|

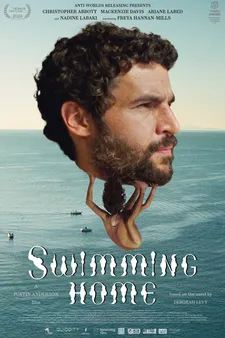

| Swimming Home |

Director Justin Anderson's feature directorial début, Swimming Home, is an adaptation of Deborah Levy's novel of the same name. It revolves around Joe (Christopher Abbott), a celebrated poet who is struggling to write, and his partner Isabel (Mackenzie Davis), a war correspondent, who tolerates Joe's frequent affairs.

When they arrive at their rented Aegean holiday villa with Isabel's friend Laura (Nadine Labaki), their daughter Nina (Freya Hannan-Mills) surprises them by announcing that there's a naked lady in their pool. Unexpectedly, Isabel invites the stranger, Kitti (Ariane Labed), to stay. In turn, she exposes the fractures in Joe and Isabel's relationship and forces Joe to reckon with his repressed memories.

|

| Justin Anderson |

The theme of encounters is a common thread in Anderson's films, beginning with his 2014 short film Jumper, about the disruptive effect of a stranger on the lives of a bourgeois family. In 2016, he directed an adaptation of Guy de Maupassant's short story The Idyll, about an unexpected encounter between two strangers travelling in the same train carriage.

In conversation with Eye For Film, Anderson discussed his interest in the peculiarity of truth, and his desire that the audience absorb and not overthink the film. He also spoke about his love of the Spanish surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel, the human need to understand and how it's all just a ride.

Paul Risker: How would you describe your relationship to cinema, and are there any filmmakers that have left an indelible mark?

Justin Anderson: I would describe myself as a voyeur and cinema is a view into another world. It's a way of being able to sit in a room with people and watch them.

The one film that I watched over and over again as a teenager was Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture Show. I'm not from Texas, but I loved it.

It's funny because it was shot in black and white in 1971, and so, it's already a nostalgic film or a film about nostalgia. And every time anyone turns on the radio, it's Hank Williams. So, it's very stylised, but I find even talking about it, I have a genuine love for it. So, there's also love there, like falling in love properly.

Also, when I was a teenager, I really loved [Luis] Buñuel. The craziness of Buñuel totally blew my mind. I had a schoolteacher who used to just show us Buñuel. We'd go into our 45-minute art lessons, and we'd watch half of a Buñuel film, and then we'd go to geography. I remember watching That Obscure Object of Desire, which has two actresses playing the same character. At the time, I was a teenage boy trying to wrestle with the idea of women and create relationships with the opposite sex. I was totally blown away by the truth of the idea that a woman would walk out of the room as one person and come back in as another.

|

| Swimming Home |

It is the peculiarity of truth that I really like, and that is perhaps a little bit voyeuristic. […] I'm not that interested in drama; the story doesn't interest me. The thing that interested me about Buñuel was that peculiar portrait of human nature, which was that people can walk out of the room as one person and come back as somebody completely different. That felt surprisingly real and that surreality is actually realism.

When I think about being a teenager, I didn't absorb the kitchen sink drama. I was much more on the Buñuel and Fellini side of things. That's where I found my truths. When I read the Deborah Levy book, one of the things that struck me was that I didn't really understand these people. I didn't think, 'Oh, that's why they're doing that.' And if I did, I was wrong.

The book presents itself as being about this stranger in the pool. So, okay, it's gonna be an erotic thriller, or it's about desire, or family relationships. But it just keeps veering off and there's something uneven about it, which is real because human relationships are uneven.

PR: Swimming Home is all about the question of truth. The characters themselves are trying to understand who they are, and what they know, they may have repressed. The truth is therefore lost in the shadows, and it doesn't appear that you're interested in pulling out of the story the answers to those questions. Instead, you're happy for you and your audience to be lost in the uncertainty.

JA: Yes, because that's where the truth actually lives, in the shadows.

|

| Swimming Home |

I've just come back from spending time with my family over Easter. I don't sit there and know everything, nor do I tell everyone everything. All of us are like icebergs — you only see the very top that people want to show. Most of it is full of uncertainties and projections of what you think. So, even when you meet somebody, you might think you know who they are, but then you realise you actually don't know them. That to me is truth — it's uncertainty.

[…] I've shown the film around the world at film festivals, which is an incredible part of the filmmaking experience. You talk to people from different backgrounds and cultures and talking to Polish 20-year-olds, they absorb things differently. I would love people just to absorb and not overthink the film.

One of my criticisms of criticism is that we all try and put things in the box too much. As human beings, that's how we negotiate the world, because it's so difficult to understand. You and I sit there in our comfortable, nicely heated houses, and we flip open a laptop and experience the most horrendous things going on in the world. Then we have to decide what we're going to make for our supper. There's an incredible amount of stuff that we have to carry around, and it's complicated. But it's okay. We can change our minds, make mistakes, fancy the wrong people and do all sorts of things that really make no sense.

One of the first things that happens in the book is that Isabel invites this stranger into her home. I just thought, 'What on earth are you doing, Isabel?' I had no idea why, and I really liked that. I guess that's what therapy is about — we try and figure out why we make the choices we make.

|

| Swimming Home |

PR: The film is also an exploration of power dynamics, and how characters have and lack power.

