|

| Cube |

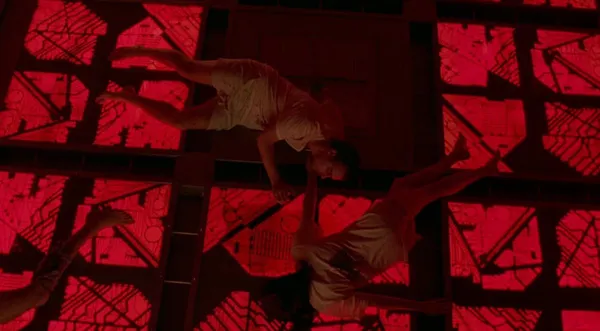

Canadian director Vincenzo Natali's Cube has become a cult phenomenon, now restored in 4K by the Canadian Film Centre. A precursor to the Saw franchise of deadly games, Natali's sci-fi horror pitched the premise of strangers waking up in a giant cube structure, made up of over 17,000 cube-shaped rooms. To escape, they must navigate the labyrinthine structure and avoid triggering the deadly traps contained inside each cell. At this year's Fantasia International Film Festival, Natali was bestowed with the Canadian Trailblazer Award.

The filmmaker's work has not always been met with popular appeal, but he has never sought to repeat himself. After Cube, he directed two feature films in quick succession, beginning with the sci-fi espionage film Cypher (2002), before merging sci-fi and surrealist comedy in Nothing (2003). Then, he shifted back towards Cube's darker tones, coupling sci-fi with horror in Splice (2009), and since then he has held an interest in supernatural horror with Haunter (2013) and In The Tall Grass (2019), an adaptation of Stephen King and Joe Hill's 2012 novella. On the small screen, Natali has directed episodes of Hannibal (2013-2015), The Strain (2014-2017), Westworld (2016-2022), American Gods (2017-2021), and Guillermo Del Toro’s Cabinet Of Curiosities (2022).

Connecting with Natali virtually from Fantasia, I found myself relating my first encounter with Cube - on a VHS recording off the television. Immediately, you can sense Natali's humility, slightly unsure how to respond, perhaps a little guarded, preferring to downplay the way his classic film has personally struck a memorable nerve with audiences. It means our conversation has an organic beginning, that will lead into a broader discussion of the "digital rabbit hole," why fear impairs Hollywood's creativity and the need to be weird.

Paul Risker: Getting lost in the nostalgia of VHS, scouring the television guide for films to watch and record, reminds me of how much viewing habits and accessibility have changed.

Vincenzo Natali: It has changed, and it's changing on every level too, because it's changing in the realm of your choice as a viewer and as a consumer. It's also changing in the way that people are choosing to make films. So, there's a tremendous flattening of culture that is happening because of that - under the guise of giving the consumer what they want, but as we well know, the consumer does not know what they want. In fact, it's usually best when they're introduced to things that they don't know they want, but they need.

I know that's the case for me. I like it when I'm recommended things that I know nothing about, or on the face of it, wouldn't be particularly interesting to me. But because of the person who knows me and is making the recommendation, I trust that it will be great. I don't think there's an algorithm for that.

PR: The evolution of cinema has at times been unexpected because a filmmaker dared to take a chance and believe. If the audience doesn't know what they want, then neither does the industry. However, given film economics, cinema is often averse to spontaneity.

VN: Yeah, that's why there's a proliferation of remakes, sequels, and reboots. I'm not saying you can't have a good sequel or you can't have a good reboot, and those things can't be relevant to the moment, but it's much more difficult when you're working with material that was written for another time. You then have to find a way to import it into the present. I'm much more interested in things that are created for now, and the world today is very different to what it was even five years ago.

PR: Looking back to Cube, could you have envisioned it being the start of not only a franchise, but the beginnings of a career that has spanned the big and small screen?

VN: I just feel incredibly lucky. On one hand, I would never have thought that Cube would have the life it has had -having this discussion all these years later [laughs] or that it has been restored.

It was almost a home-made movie. It was made with friends, through film school. It didn't go through the conventional pipeline that movies normally go through to get made.

Having said that, I confess that when I first had the idea for it, I knew it was special because I know science fiction. I know what's out there, and I know how hard it is to come up with an original idea. I genuinely feel that Cube was very original from the moment we conceived it and I recognised that at the time.

