|

| Ashley Thorpe's animation illuminates Woodlands Dark And Days Bewitched: A History Of Folk Horror Photo: Fantasia International Film Festival |

It’s not often that a three hour documentary emerges as one of the most popular choices at a film festival, but at this year’s Fantasia it’s widely agreed that Kier-La Janisse’s Woodlands Dark And Days Bewitched: A History Of Folk Horror is a standout. It’s not only a film of major importance in recording the history of cinema, it’s also tremendously enjoyable from start to finish, densely packed with information and utterly beguiling. The secret to that seems in part to be Kier-La’s infectious passion for her subject, so when we met up during the festival to discuss the film, I asked her where that passion began.

“I was a really big Wicker Man fan as a teenager, and everything kind of grew from there,” she says. “But when I first started making [the documentary], originally, it was just going to be a short thing for Severin Films, a DVD extra on The Blood On Satan's Claw. And so I wanted to have maybe a 30 minute little rundown on what folk horror was, and the impact of it.

|

| Blood On Satan's Claw Photo: Fantasia International Film Festival |

“Around 2012 or something, I started really diving into a lot of the old British TV stuff. A friend played The Stone Tape for me. And around that time there was a new Ghost Story For Christmas that I was able to see while I was in the UK, like, in real time, like on Christmas Eve. And, you know, when I started thinking...it's these films’ relationship to a lot of bands, and the music and stuff that was coming out around that time, like on the Ghost Box label. There just seemed to be this really interesting subculture brewing around these films.

“So originally, it started with an interest in that. I wasn't even thinking of something that was remotely in the grand scale that the film ended up being, it was really just kind of like, ‘Oh, this is interesting that there's this subculture that's kind of grown up around these films where people are expressing a fascination with older beliefs,’ you know? And there's a lot of ambiguity depending on the film and how they feel about those beliefs. I think in terms of me being driven to actually do something with the material, it would have been around the time of like, A Field In England. Me just being like, ‘Oh, there's all these really interesting connections happening here.’ And that was the thing that made me propose the idea of doing a feature for Blood On Satan’s Claw, which ended up turning into this.”

She enjoys visiting film locations and tells me about a trip to Plockton to see the harbour where scenes for The Wicker Man were shot.

“The harbour master’s boat is still there, in an old shed in the woods, and, you know, it's such an iconic little boat, it's like a red and blue boat with the eyeball painted on the front of it. And so I went there and I found it. That was actually, I think, where my interest in trying to find and go to film locations began. Right around the same time, I made a trip to Providence to see a bunch of HP Lovecraft related locations.

|

| The Wicker Man boat |

“It's such an interesting feeling, such a weird feeling to go to these places that have this magical quality to you, that are just everyday places to the people who live there. They walk by that place all the time and it means nothing to them. And so to be in the middle of that and be like I'm having this like mystical experience with this building or whatever, that nobody can see. Like even that separation between yourself and everybody else at that moment is pretty much, you know, it's like you're in this little bubble where only you can see the ghost of this thing that used to be there.”

I mention that I once spoke to Robin Hardy about The Wicker Man and his fascination with folk horror, and for him the really magical place was Iceland. We talked about the way that stories spread around the world. Woodlands Dark And Days Bewitched has a great international section looking at stories in different places, and I particularly liked the part about the US, because obviously it has its own older stories, but when European settlers arrived there, did they need folk stories to start building a nation and a sense of community?

“Oh, definitely,” she says. “Each section of the movie kind of had a different approach and I feel like the American section definitely had more of a geographical approach in terms of like, it kind of moved out across the states, the way that America was colonised. It moves to the different areas and follows the different threads of people and the kind of ideas that become prevalent in those regions. We did that with the ‘States much more than we did with Britain or with the other countries, just because it's such a huge country, it actually does have all these distinctions regionally.

|

| Reflecting on folk beliefs in the Americas Photo: Fantasia International Film Festival |

“But I think that, yeah, folk stories and folk beliefs were extremely important to gluing people together in a precarious environment. Obviously, some groups of people had religion, and their religion would tie them together, but then there would be splits and people would go off and form other smaller colonies. But there were also still lots of people who were not especially religious, who moved there for other reasons, you know, like they were trying to get away from from debt, or coming from the Scottish Borders and dealing with constant skirmishes and things like that. Or they're dealing with starvation, or they're dealing with feudal landlords or, you know, just all kinds of things that people were trying to get away from.

