were slowly getting into his world view, so starting to say, “The war is coming”.

That phrase, in particular, strikes a fresh resonance today, with news of conflicts around the world and drone incursions in Europe.

“This thing with the current political situation is, of course, even more complicated because when we started talking about it, it was already also that we live close to end times in a kind of ecological natural world way.

“The militarisation of Europe. Germany now suddenly investing amounts of money they were not allowed to invest in weapons, until very recently. I read just a few days ago that Europe has spent more on weapons this year than in any year since 1987. When the natural world has completely fallen apart, what are we going to do with all these guns? It's also funny with these populist right-wing governments who are complaining about how expensive culture is and Swedish film funding is not even 0.1 percent compared with what they're spending on weapons. It's not a placard movie but it's inviting the audience to look at these kinds of questions together.”

The film also shows a shift in the world that Karl-Göran inhabits too, the disappearance of day labouring with mechanisation, for example.

“I think that's a really important thing in his life, in his story, but also for the film. It’s like a background for the film. What’s really interesting about the real house is that it’s almost like a museum in a way because he took everything he could get for free – and that was all these old things. Everyone got cars so no one needed their bikes, everyone got bigger tractors, so they don't need their small farming tools and all of those things are now in the concrete, in the real building.”

The building is now going on to have a second life as an art exhibition in Sweden, so that the project has sort of come full circle. But Skoog is looking forward to more fiction work in the future. “Fiction film is a really special expression,” he says, “It’s the most beautiful. I really like that it’s such a long work and you can spend a lot of time thinking about one thing and I also like the collaboration. It’s the best.”

- Read what Denis Lavant told us about crafting his character