JA: Absolutely, it's who is zooming who, and you just don't know because they're all zooming themselves. And that's what I think is real. There's not this idea of the good guy and the bad guy, which I think is dangerous. As we well know, life is not that simple.

Most of the time, storytelling is an attempt to simplify things and give them meaning. To say, well, if you do this, then this will happen or if this person's bad, then either this will happen to them or there'll be some kind of retribution. In this story, Joe's this very irritating man who dies at the end [laughs]. So, what are you going to do with that? How is the daughter going to be when she grows up, and she looks back at those four days she spent with her dad and this stranger? It's not really a balance; it's just a big mix of humanity.

PR: There are moments where Kitti resembles a serpent-like creature, who leans into ideas and interpretations of the devil, leading one to perceive a biblical context to the film's metaphorical storytelling.

JA: The book was originally set in France, and we moved it to Greece for logistical reasons more than anything. But the Greeks have really figured out humankind. There's this very morose man with one eye in the middle of his head who goes around eating people and there are the Greek Sirens. They have these characters that are fundamental parts of humanity.

|

| Swimming Home |

There is actually one line in the film where Kitti says, "My mother was a river." That was her telling the truth, because if she came from the underworld, her mother would be a river nymph. So, I was playing with these ideas and definitely, through my conversations with Ariane, we wanted to explore the beast within the person, which was similar to her conversations with Candela [Capitan], the film's choreographer.

I don't know whether it's necessarily biblical, it's more that Ancient Greece filtered in, just because it does. When I went to the museum and I saw some of those big figures that stood straight, this gave me an idea for the boys on the rocks. You don't really need to scratch the surface much in Greece to find an awful lot of that stuff is still around. And actually, being European, all of these ideas are so much a part of our culture — Freud, and all of those ideas come from Greek philosophy. That is the underpinning of the film, and it is something that Deborah and I discussed when we first met.

PR: Swimming Home is a metaphorical film which doesn't set out to clearly explain itself. The responses to the film suggest some people are responding to this, while others are pushing back. But as human beings, we are conditioned to want to understand. A film like yours gives the audience space to enter the film and be proactive participants in creating their own understanding.

JA; You're right, and I'm quite surprised by some of the fury about the film. Some people get really angry, and, of course, I'm taking 90 minutes of your life, which I accept is a big imposition. But if you wipe that away, I find it quite staggering why you are so angry about something that's obviously trying to just open something up and not give you all the answers.

|

| Swimming Home |

I went to see a play recently that was just all over the place, but in an interesting way. I looked around, and I thought, 'Who are all these people? They seem to be enjoying it; they're not questioning it.' We accept the abstract nature of music, but we've become quite conservative with our storytelling, in our need to have it clearly be about something.

[…] I think because of the crises everywhere, we need to try and make sense of the world. And we have so much information now, that we try and make sense of everything, but we just can't. I don't want to be like, oh, in the Sixties or the Seventies and all that stuff, because I don't believe human beings fundamentally change that much. So, it's not that I'm looking back with rose-tinted spectacles, but I am surprised by some of the critics, and why they are so bothered by something that doesn't quite give you all the answers.

Often, when you try and explore new ideas, and I don't think there are new ideas in this film at all, but if you try and explore new ways of playing with ideas, then it becomes problematic.

PR: What complicates matters is that we habitually imagine a version of the film beforehand. The challenge is then being flexible enough to shift our expectations and judge the film on its own merits and with the filmmaker's intentions in mind.

JA: We're all guilty of it and I do it all the time — it's part of human nature.

It took a long time to make this film. People were asking, "What is it? Give me a comparison." I was like, "I don't know. I'm just trying to make a new film. It is what it is." They asked "Is it The Biggest Splash meets…"

|

| Swimming Home poster |

So, it is something we try and do and, interestingly, I keep reading people saying I'm trying to be [Yorgos] Lanthimos. Really? If I wanted dry Greek humour, I would have had dry Greek humour. Or they say, "He's trying to make an erotic film, but it's not erotic." Well, I would have put more eroticism in if I wanted it to be erotic.

Nadine Labaki, an Oscar-nominated filmmaker, and winner of a jury prize in Cannes, knows her stuff. She said, it's just that they're trying to find a box to put me in, and they know they can't find one. So, you just have to go with it and that's fine.

Since we showed it over a year ago in Rotterdam, I've found that when I've shown it in cinemas with audiences, there has been more of a conversation. You write about film, and you know that when you have to write about something, you obviously have to fix it. And I don't think it works for this film.

I saw Athina Rachel Tsangari's Harvest recently. I loved it and one of the things that it did was hover above something but not land. I thought, 'Oh, yes, you tricky little bugger,' and about three quarters of the way through the film, I realised she'd taken us somewhere, and then she'd just move off somewhere else. She's just moving us around, and I enjoyed the ride, but I found myself trying to fix it.

I'm a great lover of the American comedian Bill Hicks. He used to say it's just a ride, man. Stop trying to make sense of it. Stop trying to tie it down and tell everybody this is important. That's my belief in humanity. We're just here for a little bit, and actually, films, like all art, is partly our residue. It's what we leave for the future and people can make of it what they want — it's just a mark.

Swimming Home is released theatrically in the UK by Anti-Worlds on April 25. A digital release from Bohemia Media will follow in May.