|

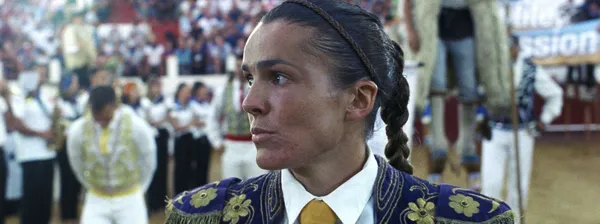

| Caroline Noguès-Larbère in Marion |

One of five works in the running for the title of Best British Short Film at the 2025 BAFTAs, Finn Constantine and Joe Weiland’s Marion is a character study with thriller elements set in the world of bull jumping. This traditional sport, which remains popular in the south of France, incorporates the risks and excitement of bullfighting without harm coming to the animals, as its human stars endeavour to dodge them, leaping and somersaulting around them. But there is far more to the film’s story than that, as the two explained when I met them to discuss it.

“It's an honour and a privilege, and amazing to find ourselves in this situation. I feel very proud,” says Finn of the award nomination, still glowing after several days. Joe, meanwhile, retains something of his initial excitement about the idea which led to the film.

“There was this amazing article that we read about Caroline [Noguès-Larbère],” he explains, referring to the film’s inspiration and star. “The quote was ‘I don't face the bulls. I face the men.’ That sparked this whole journey, taking this idea and framing it within this world.”

Caroline is the first woman ever to have taken an active role in the sport.

“Once we discovered the sport and came across Caroline and her story, we wrote a script and we moved to Paris to try and find a French production company,” says Finn. “We also spent a lot of time going down to the southwest of France where Caroline lives and watching these performances and observing and trying to integrate ourselves as much as we could within the culture. Obviously, myself and Joe, we're English and we had never seen this sport before. So before we thought about making a film, we had to understand the context in which that film lived. We had to become experts in this sport that we'd never seen before.

“We spent a lot of time researching, watching little films about the sport, trying to figure out which team members did what, how it operated, the internal process of it all. It was a really eye-opening experience and an opportunity to learn about something very culturally important in France and something that's been running since 1823. It was a fascinating process.”

Did coming to the subject as outsiders make it easier to translate it into the film in a way that would help anybody from anywhere in the world to understand?

“Yeah,” he says. “I think because we didn't have preconceptions of it, we really had to figure out what was going on. That allowed us to have a blank slate, and to make it about her and her journey rather than about the sport. And that was the main thing for us, is that we wanted it to be about Caroline – Marion – and her lived experience and her story, rather than about bull jumping. It's a very culturally specific setting, but the story is universal.”

There's a scene in the film where Marion is standing behind the barrier at the outside of the arena, and one of her colleagues comes over and slips his arm around her shoulders. i tell him that it made me think of the recent discourse about how many women would prefer to take their chances with a bear rather than with a man.

“ Yeah, exactly,” he says. “I'm happy that you picked up on that, because that's a small little nuanced moment that I think is actually really important. When you see it, it says exactly that. She would rather be facing the bulls than standing with these men that she's had to deal with backstage.”

Nevertheless, some of the male characters seem quite complicated. There's one who seems to be jealous that Marion has taken his place on the team. We see him bitching about her, but then he helps her when she's getting ready, and there's a bit of ambiguity there.

“That character was really interesting,” he agrees. “We wanted for him not to play both sides, but almost that. He's not allowed to accept her in front of his peers, but then actually behind closed doors or when he's just with her, there's this sort of...” He hesitates. “You don't quite understand what he's striving for. You don't understand what his intentions are, if he is against her or if he's is trying to help her. And the way that that scene plays out, where he's helping her get wrapped with the belt, we wanted it to be ambiguous, so that you can’t really put your finger on if he's a good guy or a bad guy. That adds to the tension. Leaving his motive and his intentions unclear was important.”

We also see Marion with her daughter, who is brought to the stadium and left for her to look after at an impossible time. There’s some ambiguity around that, too.

Finn nods. “The child character was super interesting because, you know, it does speak to a lot of different things. For me, ultimately, what I wanted it to do was show that Marion is first and foremost a mother. That's why when she picks up the daughter and she's running out of time, she still takes the time to have a quiet moment with the child and speak to the child and make her understand a little bit of what's going on, and keep her safe. But the fact that the kid walks up the stairs without Marion knowing, it speaks to the fact that Marion’s actions are going to inspire another generation, whether she knows it or not.”

Did they cast aroline as Marion purely for practical reasons, because of the physical challenges involved in the role, or did they always see something in her which suggested that, despite having no acting experience, she could bring somnething special to the film?