“People move, they're thinking it's going to have all this opportunity for them. And the folk songs and the folk stories and things like that would be things that tie people together, and they would get mutated as they moved and as they interacted with indigenous cultures. The Appalachian region is kind of amazing for the confluence of cultures that they have there because you've had, like, all these people from the Scottish Borders who moved into that region, but then they had contact with indigenous cultures fairly early on, but then you had a lot of freed slaves that moved into that region and brought beliefs like Hoodoo and things like that. Even now, in that region, the spiritual beliefs of the people who live there are so mixed from these different cultures that settled there.”

The film is dealing with a huge subject, and it's easy to ramble in any one area, so something I was really impressed by was the structure of the film and how tight it is and how naturally it flows. How did Kier-La and her team achieve that?

“Well, I mean, I would have to give the editors credit,” she says. “When I scripted it, it was not something I'd ever thought of. Before I made this film. I would always see writers’ credits on documentaries and I was like, ‘How is there a writer? It's real.’ And it wasn't until I made this movie, I was like, ‘No, it really is scripted.’ Because there's so much information. You basically are taking a sentence here and a sentence there, you're basically writing a script.

|

| Il Demonio Photo: Fantasia International Film Festival |

“I started off making a rough cut of the big sections, About halfway through, I realised it was just easier to look at the script on paper and see if it worked, before you start moving everything around, and then realise it doesn't work. You have to hear the story in your head without the pictures and has to make sense, you know, just hearing the words. And so, I had a script. And then the editors were the ones who really made it all beautiful and amazing. There was a rough edit that I did, where I would drop in clips from certain films that I thought were relevant to this or that, you know, but in some cases they would completely throw out clips that I chose and pick different clips.

“In some cases, more elaboration would be needed, or better transitions would be needed for this idea to actually sink in for people. And so then sometimes I would just go off and do more interviews to try to fill in those blanks. It was really important that it not feel jarring and choppy, you know, because there's so much information. I really wanted everything to kind of organically flow into the next thing.”

Was it difficult to get hold of some of the clips?

“Oh, well. Everything is fair use,” she says. “Very few of the clips we actually had to get licenced. The fair use lawyer had to go through everything and approve it. There would be cases where he would be like, ‘This needs to be cut and that needs to be cut.’ And so we would then have to make a choice of whether we were willing to cut that thing, or if we then had to go to the company and actually try to licence it. But I would say for the most part, the stuff that we did have to licence, everybody was really reasonable, because honestly, sometimes the clip is only 10 seconds. And then finding the actual films and stuff like that is just having a network of movie nerds around the world.” She laughs.

There’s so much information in the film that it really feels as if each section could be a film in itself. At one point, she says, she considered making it into a television series, but she was daunted by the amount of bureaucracy involved.

|

| A Field In England Photo: Fantasia International Film Festival |

“I just felt like it wouldn't get made, you know? To do that would be like two more years of trying to pitch it to somebody and trying to get money from them, or whatever. And I was just like, ‘Well, we're just going to make the movie. And then if it turns out that anyone is interested enough in the movie that they liked the series idea, we do have a lot of footage that we didn't use.’ Especially for the International section, I feel as though like all those countries that we touched upon, and even countries we didn't – like, we didn't really go into Spain or France, there's tons of countries that we didn't really address.

“I think it would be easy to have a series that was like a spin off of the film, where you went into all those cultures a bit more, like the American section does, where it goes across changes in the culture over time and gets more into the history of things. And shows more films, because obviously at a certain point, for certain countries, I knew it was going to be like, five minutes, you know? I was like, we're going to be talking about Mexico for five minutes, you don't want to put in hours of interviews. I've got all these movies. And then sometimes things wouldn't be included just because we couldn't find good enough copies of the film. But I do think that there's a lot more to explore there, if anybody’s interested in that series.”

