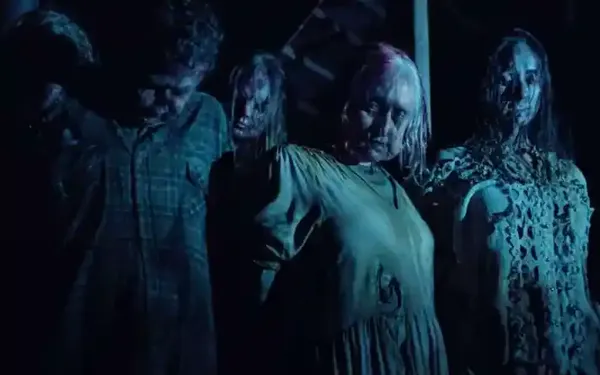

As the retrieval begins, it's discovered that some of the dead are starting to show signs of life, and lash out violently. Ava, however, has an ulterior motive for volunteering – she's searching for her missing husband Mitch. Assigned to the northern part of the island, when she meets Clay (Brenton Thwaites), another volunteer, the pair abandon their unit and set off south in search of Mitch.

Hilditch has previously directed the apocalyptic thriller These Final Hours, as well as the adaptation of Stephen King's novella 1922. He also directed Rattlesnake, a dark tale about a mother having to repay a stranger's good deeds in unimaginable ways.

In conversation with Eye For Film, Hilditch discussed becoming entrenched in genre cinema, but with hopes of making films outside the genre. He also reflected on the moral murkiness of his zombie survival horror, the primal sound design, and not directing the last ever film.

The following has been edited for clarity.

Paul Risker: How would you describe your relationship to cinema?

|

| Zak Hilditch: 'I thank the Lord I was born in 1980, and that my hobby of wanting to be a filmmaker turned into a career' Photo: Courtesy of SXSW |

My mom was a massive cinephile, and so, my sister and I spent a lot of time at the video shop, and staying up late watching things that kids shouldn't be watching at all. And all that has been stored away somewhere in my brain. I'm sure a lot of kids have that same experience, but it doesn't then lead to filmmaking. I'm really lucky it somehow did for me.

I sort of forced the issue because I couldn't do anything else – it's all I wanted to do. But yeah, looking back, you don't realise the osmosis effect of renting horror movie after horror movie and staying up late and watching Alfred Hitchcock Presents or The Twilight Zone.

PR: Do you think films not being on tap for previous generations forged a deeper communion with cinema compared to today's?

ZH: Yes, and you were just so much more willing to put pants on and go down to your local cinema and see the thing, rather than waiting a month or two later and watching it on the couch with your pants off. You had to physically drive to the video shop or physically go and watch the film, or you were left out of the conversation. Or the film was gone, and you wouldn't know when it was going to be released on DVD. So, the stakes were higher.

The video shop was great and just being physically there, you'd be thinking, "Have I made the right choice? I've got a buck seven, but how am I going to get another film?" It was just such a different way of looking at cinema and valuing each film.

PR: Did you always have a sense that your future was in genre cinema?

ZH: I honesty didn't know. Outside the films that I've made, there have been many left in the graveyard that were supposed to be the next one that weren't so uniquely genre-centric. I guess there's been a little bit of genre in the ones that are dead, but some of them are just straight dramas as well. The ones that have gone onto be made are the ones that do have that big genre element, and I guess that's just the marketplace. They're all my babies, but some are heartbreakers left along the way.

I love stories about ordinary people caught in extraordinary situations. I have a love of kitchen sink drama and intimate indie cinema smashed together against the big backdrop of some event. I love the juxtaposition of those two things and how you can have your cake and eat it too. And ultimately, that's where the best genre movies lie. The ones that just so happen to be unfolding against that big event, but it's actually a character study or something else. You get really interesting one-of-a-kind experiences that way, and that's the sort of work I have been doing. We Bury The Dead, is that in spades.

PR: We Bury The Dead is a journey where what the characters and audience think they know, continually expands. However, this is not done through big twists. Instead, it feels more like a natural transformation.

ZH: It's unfolding, and ultimately, it's being true to the world and what Ava's trying to achieve. And how she gets there is what excites me. It's the rug pulls, it's the left-handed turns within the zombie framework where you're like, how is this now a Hitchcockian thriller in a candlelit ye olde homestead? What's going on? As long as I was always being truthful to her journey and allowing her to bump into other characters that are also experiencing their own grief because of this event, I thought I was really onto something.