“There was nobody else,” says Joe. “We loved that she was such a strong performer and that was our thing. We were like, ‘It's Caroline or no-one.’”

“We wanted the story to be her story,” says Finn. “So putting an actor in the middle of the film, it just wouldn't have worked. It wouldn't have spoken to what we wanted to make. And the fact that she's a performer and, she does this every weekend in the summer, we knew that she had it in her to act and she could give a performance that would be inspiring and nuanced and sensitive, and she did all of those things. It was her or no one.”

Was she confident about that from the start?

“I wouldn't say she wasn't confident,” he says. “She'd never been on a film set before, so of course there was a level of nerves and a level of the unknown to that for her. But we really worked with her on the script and we spent a lot of time with her. We wanted her to be as comfortable as possible, even with the way that we ran the set. It was a very small set. We shot on film. There weren't big HD monitors everywhere. It was very – relaxed isn't the right word, because obviously it's always a little bit stressful in many ways. But, you know, it wasn't a dissection of her performance there and then. It was a very human experience. And we allowed her to be herself, which is very difficult to do. We allowed her to be herself in the right setting and in the right environment and pushed in the right directions to give the right performance.”

I ask if there wre other reasons for choosing to shoot on film. “There were a whole host of reasons. I mean, statistically, of course, we wanted this film to feel tangible and feel real, like you could feel the texture of the environment and the clothing and the arena, and film just lends itself to that type of feeling. And then, you know, it's an emotional thing. You know, you shoot on film compared to digital, it's instinctual. It's an atmosphere. It's emotion, and it hits you as soon as you see it. The story that we wanted to tell, there wasn't another option. It had to be shot on film.”

“It's a tradition,” Joe points out. “This sport is hundreds of years old, and we felt celluloid would really reflect that in the image. So that was another reason.”

One of the reasons why I wondered about that, I explain, is the nature of the stunt work in the film. One might script a thing like that, but it’s impossible to get the bulls to behave according to the script – how many takes did they need and how many times did they have to restructure the film to fit around what the bulls did?

“We shot that whole second half of the film, the bull performance, live over 30 minutes, in one go,” says Finn. “We had six cameras. They were digital cameras, and we shot it in a very documentary style. As you just said, you can't direct a bull. You can't ask a bull to do something again. It's just not feasible. So what we did is, we said ‘Look, we're going to set up this shoot. We're going to observe, we're going to document. We're going to do it in a cinematic way, in a way that allows us to find edit points in all of this. And then once we have our edit, we have our narrative, we'll bring that back to film so that it matches the first half.’

“It was a lot of time and effort and challenges to match the first half of the film to the second half of the film, because there were certain elements that weren't in our control that we had to sort of claw back. Of course, you're writing a hypothetical script, but the script that we had written, it wasn't too far off what happened. The ending wrote itself. How that performance went was how the film was going to end. So that was. We handed that over to the gods, essentially.”

Talking about the edit, there are quite a number of moments where everything goes very still and quiet. There is very careful use of sound and of pauses within the film.

“Obviously we wanted to create the loud atmosphere and energy in the arena, but I think contrasting that with the more quiet moments in the changing room with the little girl was really important,” says Joe. “We also wanted the sounds to sort of crescendo as she was getting closer to walking out. If you watch it through, you can really hear the drums getting louder and the atmosphere building. We worked really hard with our sound designer to build that soundscape of the world.”

Despite the pressures that marion feels around her colleagues because of their attitude to her sex, the audience in the stadium seems to accept her completely.

“That was natural,” Finn says. “I don't know, if we had gone to one of these performances X amount of years ago when Caroline was just starting, maybe the reaction from the crowd would have been different, but now...” He shrugs. “It was even more amazing, to be honest with you. Once we had finished shooting and Caroline came to sort of see us when we were sat in the stadium, it was incredible. These young girls coming up to her, asking to have their photos taken with her and wanting to shake her hand. To see that and to see that she really is an inspiration and someone that these young girls do look up to was pretty amazing.”

He tells me that based on what he saw, he thinks the sport will have a lot more female participants in future. As for the film...

“We want to see where it goes and develop it out,” says Joe. “We've had lovely response to the story. That's all you can really look for, and we're going to expand it, hopefully, and see where it takes us.”

“Saying that,” adds Finn, “It's very important to us that the short film is viewed as a short film. We set out to make a short film, and that was the structure and the confines that we wanted to work within. It’s important to me that people do view it that way, rather than as a trailer for a feature film or something bigger.”

If it wins a BAFTA on 18 February, it may become one of the most famous short films in the world.