|

| Ronald Zehrfeld and Nina Hoss in Barbara |

On a summery October afternoon, I spoke with Christian Petzold about his latest film Barbara, playing at the 50th New York Film Festival. We chatted on a rooftop overlooking Manhattan's FDR drive and the East River, near the United Nations, with helicopters circling above us, and the top of the Empire State Building peeking through the skyscrapers to our west. In other words, North by Northwest, meets Metropolis, meets King Kong, into a Rear Window.

Barbara had its world premiere at this year's Berlin Film Festival where it won the best director Silver Bear for Petzold and is Germany's entry for next year's Academy Awards for best foreign language film.

|

| Anne-Katrin Titze's rooftop interview with Christian Petzold, with the UN in the background, overlooking the East River |

The film tells the story of a young doctor, Barbara, who is sent to a small town near the Baltic Sea in 1980, as punishment for wanting to leave East Germany. Her interactions with the head physician of the hospital and the young patients make you question what freedom really means and how seduction can be a political act.

Anne-Katrin Titze: I was asking you about the Jugendwerkhof at your Skype Q&A press conference a few weeks ago.

Petzold: Yes, I remember the question.

AKT: You brought up Helmut Käutner's film Unter den Brücken (Under The Bridges, shot in and around Berlin on a barge during the final months of the Second World War).

CP: Yes, that's one of my favorite movies.

AKT: I taught an intensive course focusing on Käutner a few years ago here in New York. It is a great film. He is not really known outside Germany.

CP: Actually, I have to go to Paris in three weeks. They are doing a retrospective of my movies and I had to decide on two movies which are very important for me. And one of them will be Unter den Brücken by Helmut Käutner.

AKT: And the other one? Is this at the Cinémathèque?

CP: Goethe Institute and Cinémathèque, both. The other is from 1970, from Munich, by Klaus Lemke. The name of the movie is Brandstifter.

(At this moment, fittingly, Petzold excuses himself to toss his cigarette butt - Brandstifter is German for arsonist)

AKT: How did you come to cast Ronald Zehrfeld as the young doctor?

CP: He is always a policeman. Very hard, very brutal. I like his sad eyes. I like men with sad eyes. I think every hero who is important in the history of the movies is a sad man.

AKT: Like the heros in Käutner.

CP: Yes, as if they know each kiss could be the last. When you start a love affair you feel the end of the affair at the same moment. In Germany, when you play a policeman, you always play the policeman for your whole life. You have to wear a uniform your whole life, or you are the sadistic killer your whole life. So I said to him (Zehrfeld), in my movie you are a doctor, an intellectual doctor, who is reading and makes interpretations of Rembrandt paintings. And he said, 'Oh, I never played that.' But he is intellectual in real life. I like it when someone receives a new character, so he is working in a fresh and new way.

AKT: You like doing that anyway, don't you? Your casting is never what one would expect. Which makes the characters so real.

CP: Yes, I'm always thinking about that. Cinema has something to do with dreaming. You are in the audience, you are sitting there, you are not at home, you are awake, and you are sleeping in the same moment. When you play a character you haven't played before, it's also like a dream. This imagination to be someone else, this desire, has something to do with cinema.

AKT: Your film in the Dreileben trilogy (Beats Being Dead, 2011) is more about escape than Barbara is.

CP: Yes, I agree.

AKT: You'd rather want to escape from there, the stagnant modern small-town world of today, than the GDR in 1980 at the Baltic Sea you are showing in Barbara. She does not necessarily have to get out, you show that through the little utopian niche, a bubble of caring.

CP: Yes, exactly.

AKT: I also want to ask you about the very specific objects. The sofa cushions, the texture of the materials, the bike repair, the burnt out socket, the filthy bus schedule, all these things make you feel as if you were able to touch the screen.