With this kind of thing, no matter how well one knows the subject to begin with, it's always a learning process because there just is so much volume of material involved. So in relation to that initial question, ‘What counts as folk horror?’, does she think that her answer changed over the course of making the film?

|

| Dark Waters Photo: Fantasia International Film Festival |

“I don't know that my answer changed,” she says thoughtfully, “because often my answer would be vague. It would be kind of like, you know, ‘Something that's set in a rural environment that has some level of engagement with folk customs, practices or beliefs,’ and I still think that that, you know, whether you're looking at Anglocentric folklore or European or Asian folklore, I think that definition still works. But what I would say is that I learned how British my perspective was going in. For so many people really, that is the viewpoint. It’s like British folklore and then how does everything else relate to Britain? I was trying to open that up, so that the perspective of the film was not British. So that it was giving proper veneration to all of the films and books and texts and everything that came out of that culture, while not making it the prism that everything else was seen through.”

I suggest that part of the reason why it’s seen that way is the impact of folklore on children’s television in the UK in the Seventies and early Eighties, a subject which is discussed in the film.

“Yeah, well, I'm interested in old weird kids’ film and television and I've written a fair bit about it. And so yeah, things like The Owl Service and Escape Into Night. It's interesting because so much of what people go for, especially when you ask people how they define folk horror or what films they consider folk horror, so much of it is associated with that.

“We had a section on music in the film that wasn't really working. So it's going to be in the extras. But, you know, somebody – I think it was Darren from Folklore Revival – was saying that when you're talking about folklore music and songs, it's not even a sound that they have in common. You know, because you'll have, like, experimental electronic music and then, like, traditional folk, and industrial music and whatever, and they'll all be considered connected. And he's like, they have nothing sonically in common with each other but there's some sort of mood, or there's some sort of associations they share that makes people put them into the same category.

|

| Witchhammer Photo: Fantasia International Film Festival |

“I think for both for films and television, it's similar in a way. If you really break down the film, or whatever, it doesn't have all the key notes of folk horror, or all the trappings that we would expect in a folk horror film all the time, but there is some real quality that they share.”

I tell her that I've had a longstanding interest in the subject but I still went away from the film with a list of things that I'm going to have to track down and watch. Did she discover new things herself whilst making it?

“Absolutely,” she says. “There was tons of stuff people would mention that I'd never heard of. Jonathan Rigby brought up Lake Of The Dead, the Norwegian film. I had never heard of that movie. There was a bunch of the Mexican films that I hadn't heard of like that. Abraham Castillo Flores introduced me to a bunch of films through the process of this, but at the same time, he was preparing a Miskatonic class on his dislike or school that I started. And so he was doing a class there and Mexican horror kind of around the same time we were filming him for this. And so through his class and through my interviews with him, I learned about a ton of movies I've never heard of.”

We talk about Brazilian horror cinema and the recent tragedy at the Brazilian Cinematheque in Vila Leopoldina.

“It was shut down during Covid by the government, all the people were fired,” she explains. “And so everything's been completely abandoned. And it's like the entire country's film history is in that single place. And there was a massive fire. They lost like 2,000 films, all the negatives and everything. The only place any decent copies of these films existed was in that cinema. We couldn't access them for the documentary because the place was closed and nobody had access to it, and now they may actually be lost forever.”

|

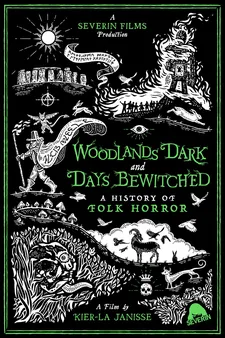

| Woodlands Dark And Days Bewitched poster |

Woodlands Dark And Days Bewitched will screen at Fantasia shortly and then go on to Frightfest, which isn’t something she ever expected.

“I thought maybe I could submit it to Brigadoon. The Sitges Film Festival in Spain has a section called Brigadoon which is free, and so they will often programme DVD extras and things like that there, and people can kind of come and go. That was like the only thing that I thought maybe I had a chance of getting it into. The fact that we submitted it to SXSW was really just to create an internal deadline for ourselves. We didn't actually expect it to get in! And then when it got accepted there that I was, like, ‘What?’ So that was amazing.

“Every step of the way it's been amazing, because it keeps exceeding my expectations. I'm more worried about Frightfest because it’s a British audience and the first third of the film is so much British stuff that is so familiar to British audiences. You know, even when I was interviewing some of the British scholars, they were already so sick of talking about folklore. I'm wondering whether it will hold the same interest as it has for North American audience. The concept and folklore in films is much newer to them. So yeah, we'll see.”

Woodlands Dark And Days Bewitched: A History Of Folk Horror is screening at Fantasia on demand and at Frightfest on 29 August.