PR: The film cannot be described as either being optimistic nor cynical. Instead, it's a mix of the two as the characters march onwards.

ZH: Oh, 100% and just from a simplicity point of view, the invention of Clay being the yin to Ava's yang. And he allowed me to have those Aussie larkinisms with the unexpected things that come out of his mouth.

Writing We Bury The Dead, it was about who's the most unlikely person that she would be paired with? You don't want it to be someone like her. You want it to be the complete antithesis of everything she's about. And that's where worlds collide and conflict equals drama. And you also get to have some dark humour as well, because she's already a stranger in a strange land, and then she meets this guy. I just love road movies about unlikely pairings, and so, I was exploiting that as much as I possibly could within the film.

PR: Your film has traits of both Richard Matheson's I Am Legend and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, in the sense that the role of the monstrous can be flipped. Human beings can be the monstrous and the creatures can be the ones that deserve our compassion. In Bury The Dead you appear to enjoy blurring these distinctions.

ZH: The character of Riley, played by Mark Coles Smith, could have had his own movie – this could have even been his movie. We're following a guy who's making interesting yet not very healthy decisions because he's completely grief-stricken. If I was in his situation, what would I be capable of? And it was my job to look at it from that point of view. It just so happens that when we do meet him, it's not his movie, it's Ava's. And he then makes some really interestingly bad decisions which I won't spoil. So, he became the "baddie", but was he?

I love that murkiness where no one's good or bad. It's real and honest because he's going through the stages of grief, and we just meet him at his most heightened version, and things escalate very quickly. And then, with the zombies, we think we know what they're about. But then we start to realise that we don't know everything about them when we meet one in particular one.

If you're going to make a zombie movie in the modern era, you better have something new or unique or at least try to do something that adds something new to the conversation. You need to honour the audience's expectations and yet find ways to then pivot in an interesting and unique way that makes the story feel real and visceral and hopefully not a letdown. But this film is exciting because you don't know what's about to happen, and you haven't seen something quite like this in a zombie film before.

PR: One of the striking aspects of this film is the sound design, specifically the sound of grinding teeth. It's a naturally unnerving, even primal sound that I'd liken to nails along the blackboard.

ZH: The whole teeth thing grew out of trying to make our zombies unique, without having any money. So, it was about how we can be interesting, and people do underestimate sound, which is so important.

Riley says, the longer they go on, the more agitated they become, so, from a script level, I was playing around with the idea of what would that sound like? That sounds like teeth grinding because you're growing more and more agitated as you realise, 'Wait a minute. I'm not whole; I'm the living dead. This isn't good.' Wherever I could play with that idea, I absolutely relished it because it's this primal thing.

|

| Zak Hilditch on filmmaking: 'When you finally wrap the film, it's a relief' Photo: Signature Entertainment |

PR: Is the making of a film a transformative experience?

ZH: Oh, absolutely. To make a film, from having the initial idea sitting alone in your underwear at your laptop and opening up Final Draft and fucking around, to then releasing the film, what you have to go through, it's so hard. And it's an absolute miracle. Even when we were making the movie, I was saying to the producers, "How can movies be this hard? How does anyone do this? Is this the last one? Am I the guy that makes the last film?"

What you ultimately experience with the ending is relief. You're not elated, you're not excited, it's a relief that you think you got it all, and now you can just fuck off with your editor into a dark room. And that's a different kind of stress that's around the corner, but at least it doesn't involve the circus, and you don't have to be the frontman any more, which I'm fine with. That stuff's actually very easy for me, but it takes a lot out of you and, day-to-day, you're relieved that you got through each one.

So, when you finally wrap the film, it's a relief; you can't believe that you got it all. And now comes the question whether it is good, is it bad or is it mediocre? You're about to find out, but at least you got it all, and you won't ever be as relieved as that.

When you make a film, and it turns out pretty good or okay, then that's another win as well. If people aren't spitting on you in the street, that's a bit of relief in itself [laughs].

But you do feel different, and each one does change you because you learn so much from one to the other, and, unfortunately, in my situation, I have never gone immediately onto the next one. There's always been a hiatus and hopefully there won't be as long a gap between this and the next one. But it would be awesome to finally go from one to the other. So, we'll see, but they're all just minor miracles.

We Bury the Dead is available on Digital HD now and on Blu-ray and DVD 16 February. Distributed by Signature Entertainment