|

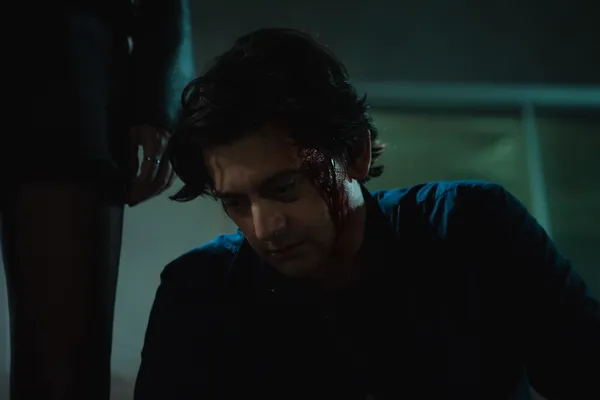

| Josh Fadem as Joe in Every Heavy Thing |

“I wasn't as confident with this one because I was doing something different,” says Mickey Reece. “Essentially, if it didn't have style, it would just be a normal movie.”

If there’s one thing Mickey can’t be accused of, it’s making normal movies. I have, however, described Every Heavy Thing as his most accessible work to date, so I take a moment to reassure him that I don’t mean that in a bad way. It’s the story of a man who witnesses a murder and is then threatened by the tech magnate responsible, causing him to stay silent and gradually crumble under the resulting moral and psychological pressure. It has been warmly received at festivals, but he didn’t take that for granted.

“Going into it, I was just like, ‘Man, I didn't do enough for this one,’ he says. ‘I didn't go into it enough. So even adding some montages and all the glitch stuff make me think ‘Alright, I'm doing something with this, as opposed to just making a standard paint by numbers thriller.’ But that's kind of how I went into it, not so confident before it came out, because it seemed so normal to me. Then the reception came and I was just like, ‘Okay, yeah, we did something good here.’”

I tell him that I would have recognised it as his work anywhere. He tends to take an interest in a subgenre and then repeatedly distil the associated imagery into something really powerful. Here it’s the essence of a Seventies thriller.

“I try to do that with all the movies,” he says. “Like, create a normal movie, but then do things to it. But in the past, they've always ended up completely not normal. Script-wise, going in, the films always change enough. With this I wasn't as confident because I had to do like crazy things to the narrative.

“I feel like a lot of movies are formulaic. As much as they're going to probably promise something different, it always seems to be the same thing. It's like the audience and the marketing already have an agreement before anybody steps into the theatre. You know what I mean? It almost gets to a point where you're trained to either write this way or structure something this way, and it's hard to go off of that because you're like ‘Well, this doesn't work.’ It’s like good taste or bad taste is just based upon familiarity.”

Characters also tend to behave in formulaic ways, I suggest. In most films, a scenario like this would prompt the protagonist to do something bold and heroic or become an amateur detective, whereas here, he behaves more like real people do when they’re frightened and overwhelmed.

He shrugs. “Anytime I hear the word ‘real’, I think ‘This is not realistic in the slightest. Not at all.’ But yeah, you're saying that it taps into something, like working out the story in such an indirect way makes it more real. Like, the process of the story is more real in that you're engaging with it differently than you would just a normal formula movie.”

It's about a human experience as opposed to a sort of dramatic experience, I venture.

“Yeah, I can get behind that. You know, a lot of people always say, in acting and stuff, that they're searching for truth, and I'm never searching for truth. You know what I mean? I don't know what I'm searching for, but it's never ‘I want to make it like real life.’ I want to make it so far beyond real life. Even if it's just a normal two characters in a drama, I still want to make it something almost fantastical in their approach to what they're dealing with.”

I note that he’s good at finding the absurdity in situations like that, and creating comedy out of it.

“Well, you know, I think when critics say stuff like ‘Expect the unexpected with Mickey Reece’ – well, not really. You can always expect it to be funny. The jokes are not written in the script, but when we get there on the day and I see a dynamic with characters that is something funny, I'm always going to lean into that, for the good or the bad of the film. You know what I mean? Even if it's in detriment to the film, I'm still going to be like, ‘but this is funny. Let's play this out. Let's see what happens with these characters doing this.’

