|

| Marcel Ophüls’ The Sorrow And The Pity: "“All my discoveries must occur during the shooting in order for the viewer to share my own sense of surprise.” Photo: Kino Lorber |

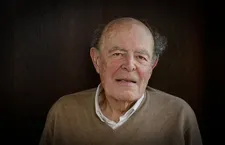

The film director who demolished one of France’s myths that the nation had always resisted the Germans and the Occupation in his documentary The Sorrow And The Pity, has died peacefully at the age of 97 at his home in the south of France.

According to his grandson Andréas-Benjamin Seyfert Marcel Ophuls died over the weekend of natural causes. He was the son of filmmaker Max Ophüls and the German actress Hilde Wall and was born on 1 November 1927 in Frankfurt.

Along with such directors as Billy Wider and Fritz Lang, the Ophüls family (Marcel later dropped the umlaut), who were Jews, escaped persecution by the Nazis by moving first to France in 1938 before fleeing across the Pyrenées to Spain eventually arriving in the United States in 1941.

|

| Marcel Ophüls, on his father Max: 'I was born under the shadow of a genius' Photo: UniFrance |

Marcel grew up in Hollywood, became a dual US-French citizen and served as a GI in Japan in 1946. When he returned to France in 1950 he started out in the film business as an assistant director on his father’s last film Lola Montès in 1955 and also worked as an assistant to directors Julien Duvivier and Anatole Litvak, and worked on John Huston's Moulin Rouge (1952). Through François Truffaut, Marcel got to direct an episode of the portmanteau film Love At Twenty (1962). Meanwhile, in 1956, he had married illustrator Regine Ackerman who survives him with their three daughters and three grandchildren.

He admitted that his father’s reputation helped him to become a feature film director, suggesting in one interview: “I was born under the shadow of a genius. I don’t have an inferiority complex – I am inferior.” Despite his misgivings one of his early films Banana Peel, a detective story made in 1963 and starring Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jeanne Moreau, turned out to be profitable even if the critics were less than enthusiastic.

He shifted his attention to documentaries. In 1967 his first foray, Munich Or Peace In Our Time, about the surrender by the British prime minister Neville Chamberlain to Hitler’s territorial claims over Czechoslovakia, received acclaim. His combination of archival footage with interviews of witnesses to the events, gave an indication of the techniques he would use to such powerful effect in The Sorrow and the Pity. He explained to one interviewer: “All my discoveries must occur during the shooting in order for the viewer to share my own sense of surprise.”

He started work in 1967 for French State television and began what would be considered his masterpiece. The course of the production did not run smoothly. He was dismissed by the broadcaster for providing sympathetic coverage of the student and workers protests in 1968. He was only able to complete The Sorrow And The Pity with the help of Swiss and German TV networks where the four-hour documentary was shown. It was banned in France until 1981 but managed to achieve some success and notoriety with screenings in some French cinemas at a time when documentaries rarely found an audience.

|

| Nazis in Paris in The Sorrow And The Pity. Marcel Ophuls: 'Who can say their nation would have behaved better in the same circumstances?' Photo: Kino Lorber |

The protagonists of the film were the ordinary citizens of Clermont-Ferrand, whom he and his colleague, André Harris, a journalist, interviewed at length. They included two farmers, brothers who fought in the Resistance; a shopkeeper who took out newspaper ads to explain that he and his family had always been Catholic despite their Jewish-sounding last name; and two schoolteachers who claimed not to remember the cases of colleagues persecuted by the Vichy regime. Even French president Charles De Gaulle remarked on the work’s “unpleasant truths,” saying that, “France does not need truths; France needs hope”.

The film ranked 11th in Sight and Sound’s best documentary poll (conducted in 2019) and restored copies recently have found their way into festivals to be appreciated anew by younger generations.

He continued in the documentary mould with A Sense Of Loss (1972) looking at the situation in Northern Ireland, and The Memory Of Justice (1973) an ambitious comparison of US policy in Vietnam and the atrocities of the Nazis. Some of his work resulted in legal wrangles, leaving him disillusioned and financially challenged and to make ends meet he turned to university lecturing.

A later documentary, Hotel Terminus; The Life And Times Of Klaus Barbie, on the Nazi war criminal known as 'the Butcher of Lyon', earned him an Oscar in 1988.

He was always looking for a challenge and in 2014 he began crowdfunding for a new film Unpleasant Truths, about the continuing Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories, to be co-directed with Israeli filmmaker Eyal Sivan, but the film ran into difficulties and was never finished.

At the 65th Berlin International Film Festival in February 2015 Ophuls received the Berlinale Camera award for his life work, a fitting tribute to a ground-breaking pioneer.