|

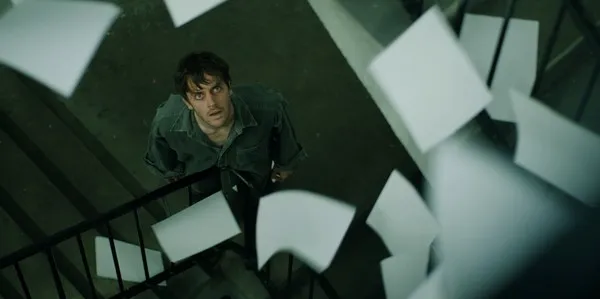

| Blockhead Photo: Frightfest |

After co-directing and producing the Grierson-nominated documentary American: The Bill Hicks Story, Matt Harlock pivots from exploring the life of the famous American comedian, to the angst of a struggling novelist. This time around, however, Harlock is in narrative territory, and yet he's tapping into genuine anxious doubts and fears.

In Blockhead, Will (Danny Horn) is struggling to complete his second novel. Worried that everything around him will disappear, including his book deal and his girlfriend, he finds a muse in the form of a drunk and psychotic decorator, Mikey (Joe Sims), who might not be real.

Harlock has previously directed the short films Toll, about a parking attendant confronting his past, The Monkey Cage, which explores the choices we make and asks whether it's possible for us to change, and Deep Clean, about a young man who makes a surprising discovery during work experience with his uncle's road crew.

In conversation with Eye For Film, Harlock discussed exploring his own inner fears, the uncertain origins of inspiration, and crafting a Jungian tale of horror.

The following has been lightly edited for clarity.

Paul Risker: A director's first narrative feature is a milestone moment. How do you look back on the experience of making Blockhead?

Matt Harlock: The main thing that filmmakers are looking to be able to prove is that, yes, you can do a short film in 10 minutes, but what people are looking for is your ability to tell a story over 80 or 90 minutes.

This was a big milestone, but I've been making shorts for quite a while — I've done eight or nine, and I've had some success. So, I felt like I was on firm ground in terms of scripting and working with the actors. The main thing I was focusing on was how to make that story work over 90 minutes, and that meant we spent a lot of time on the script.

I'm fortunate to have friends who are filmmakers and were able to give their time up to read it. I worked with some good script editors, and I also had a fantastic editor in Chris Blaine, who is a director himself. He made Nina Forever as part of the Blaine Brothers.

Chris has been a friend of mine for some time, and I was flabbergasted when he said he would come on. I didn't think he would deem me worthy or whether he would have the time. But having someone who has done that kind of thing before, and who understands the genre and what I'm trying to do, was a big part of my attempting to scale that hill.

The two of us felt comfortable working with each other. There wasn't any kind of holds barred in discussing what was going to be in and out — it was egoless. So, going from shorts to features is a big thing, but I did have help, and I feel lucky and fortunate that I've been able to work with those people to bring Blockhead to life.

PR: When I was interviewing filmmaker Sean Brosnan for My Father Die, he explained: “I know a lot of friends who pick their themes first or they’ll pick a story and then say: ‘What do I want to explore?’ I find for me that is very limiting because I just like to explore a world and its characters; to see what theme comes out of that and to let the story dictate it.” Each storyteller takes a different approach. But to speak about theme, are you attentive to specific themes from the outset or is it a journey of discovery?

MH: The thing I was interested in and what drew me to it was the idea of the darker side of the creative process. Creativity is a strong force, but that doesn't mean it's only positive. No, it can be quite dark as well, and the darkness comes from the fact that you have a lofty idea or goal: Here is the mountain I want to climb, but I'm finding it hard. What is it about me that means I can't do this? And so, that led me rather quickly to the character of [Antonio] Salieri in Amadeus, who is mentioned in this film. The idea is he's this poor guy who was not terrible by any means; he was just mediocre. But he happens to be sitting next to the greatest composer ever, and so, he's going to look at himself as being unworthy.

What drew me to the subject was the fear within myself that I was not good enough to do this work. I wouldn't say that I picked a theme. What I'm attempting to do is to be honest about something that either frightens or inspires me.

I then gave that problem to my main character and decided not to make him a screenwriter or a filmmaker because I thought it would be too on the nose. Instead, I said, "Okay, you're a novelist, and you can't write. But why can't you write?" I then started exploring reasons for that, which includes something in his backstory about being depressed because he can't face it.

Essentially, it's a story about a guy who had success a few years earlier but can't replicate it, and so, he's attempting to try and finish his new novel. He thinks he's going to lose his girlfriend, his agent and his book deal. And what happens is, in his desperation, something manifests in his world. It might be psychological, or it might be real, but I'm keen not to define that specifically. The idea is that this character comes along who goes, "Right, I'm going to be your creative inspiration. I'm going to give you a chance to get out of this horrible hole that you're in."