PETZOLD: I think there are two worlds of things. One, where people use and touch things, they have to be real. Sometimes in Germany, the actors, who always come from theatre - in Germany theatre is very important - when they open a window or drink a glass of water, they always make an expression out of it. That's why I need realistic things so the actor has to be realistic like the thing.

|

| Eggplants for three ratatouilles Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

And the other [world] has something to do with my admiration for Fritz Lang. You have a conventional story, for example, and then there is a shot from the world of things. The wheel from the bicycle Barbara puts under water, for me was a very important image. Another example is the plate with the vegetables. You have a hand and you have vegetables. It's very sensual. Because Barbara is a tank, she is leather skinned. At this moment her hand is also leather, sort of arrogant and hard, the hand of a doctor, who is not a woman any more. And this hand touches a tomato, an aubergine, and an onion and she says the words. It's like someone who comes out of prison or a hospital and sees the world with a new innocence. The sensual and sensitive world starts again for her at that moment.

AKT: Did you know that your film is the third movie in this year's New York Festival where someone prepares ratatouille?

CP: No!

AKT: Jean-Louis Trintignant serves it to Emmanuelle Riva in Haneke's Amour and in Camille Rewinds, the character cries because her father always made it. Interestingly, in all three films it is men cooking ratatouille.

CP: I've had so many problems with the audience in Germany because they said to me, there was no ratatouille in the German Democratic Republic. I was in the library and there was a cookbook from the GDR from 1974 and on page 312 there is ratatouille! And they don't believe it! They said, there were no eggplants. No, there were some farmers around Berlin where you could buy eggplants (aubergines). They don't believe me and I tell them, why are you a victim of the propaganda from the west, that you don't have anything? You have something. What you don't have is imagination.

AKT: Tell me about the man from the west, Gerhard, who is so slimy, and reminds me of certain business men, a masculinity I found very disturbing in my childhood.

CP: These men visiting East Germany from the west were all agents in their big cars with their tanned skin looking for girls. I don't like them. They are all agents of capitalism, the male subjectivity of the capitalistic world.

AKT: The scene in the forest is brilliant. I remember how I felt as a five-year-old, thinking, if this is what men are like, I don't like this. You captured all of that attitude beautifully.

CP: This guy, the actor, Peter Benedict, he is so fantastic, a really good guy. The costume designer Anette Guther found him a suit from 1979. And he said, I cannot wear that, that's the suit of my father. But it's great to have the suit of your father, I said. But I hate my father, he said. After half an hour, he took the suit and, I think, he is playing his father.

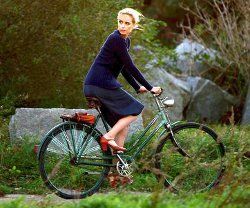

AKT: Let's talk about the costumes. I loved what you put Barbara in. The coloring of the jacket matching the brick wall.

CP: There are two things. One thing is that in the GDR, the material was very very bad. When you have bad material, you want to distract with colour. So the GDR was very colourful. And then, Romy Schneider in the Seventies was the heroine of the German Democratic Republic. Each day on TV you could see a Romy Schneider movie.

They did the dubbing in the East for her Claude Chabrol movies, for example, because she was so famous there. And every costume she wore in the movies, they copied. So we found some pictures, copies of Yves Saint Laurent suits, all based on Romy Schneider movies with Michel Piccoli, for example. And we researched all the costumes for Romy Schneider and also the mascara and the lipstick, the make-up and also the hair style and we copy it, like all the girls and younger women and older women of the GDR.

AKT: I thought it looked great on Nina Hoss (Barbara).

CP: But you can't use the cheap material, because it doesn't work when she's on the bicycle, so we had to use the originals. On the bike there is wind and I wanted the whirl grabbing her - the material must be light.

AKT: So you used vintage Yves Saint Laurent?

CP: Yes. So when people ask, I have to say it's from 1979 Yves Saint Laurent, you can't find it any more.

AKT: Which of the costumes?

CP: For example the brown jacket, you were talking about, it cost us 2500 euros for rent.

AKT: There is a beautiful scene with the waitresses having their legs up, to prevent varicose veins, we are told.

CP: My grandma had a little restaurant in the GDR and, I was maybe nine or ten years old, when she had two girls working there for her, with her. Once I came into the room and they lay on the floor in this position (legs up against the wall). I was astonished and it had a little bit of a sexual atmosphere for me because I saw naked legs. I was totally confused about this picture, I was ten, and I asked my mother and she told me it was because of the varicose veins.

AKT: It's perfectly placed in the film. Suddenly we are in an Esther Williams movie.

CP: We gave the scene the name, the Can-Can of the German Democratic Republic.