“It's definitely gotten the point of actors being into their character and then like, ‘Oh, wait – you want us to play it like this now?' Almost like it's undermining it by being humorous. But I'm like, ‘I can't help it. We're here. Let's have a good time. Let's make it happen.’ And I feel like ultimately it's about having fun when you're in that situation. It's very tense on a set and everything. And yeah, if there's some levity to be found, that. And we're going to find it, and we're going to use it to our advantage.”

Although his films are always high quality, he’s incredibly prolific, which would seem to be impossible without having fun, I suggest, and he agrees.

“You know, between Country Gold and Every Heavy Thing is the longest I've ever gone without making a movie. And that's because we had another movie called The Cool Tenor that were trying to get off the ground, and I learned what it's like to work with big studios. Not studios, but, like, bigger fish, and work with bigger actors and get it all aligned. And I'm just like, ‘This is going to take forever at this rate. I just want to make something that we can make.’ I still want to work that muscle. And just sitting at a computer all day talking to people about making a movie is not working that muscle to me. So we put that on the back burner. It was going to take longer than I wanted it to, and I was like, ‘I'm going to write something that I know I can get financed and we can get going.’ And that was everything.”

Is he still intending to do something with that project?

“I would love to, but I'm just not patient enough. I'm not in that place to sit there for a few years developing a project.”

I tell him that part of what I find interesting about Every Heavy Thing is that it manages to keep its film noir intensity despite the comedy, and the way the comedy just sort of blends into that styling and makes it more powerful in a way.

“I like that take on it,” he says. “It feels intuitive. It always feels natural when we're doing whatever we're doing. It's just like, this is just the way it went. I'm sorry that it was like this in the script and ended up like this, but this is just the way we felt like going with it, and it just felt right, you know what I mean? Also, I'm working with a lot of comedy actors, and they're kind of being restrained. I feel like if were just going by the script, the way the words read, and not adding more humour, well, then I'm not really using these actors to my advantage – these particular actors that have these particular skills that lean more towards comedy.”

I mention that I have a stand-up comic friend who said to me once that stand up comedy is often perceived as being about aggression and power. It feels like some of the characters in his films are more powerful because there's that sense of comedy. It suggests that they've got more control of the situation than the average character.

“Yeah, that's interesting. Because I feel like the protagonist, Joe, is very reluctant to be a part of the entire story. His whole thing is ‘I didn't want to do this. This isn't what I had in mind. I was comfortable,’ you know? It might be like an immaturity thing. There's just no other way to deal with these things going on other than making a silly remark about it or being sarcastic about it, just to put the audience in it. That's just like, ‘I don't even want to be here, alright? This is not like something I ever wanted to be a part of. So now I’ve got to keep all these secrets and do all these things and have this whole thing happen in my life.’

“It's how I would behave if I was in that situation, if I had seen somebody kill somebody. And then he [the killer] is like ‘Alright, so we're going to do an experiment. I'm going to stay with you and haunt your dreams and stuff.’ And then I'd be like, ‘Man, I didn't necessarily want all this.’ You know, it would manifest itself into jokes.”

We talk about those dreams, and the amazing Eighties graphics they feature.

“So when we shot it, I was just like, ‘We're going to shoot some stuff on a green screen and I'll figure out what to do with it later.’ I started editing the dream stuff and then Peter Kuplowsky, the producer, said he ‘I’ve got this guy that does glitch stuff. What do you think about doing VHS glitch stuff? Like, real analogue glitching.’ And I was just like, ‘I don't think so. I think that's just going to look like crap.’ And then his friend dis some stuff and I looked at it. He would send me five different versions of it, and then I would pick out the little glitches. And I was like, ‘Oh, okay, this works.’

“I think that's what they were coming at me with from the beginning, but I was like, ‘I don't really understand how this works.’ And so I figured it out on my own, how to work in the glitching, and I was like, ‘I really like this. Give me more. Give me more.’

“There's this digital looking map. In the very first dream sequence you're flying through it and it has all these lines and stuff and it looks very like Tron or Freejack. Very, very Eighties, from that era’s style of CGI, I guess. There was a short documentary we saw at Fantastic Fest one year, that was a guy filming through the camera of a Tesla. It gives you these weird little digital designs of moving through bridges or little tunnels. And so I was like, ‘Well, we need that stuff.’ I got that stuff. I put that on there and then all of it came together. I'm just like, ‘This is the aesthetic of the film. This is a techno thriller.’