Everybody has their own approach, but I guess for me, it's identifying something that I feel strongly within myself. Generally, it's something that I'm afraid of or that makes me feel sick. If it makes me want to throw up, I'll probably try and write about it.

PR: You touch on the idea that instead of writing about themes, if you write about experiences, themes and ideas will naturally emerge.

MH: Filmmakers have spoken about the idea that you go with the story that occurs to you. Then the things that you want it to be infused with will present themselves and come out. But it's a very personal process, and you find yourself being umbilically drawn towards something. And it might not be a theme; it might be a bit of music.

One of the things that I was umbilically drawn to was a book called, Writing On Drugs by Sadie Plant, where she details various anecdotal, made-up or embellished instances of famous writers and their inspirational moments. Jekyll And Hyde is one where Robert Louis Stevenson, who was in bed with a bad back, was given cocaine by his wife and wrote Jekyll and Hyde in a kind of fever dream in three days. And another one which is in the film is [Samuel Taylor] Coleridge's Fragments Of A Dream, which is the subtitle of the epic poem Kubla Khan. What happened was he'd taken opium and had been given this epic poem. Then, halfway through writing it down, he lost it. He was staying at Wordsworth's house and Mrs. Wordsworth knocked on the door and asked if he wanted a cup of tea, and this poem literally disappeared. He called it the most shocking and devastating experience of his life, which is why Kubla Khan is called Fragments Of A Dream.

The thing that I was umbilically drawn to was the idea of inspiration striking you and how it sometimes feels like it doesn't come from within you, it has come from somewhere else. I wouldn't necessarily say this was a theme, it's more like a jumping off point for exploring a story. But I felt a strong connection to exploring that idea.

PR: I'm intrigued by the relationship between our internal and external selves, and how Blockhead's struggling novelist and the handyman, who becomes his inspiration, represent these opposing forces.

MH: Joe Sims, who plays Mikey, and Danny Horn, who plays Will, were thinking about what their relationship is with each other. I was hedging around it, not wanting to define it because I didn't want to say that it's definitively this and, therefore, the exploration is over. I threw it back to them and said, "What do you think?"

I've always been interested in the idea of the dark half or Jung's idea of the shadow self. So, the internal and the external world are embodied in that, which is the idea that societally, if you have to get on with people, then you subvert and submerge your darker and animalistic impulses. You can't go running around killing whoever you like; society will fall apart.

This interplay between the shadow self and the societal self comes out in films like Fight Club, The Machinist and American Psycho. Here, you're looking at the idea of the societal self, which might be the external self, and then the interior, submerged self, which is the shadow.

I showed the cast a painting called Hypnosis, by the Czechoslovakian artist Sascha Schneider, of a dark, hooded figure with light shining out its eyes. There's this other, more passive figure submitting. Joe and Danny both said, "That's the film." So, you're right, there's definitely an interplay between the internal and external, and the Jungian idea helped it to come to life for me.

PR: Having studied film theory, a disappointment is the habitual indifference towards Jung, whose writings offer us an insightful understanding of narrative themes and ideas, as well as human nature and the cinematic art form. Blockhead is an example of a film that directly draws on Jungian ideas.

MH: Well, I don't want to come off over intellectualised, but on the back of the book with all my notes and shit, I wrote a Jung quote: "The pathway to wisdom is through the portal of hell." And that became the touchstone, particularly for Danny. I think Joe was doing his own work, but Danny was like, "That's the film." And it really reminded me of [Martin] Scorsese, not that I'm comparing myself to him.

Scorsese has spoken about when he finished making Raging Bull, some woman he didn't know sent him an enamel plate which she'd painted a picture of Jake on. The legend around the side read, "Jake fought like he didn't deserve to win", and Scorsese said, "Thank God, she didn't send me that before I made the film. It so completely encapsulates the film that I probably wouldn't have made it." And so, when I found this Jung quote, I showed it to the actors and that was a moment where something was unlocked for them, where they understood the reason for and the cost of the journey.

PR: There is the cliché that pain and heartbreak can lend themselves to bursts of creativity. Returning to your earlier point, the creative process can be both joyful and dark, which echoes Jung's sentiment that life is a mix of joy and sorrow.

MH: For Will's character in Blockhead, it was about the realisation and the acknowledgment of the self. The idea of him not being able to write came out of me exploring what would stop him from writing, and the thing that I landed on was, what he had done in his past? Is there anything that he has done that would maybe explain what is currently going on? And so, that's where the backstory of him repressing something that had happened, that he couldn't deal with or didn't want to deal with because it was too icky and too disturbing, came from.

When Mikey turns up, there is this idea that it could be a joyous and creative unleashing of his animal within, but it could also be that Mikey is taking him on this journey that will lead him to self-realisation, which means fully acknowledging what he has done.

I was excited about the idea of that journey, and I like the idea of one leading the other, as well as tapping into that idea of creativity being a force. It is not necessarily good or bad, it's just a force. It could be either of those things.

Blockhead had its World Premiere at the 2025 edition of London FrightFest.