Gastón Solnicki began his career in documentary with the likes of Papirosen before moving into fiction features, with his latest, The Souffleur, marking the end of a loose Viennese trilogy. It began with Introduzione all’Oscuro, a free-form tribute to Hans Hurch, the long-time director of Vienna Film Festival and continued with A Little Love Package, set against the ban of smoking in Viennese coffee houses and blending professional actors with non-professionals.

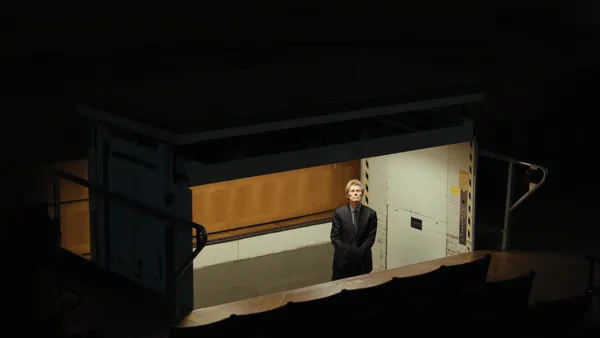

Stars don’t come much more professional than Willem Dafoe, who if you count shorts, has by IMDB’s reckoning notched up seven films this year, ranging from The Phoenician Scheme and The Man In My Basement to The Birthday Party and Late Fame. In The Souffleur he plays a hotelier who is facing – and fighting against – the closing of his establishment, The Intercontinental Hotel in Vienna. Solnicki again takes a loose approach to the material, with much of it improvised and pairs Dafoe with nonprofessionals, with Solnicki himself taking on the role of the developer looking to raze the hotel. The film played at Thessaloniki Film Festival this week, after its premiere in Venice. It will also play at Tallinn Black Nights We caught up with the filmmaker in Greece to talk about his unusual method and the challenges and opportunities it represents.

Your process is quite unusual, so could you tell us a little bit about your approach to filmmaking and this film in particular?

Gastón Solnicki: Being in Greece is actually a nice place on which to reflect on this because certain thoughts come in a very philosophical and natural way. This morning I woke up thinking about this beautiful idea, a quote by Walter Benjamin that half the art of narration is achieved when you don't explain anything. It's a good start. It's not everything. But there's something very mysterious about the film as a function of its process. I truly believe that films represent the emotions from which they're made. Are they generous? Are they courageous? Are they overorganised, pre-structured?

|

| Gastón Solnicki in Thessaloniki. 'I think paradoxes and oxymorons are the name of the game' Photo: Thessaloniki Film Festival/Studio Aris Rammos |

Then bringing William to a project like this was not just unusual, but I would say, even sort of suicidal.

For you or him?

GS: For both, double suicidal. But you know it ended up being quite a challenge. William is very generous, very courageous.I was so overwhelmed. In the editing where my films are really put together and written so to speak, then I don't understand how much he himself was exposed as an actor. We are very good friends now and we’re both somehow happy about the film even though it has been quite a challenge for both of us.

So when you arrive at the set, do you have a structure in mind within which you’re going to improvise, or how does it work?

GS: No, not really. I mean there is a vague idea of the space, of the possibilities. In fact, it is my most linear narrative, in a way, even though it's still fragmented and mysterious. I am very interested of course in this kind of tissue of digression and certain tensions. I understand this can be frustrating or challenging often for audiences, but I also believe there is something even not just within the avant-garde or the experimental but also within the form that I understood by showing these films. Like last night, for instance, a mother and a daughter, both doctors, came very moved, with tears in their eyes after the screening to hug me and thank me for the film. So what can I say? It’s easy to stereotype what people are expecting or how we're getting used to being exposed more and more to what we're supposed to like? But I also think there is a certain universal reward and pleasure also within this. Oral tradition, folk songs are also full of tension, digression… just like the music I love.

Yes, as you watch there's an element of almost free Jazz about it in a sense. Unexpected notes coming or a discordance coming in. So you do think about it in musical terms?