“It is essentially a look at technology. I wrote another script since this movie that also has technology themes. This is going to be my technology trilogy. You know, kind of like Climate Of The Hunter, Agnes and Strike, Dear Mistress, And Cure His Heart were all these female-centric or off-brand or off-culture horror movies, and it was kind of a trilogy and I'm done with that. And you know, Country Gold is going to be part of a trilogy that is a reimagining of celebrity, like a surreal celebrity world. I think right now I'm in Technology World. I mean, I'm in that technology phase that mirrors where we're at in society as far as technology goes, so I think this is the beginning of a technology thriller trilogy.

“The movie that I'm working on now is called She Needs Me. It's based on a true story about this girl on OnlyFans. This guy starts stalking her and lives inside her attic. And she presses charges, obviously. And then when they go to court, they find out that she was actually sleeping with him. The case unravels to a degree that everybody's like, ‘Well, now we don't really know what to think,’ because this is all very nuanced.”

It’s based on real events, he explains. “It has a lot to do with the Internet and people's behaviours and what's right and not right.”

There are psychological elements in Every Heavy Thing which make us wonder if what we're seeing is real.

“Yeah, and that's kind of a crutch that I had. I've noticed that the unreliable narrator is always a crutch for me, like, ‘Oh, this is how we can incorporate some surrealist imagery in all this.’ And I think one thing about the new script is that it is very much based in reality. There is nothing crazy going on. The reality is crazy enough.”

There's one other thing that really stands out in Every Heavy Thing, and it’s the extraordinary performance by Barbara Crampton.

“She was supposed to be in a green dress, with red hair,” he explains. “In the final hours, she wanted to wear this blue dress. And I immediately thought ‘It's going to look like Blue Velvet, but whatever. ‘All right, let's do it.’ And we did it. So the blue dress is what really made it look like that, but essentially, it was just a scene where there's a lounge singer.

“I obviously grew up with David Lynch movies, but he's something that's more in my subconscious rather than ever thinking about, when I'm making a movie, throwing in a David Lynch reference or something. If I do that, it just happens. But, I mean, it happens probably for a reason. When I was, like, in my early twenties, that's all I did: consume Lynch. He was everything. But not so much anymore. I'm 43 now, so now all that stuff's still in there, but I don't mean to bring it to any attention. I'm not upset about people calling it Lynch. You know me. That's fine. What could I be upset about? That's cool, you know – but it's not purposeful.

“Barbara was supposed to be in Agnes, and that didn't work out. And then when I went to do this, I was like, ‘Aright, time to call Barbara.’ And so I gave her the script, and I said ‘You can play Whitney Bluewill or Bev, who is Joe's mom. And she chose Whitney Bluewill. So it just ended up that way more so than it was designed.”

When it comes to the design of the film, he smiles and says “I mean, just straight up, we were making a Brian De Palma movie.”

That was actually what stood out to me, I say, so I'm glad he said that.

“Yeah, yeah. We're not going in to make little references to Brian De Palma movies or anything. It's just like we're making a Brian De Palma movie from memory. No one needs to go back and watch a Brian De Palma movie, we just need to be on set and then think, like, ‘Oh yeah, maybe we’ll do a split diopter shot here. Maybe we’ll put the camera down a little bit here. Maybe we have the camera go like this.’” He gestures. “Because we're thinking in the world of if were making a Brian De Palma movie, but by memory, not necessarily through direct reference.”

He’s happy that, despite his misgivings, the film seems to be a hit with audiences.

“We have had pretty great reactions overall. That has made me reassess the movie, now that I'm not so attached to it, go back and see what it is and look at it for what it is. I understand why audiences are liking this one more than some of the others, because it's challenging in the right ways, but not challenging in the way that it's just like, ‘Well, I don't know what to make of this.’ You know what I mean?”

It seems like it might get new people to explore some of his other films, I say.

“Yeah," he laughs. "And then they'll be upset when they see the other films.”