Cutting Through Rocks documents the life of Sara Shahverdi, a former midwife in rural Iran who makes a virtue of revolution beginning at home. Raised by a father who decided to teach her, as he would a son, to ride a motorbike and service it, among other things, because he was sick of only having daughters, she has long been a champion of her sisters against the family patriarchy.

|

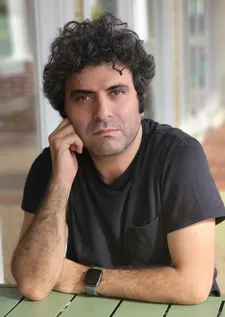

| Sara Khaki: 'I was born and raised in Iran, Tehran, and I grew up witnessing so many women like Sara in my immediate and extended family' |

As Mohammadreza Eyni and Sara Khaki’s film begins, she sets herself a wider goal – of running for office on the local council. In between campaigning, Sara also champions women’s rights, taking a particular interest in persuading teenage girls and their parents not to marry them off at a young age and going so far as to take one young woman, Feresteh, under her roof as she tries to finalise a divorce. The documentary follows her remarkable story over seven years. Cutting Through Rocks has been cutting a dash around the festivals circuit since its premiere at Sundance, where it won the International Documentary Grand Jury Prize, most recently screening at Talinn Black Nights and taking home the Audience Award at IDFA in the Netherlands. In addition to making a movie, Eyni and Khaki also formed a relationship, becoming life partners through the course of shooting it. We caught up with them to talk about the journey of the film.

How did you come across Sara and her remarkable life?

Sara Khaki: I was born and raised in Iran, Tehran, and I grew up witnessing so many women like Sara in my immediate and extended family. People who were demanding space for their lives and for the future. Then I moved to the United States at a young age and so having lived between the two worlds, I could see some of the themes that are explored in Cutting Through Rocks have some parallels here, even in the United States.

Then through extensive research, I came across Sara Shahverdi’s story. A remarkable woman who lives in the northwest of Iran, who rides a motorcycle, who had been a midwife and delivered over 400 kids, I started having phone conversations and it took me several months of phone calls until she one day shared with me that she's going to run for a council seat. That was about when I felt that there is a story here and it's worth exploring. I knew that it would be interesting if I collaborated with Mohammadreza Eyni. I’d had the chance to work with him on other projects so we understood each other's cinematic needs and language. So I called him and I said, ‘Let's go to this village together.’

Mohammadreza Eyni: I was so happy when she called me because I'm from the region, a Turkish Azeri-speaking region. Despite 30 percent of Iranian people speaking this language, it's very rare to find films coming from this region. So, for me, it was an opportunity to make a film about the community that I'm coming from.

|

| Sara and Feresteh. Mohammadreza Eyni: 'The secret sauce for getting access is being patient' |

And for me, as a male director, it was not possible to go there and make an intimate film specifically about women because of the masculine culture. So with Sara, both of us together, it was possible to make Cutting Through Rocks. Actually, when we entered the Village together, we didn't expect that we were going to spend seven years there.

Which brings me to my next question. You spent a long time making this film and, from what I can gather, over quite long periods in the village, which isn’t always the case. Were there any challenges involved in that, in terms of getting to travel there? But were there also advantages to spending several weeks at a time there in terms of the locals getting to know you?

ME: Seven years was, for us, eight sessions of filming and each session took us 90 days or 70 days or 50 days, and it was a really long time. We both decided to stay in the village to see and feel the evolution. And honestly after each session we were like, ‘This is our last session’ But with the new layers and new sub-characters, we were like, ‘No, this specific story demands more time and patience’.

SK: In terms of access, being physically there as a male/female duo of collaborators and as someone who was following Sara because of her past life as a midwife. She really knew every twist and turn of this village and had a very deep understanding of the community and the women’s communities that she was speaking with and working with, so that really had a lot to do with access. But sometimes acquiring access to certain locations like the court or the school would take us months. For example, with the court, it took us four months just to get access and we only had about 40 minutes to film in that location while there was a long line of people waiting outside.

In the meantime, we had got to know Feresteh and knew that in order for her to also get her divorce she would have to visit the judge and many sessions of court hearings before they actually filed a divorce for her. So as she was in the process, we were lucky to have about a week's window of access to film at the court, and we knew that she was assigned to go on a certain day, so we went together on the same day.

