|

| Finsterworld's Christian Kracht and Frauke Finsterwalder with Anne-Katrin Titze in New York |

On a sunny morning on Broadway, high above Houston Street, I met with filmmaker Frauke Finsterwalder and her co-screenwriter, author Christian Kracht, to speak about their intricately constructed Finsterworld. We discussed why the film could only have been written from outside, childhood obsessions allowed to artists, fairy tale houses made of food and Wes Anderson's stylised truth.

|

| Sandra Hüller as Franziska: "Actually, she wants to scream at him 'Can't you say something? I'm wasting my time'." |

This is the Germany of the unconscious where Teutonic earth spirits coexist with pedicurist Claude (Michael Maertens), who, in a raspberry colored turtleneck, works foot-magic at a nursing home. Margit Carstensen, the star of Rainer Werner Fassbinder's films, plays Maria Sandberg, the object of his special affections. In loosely connected strands we meet the different generations of the Sandberg family. Georg (Bernhard Schütz) and his wife Inga (Corinna Harfouch) are living their passion and frustration in a rented Cadillac, cut off from the German ugliness outside on their way to Paris. Their son Maximilian (Jakub Gierszal) and his classmates Natalie, Dominik and Jonas (Carla Juri, Leonard Scheicher and Max Pellny) at the boarding school are going on a school trip to a concentration camp. Documentary filmmaker Franziska (Sandra Hüller) is confronted with the fact that her policeman husband Tom (Ronald Zehrfeld) is a furry.

Lovely to look at and scary as a lion's den, Finsterworld grabs us by the hand and abandons us in a forest glimmering in fairy dust where an injured raven is rescued by a hermit (Johannes Krisch).

I spoke to Frauke two days earlier and mentioned that the scariest thing about her film was the possible discovery that one could be any one of those characters. "That's probably why we wrote the screenplay. The reason I think why I made the film - to get over those kind of fears," she told me.

A protagonist of the film is the German language itself. Precise, dangerous, disturbing and spellbinding, Finsterworld celebrates words of lore as well as colloquial rhythms and structures of non-communication.

|

| Margit Carstensen as Maria Sandberg: "It also means he couldn't touch me." |

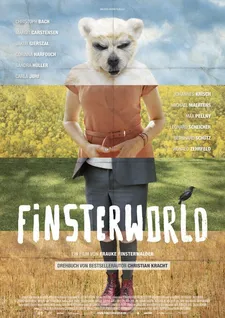

Anne-Katrin Titze: I'd like to start with the poster. The concept of the poster is that of the children's game. [You draw the head of a figure, fold it over and hand it to the next person who blindly continues the drawing of a body].

Frauke Finsterwalder: If we would have had a higher budget we would have made several [posters]. It also has something to do with the fact that we never really know who the characters are because they don't reveal their personality. It's a lot about costume. Like the furries trying to be someone else in order to get what you want.

AKT: The poster already introduces us to the childhood theme and the ideas about fairy tales. The tale that I was most reminded of was Allerleirauh [the Grimms' tale All Fur]. Did you think of that one?

FF: No, but I read it as a child. Which one is this?

AKT: It's the incest tale. The king wants to marry his daughter and to dissuade him she asks him to make three dresses for her - as bright as the sun, the moon and the stars and, eventually, a coat made from the skins of all the animals in the kingdom.

Christian Kracht: That's a cheery German tale!

FF: I remember that. I was obsessed with those dresses.

AKT: I thought about it because of the fur and that somebody would make a costume out of all the different furs of the kingdom. That's very much your film.

|

| A Finsterworld furry: "Like the furries trying to be someone else in order to get what you want." |

CK: It is true. All these archetypes they are always with us, especially if you are vaguely Teutonic in your "Geisteshorizont" [literally - the horizon of your spirit]. It's interesting that you mention that. I think it's just part of our culture.

AKT: Were there any specific tales you were referencing?

FF: Hansel and Gretel. The oven, the cookies, the concentration camp.

CK: Is it "Plätzchen" [cookies] on the witch's hut in Hansel and Gretel?

AKT: "Pfefferkuchen" [gingerbread].

CK: There you are - "Pfefferkuchenhäuschen" [little gingerbread house].

FF: Our daughter is totally obsessed with the song. The whole way we approached the film through obsessions. It's a very childish thing. Children are very much like that and it's something that adults lose. Not all of them. The good thing about artists is that they are allowed to continue being obsessed with things in a playful way.

AKT: Things, culture can sneak up on you, like these tales, in unexpected moments. Language does that.

FF: And that happens very much if you don't live in your own country. We wrote the screenplay in Korea, Fiji, Argentina - most of it in Argentina actually - where we had no connection to our culture or language. When you come back to your own country, suddenly you understand everything people are saying and all these words come along. I think in order to go back to this child version mode that was only possible because we were not where we come from.