GS: Yes, I do think the way the films are put together has more to do with the way a composer works and the way film is usually broken down or structured.

So how did you meet Willem Dafoe? I think you said at the screening last night you met him at a festival.

GS: We met here in Greece but it was more like a screenwriting lab. William had a very clear notion that the films I make are not about this ABCD structure and he really encouraged me to keep it that way. But then, of course, when we started shooting things got a little complicated with the logistics. But somehow we made it work. He was very open and he really liked the people around and the non-actors were important for him. We wanted to work together and I proposed this project and part of the complexity is always the logistics, especially in a functioning hotel. But we made it work somehow. It’s the kind of film that the souffle metaphor stands for, in a way, the fragility and mystery of whether such an ethereal structure will rise.

Yes, the souffle rising as the building is falling, in a way. Did they take some convincing to let you shoot in the hotel?

GS: Looking backwards, I don't understand how they were not themselves paying us to do it because to bring Willem into the brand like this. So in a way it’s a bit silly that we had to fight for that so much but at the same time I could not have made the film in another hotel because it was so much about the building and the archives.

It’s certainly got a strong presence in the film, and so have you.

GS: Willem was like, “Baby, you’re going to do this. You come over here.” For me that's also my role as a director, I do believe it's a very physical and very personal approach. That you are there with the people. I’m also used to working on a smaller scale, more like friends, so, this was also one of the challenges in the film. It had to be made in a more professional way, which was difficult for the things that I care about, because often there's tendernesses, and these delicacies of character, of locations that are hard to access with the very noise of cinema. I’m very into direct sound – it’s not just a metaphor. Then the non-actors. One thing is to film them and another thing is to have Willem interacting with them or asking them to say lines. It can get very tricky.

Yes, it’s a real mix, especially because Willem has quite a specific style. He also brings a physical presence to this role, conveying character with a twitch of the shoulder as he puts on his jacket for example.

GS: That's the most difficult thing to do for an actor, as John Ford said, to open the door. That's why non-actors are so good also because they do it in a natural way. But Willem has also a very personal way of being and I think in a way it’s also an homage to him as a theatre animal. The souffleur has the idea of a theatre prompter and the idea of manipulation that we share in our crafts.

|

| Gastón Solnicki: 'I truly believe that films represent the emotions from which they're made' Photo: Courtesy of POFF |

The tension between being drawn to the documentary element and the theatrical is interesting.

GS: Sounds paradoxical, doesn’t it? I think paradoxes and oxymorons are the name of the game. I don't get discouraged by this, I embrace it. People often ask me how I draw the lines between genres but it’s the opposite. I want to get rid of them.

Were there challenges to shooting in the hotel?

Oh, yes, it was crazy! There were so many restrictions and the Austrians are so uptight. They were strangely worried about the guests. It’s funny because now they’ve changed the general manager and they’re very open and friendly, it would have been a very different experience. There were times when we set up a shot and they said, “No, you can’t shoot this.” The roof was also very difficult for insurance. I asked a friend to give us some hints about how to make a nice souffle and I sent this to the cook who was working there. They said: “You will not tell us how to do a souffle in our hotel.” I told them: “And you will not tell me how to do a souffle in my movie.”

Is that why you make the souffle taste bad in the film? Revenge in movie form?

GS: The cheese revenge.

So what’s next for you because this film is quite different from things you’ve done before. Do you think you’re going to continue with this evolution?

GS: I think this film sort of landed in the middle, the most indefinite zone, which is also very fertile between his world and my world, which was really difficult because there are all the challenges for small film and a big film and it's both at the same time. It was physically, emotionally, too much.. In the end it created its own very strange creature. But, for sure, I would like to work on both a smaller scale and a larger scale. I do have a project about my grandfather, who was a great chess player, that I would like Willem to play. He was a very famous player, not only a grand master but he invented some quite famous openings.