ME: The secret sauce for getting access is being patient. As a cinematographer I had a habit of going to this street talking with people and taking pictures. It was very helpful. Especially with men being in the street talking together, going to their farms and spending time with them at night with young young boys and talking with them and being closer to them and understanding them. They accepted me from day one as someone who is from the community. For women, with Sara spending time and talking with them. Many times, they invited us to their houses for dinner or lunch as a married couple.

But you did actually become life partners through the course of making this film, didn’t you?

SK: I had a return ticket back and the production wasn’t supposed to be so long but it happened so serendipitously, one thing led to another and, yes, then we ended up becoming life partners.

ME: She's so smart. She made a film, she got married and she learned a language.

It's lovely that you’ve come away with a film and a marriage. It’s clear people in the village were welcoming to you but I see from the press notes that you also did have problems with the Iranian authorities at some point. Tell me about that because it must have been quite worrying for you to have that happen.

SK: While the production was taking place we had a home office in Tehran, which is about five-and-a-half hours away from this village. One time when we were in, in our home office, our apartment was searched by several people and our drives were confiscated. It was just a series of interrogations and we were banned from leaving Iran. It was all because we are independent filmmakers and we were questioned about what we were doing exactly, they searched through past projects. That was a form of basically creating fear and also stopping us from doing. We received the hard drives back after a month or so. So it was a terrifying experience and, I think in retrospect, even then we were just trying to figure out what we can do with the limitations we had.

|

| Sara Shahverdi. Mohammadreza Eyni: 'It’s not about a film coming from the northwest of Iran, it’s about a strong woman who's fighting against patriarchy and this is a global and universal theme' |

Knowing when to start a documentary is important but knowing when to stop one can be especially tricky, especially with a film like this, so how did you go about deciding when to switch the cameras off?

ME:Thank you for your understanding because making independent films is so hard as you can imagine everywhere in the world with a lot of uncertainties. Even now that the film is finished we, as filmmakers, need to think about self-distributing the film, because we didn't find a distributor.

So in each step we are facing uncertainties regarding the making of our films, finding funds to support our films and stories like Cutting Through Rocks, we needed to spend a lot of time to navigate what the story is about? What is the production regarding access and thinking about Cinema and making a film for a big screen. So all of these challenges. And imagine in the middle of this chaos, some people enter your house and say that you can’t do it any more – making a dilemma for you.

It was very frustrating. The most stressful time in our life, we were banned from leaving the country for one year, not being able to film in the village and we were not sure that we were going to finish the film. These were our emotions and I really don’t want any filmmaker to experience this in their lives. Nobody, actually. We finished the film and what you saw is the result of many risks and stressful days. I remember the Sundance screening at the Egyptian Theatre seeing it on the big screen for the first time. Sara and I just held each other’s hands and looked at each other. It was very emotional because we didn’t believe that we were there. The film was finished and there on the screen – unbelievable.So, this is the story of making Cutting Through Rocks. A lot of uncertainties involved, a lot of risks.

SK: When the case was closed for us and we were able to shoot. Three or four days afterwards we went back to production. We wanted to continue shooting.

I assume Sara has seen the film, what does she think of it?

|

| Mohammadreza Eyni: 'I was so happy when she called me because I'm from the region.. So, for me, it was an opportunity to make a film about the community that I'm coming from.' |

ME: In South Korea, many audiences, especially teenage girls, came to Sara after watching the film and they asked for autographs. They were taking pictures and sharing their own similar stories of inequality and suppression. And, for Sara, that was surprising, she said: “Guys, I didn't know that my story was going to connect to people on this level.” It’s not about a film coming from the northwest of Iran, it’s about a strong woman who's fighting against patriarchy and this is a global and universal theme. Seeing people reflecting on the story is so rewarding. It really is a gift.

How is Sara doing now, I read a school was being built in the village?

SK: So Sara’s four-year term in office came to an end and thanks to her efforts, they're building the building school. She continues to welcome women and girls into her house. She’s kind of like a self-taught lawyer and she continues to advocate for the rights of women and girls and she’s doing well. As I mentioned before, she’s gaining a lot of respect, even from her opponents.

So is your focus just now getting it distributed or are you thinking about other projects?

SK: We are in the process of developing different projects but right now, because this is a self-distribution effort, we are pouring our energy to continue to do that. But hopefully starting early next year we will be very happy to get back to production.

Cutting Through Rocks is currently screening at Film Forum in New York