AKT: I wrote down a few lines where the language amazed me. "Ich schenke Ihnen diese Fusscreme." [Claude the pedicurist says to the policeman who stopped his car "I gift you this foot lotion".] I found the verb such a strange beautiful choice. It's his attempt at bribery and very much in character.

|

| Finsterworld poster |

FF: It's very much Claude who wants to be overly polite throughout the whole film. Speaking of this - in the film some people apologise all the time. They say "I'm sorry" all the time.

CK: It's the last thing that Dominik says when he comes up with these ritualistic things to do to change his life. The last thing is "to apologise".

FF: When Maximilian and Jonas run out and Maximilian is so angry that Jonas has forgotten his scarf there, Jonas apologises. It's not about the scarf, it's a general failure to live up to the expectations of the idol.

AKT: I didn't pick up on the apologies, only on the general feeling of guilt of the characters. Another line I liked is " Also ich esse ja ungern alleine, und Sie?" [I don't like eating alone, how about you?"] The rhythm. It felt as though I were overhearing something at the next table.

CK: And then suddenly a whole culture would fall back into place. Through a linguistic turn.

AKT: Precisely.

FF: Also, we thought about the politeness they all had, even the young ones. Usually in German films they would have a totally different language. That's also the reason why they were not allowed to improvise at all. Especially the young ones.

AKT: So in a way it was good that two of the boarding school kids weren't German speakers?

FF: In a way. It was hard because they knew a little German. They had to learn their lines like you would learn Shakespeare.

AKT: I did not pick up on it that they weren't native speakers. It was a stylised fit. They have a Wes Anderson feel to them [in Moonrise Kingdom] that I also thought matched the language.

FF: You mentioned the line that Franziska [the documentarian] says to the guy [her subject]. Actually, she wants to scream at him "Can't you say something? I'm wasting my time." And she doesn't. She is overly polite and holding back her aggression. There's a moment too when he touches her, which I hadn't really thought about. In Germany, it would be overstepping a boundary. I noticed that when we were in Asia. In Japan it would be so horrible the way the man touches her, gently. What I'm saying is, that all these characters, they hold back a lot of aggression. They use the politeness so that they don't explode. The one character that does explode is Georg. Every time I see the film it's a relief for me when he does.

|

| Carla Juri as Natalie Jakub Gierszal as Maximilian: "They had to learn their lines like you would learn Shakespeare." |

CK: I have a lot of pent up aggression. I just wanted to say that, because you mentioned it, that some reviewer in Germany, which I thought was interesting, said that we had created a sort of very stylised dialogue which is at the same time hyper-realistic. That it was more truthful than usual cinematic dialogue writing in Germany because the pitch was somehow better. I was very happy with that. The tone, like "Ich hab so Lust auf Thai-Essen." [I am really craving Thai food].

AKT: "Ich lieb das ja wenn's gut gemacht ist." [I really love it when it's well done]. I liked your slight shifts about gender and cooking. Mrs. Sandberg comments that her first husband couldn't bake for her. It is treated as the most normal thing in the world that the men would be doing the cooking. Do you cook?

CK: No, I hate it.

FF: You are a good cook.

CK: No, I'm not.

FF: I have to say that there happened to be a huge cooking obsession over the last ten years in Germany. Men are doing it.

CK: Bakers are men.

FF: True. Traditionally the man bakes and the wife sells [in the bakery]. Sometimes it's really too much. With a lot of our German friends the men are into cooking. But they only cook when they invite people and then there are large conversations about the food and where they bought it. In England it's the same ever since Jamie Oliver came out with this whole thing that men can now cook.

AKT: It's interesting, though, that you have Margit Carstensen's character say that about her husband who came back from the war. It's as though it had always been the tradition that she should have been baked for.

FF: It's also important that the moment she says that, Claude is massaging her feet. The husband couldn't bake because his hands were shattered. It also means he couldn't touch me. They are talking about baking and actually talking about something else. That is actually the first hint.

CK: I'd like him to bake for me some more. Touch me more, she [Mrs. Sandberg] means.

This is a film about donning skins more than shedding them. Scraping, rather than unveiling. Ashes, foot dust and fur fluff invade body and mind. Truth comes with a price and the feeling of disgust is worth a second look. In that respect, Finsterworld is profoundly universal.

In part 2, Slavoj Žižek beyond The Pervert's Guide To Ideology, Klaus Theweleit's Male Fantasies, Berlin architecture, Kubrick's The Shining and the legacy of "Gesichtswurst".

Finsterworld will be screening at the Edinburgh International Film Festival on June 21 and June 27.