That was actually why it was hard to get made, because at that time there weren't a lot of single-location movies. We took the commercial route, but we didn't exactly go to the studios because we were so young. Instead, we went to the kinds of companies we could go to. There was always a smidgen of interest, but they always said, "Oh, this is a short film, it isn't a feature." It was only because I had the good fortune to go to the Canadian Film Centre, which is an advanced film studies school here in Canada, that it got made. I'm not sure that it would have been made any other way - I was insanely lucky. There's always a tremendous amount of serendipity involved in these things, so, I appreciate that I lucked out, and I thank the cinema gods that I was able to do it.

PR: Speaking with Joachim Trier, he said you have to be allowed to make a film. The perception is that what we see onscreen is the filmmaker's intention, but any film is a series of compromises.

VN: The art of directing is the art of compromise, but it's when the compromise is not less than your objective. When the compromise is additive, that is the art of directing.

If you gave anyone infinite time and resources, they'll probably make a good movie, eventually. But give them 20 days, as we had on Cube, and a very limited amount of money and not everybody could. I'm not saying I was great, but not everybody can do that. I failed constantly, but I learned and over the years. I do believe I've gotten better and more receptive to obstacles that present themselves when shooting. It's very Zen, but you learn to go with the resistance. If you are pushing against an immovable object, you're screwed. Instead, you adjust your plan to incorporate the immovable object and to perhaps take you higher than you had planned in your mind when there were no obstacles.

I often find that the best ideas and the best things about the movies that I've worked on, and I'm sure this is true of everyone, come by accident. And very often, they come out of a problem that at the time was something that seemed like it could be catastrophic.

It's a hard thing to learn, and I'm still learning, but I have become more receptive to that approach - and you don't have a choice when there's so much money, so much technology... Directing is like painting with a 12 foot paint brush. There's so much distance between you and the canvas that you have to know how to operate it, so that you're still getting what you want on the canvas.

Not to beat on James Cameron, who I admire tremendously, but I think his earlier films are better than what I would call his animated movies that don't have those same restrictions. They do because everything has restrictions, but I'm willing to bet it's not at the same level. His restrictions are about how far he can push the technology. I don't think that's in some ways as artistically fruitful an environment for someone like him, who is very smart, and you feel it on the screen. Aliens, you feel the sweat and the pain [laughs]. What was it he said? He never wanted to experience that again, but it made it a good movie.

PR: Was Terminator 2 at the threshold of how far you can push technology without losing something?

VN: I don't want to disparage those movies too much because there's a lot to recommend. I cry for the animators because I can feel the sweat and effort that goes into it, but I feel a number of directors I admire have gone down that digital rabbit hole - like Robert Zemeckis and George Lucas. It's just a little too comfortable, and I'm pretty sure they're doing a lot of their directing from their couch or on Zoom.

There's an art to directing animation, but it's very difficult to replicate the visceral experience of being in a real place in an animation studio. Like Dune. I feel they shot that in a real place, and that adds so much to the film. And I'm sure that's difficult and unpleasant. I'm sure it's also fun, and I'm sure there are times when it's not - there are flies, it's hot and people get cranky and difficult, but that births this thing that feels visceral and real. I think that's what I'm getting at, especially when creating fantasy. Of course, all films are fantasy, but we're talking about creating a world like they do in Avatar (2009-) and Dune (2021-). There's an advantage to incorporating reality into your fantasy to ground it, and to give it that verisimilitude, as opposed to something that is created on a computer hard drive.

PR: How do you look back over your body of work and compare and contrast the individual films?

VN: To my own detriment, I always try to do something different with each movie. Not that there aren't threads, one of which is they're all low budget, which means often they only take place in one or two locations. But I want to try different things. I don't want to remake Cube, and I don't want to remake Splice. I wanted to do a comedy, a spy movie and a ghost movie. I have no desire to make a story about real life in the literal sense. I always want to work with elements of the fantastic but in different ways.

As somebody who enjoys these movies, I feel beholden to try to mutate the genre and not just replicate something that already exists - I want to try to be additive and take it somewhere a little bit different. So, I have a certain amount of pride with my body of work. There were one or two opportunities I could have taken that would have fielded a more generic kind of movie, but I just couldn't do it.

PR: I can't recall where I read this story, but in the Seventies Peckinpah was offered a big budget film to direct, and he turned it down. Instead, he directed the war film Cross Of Iron in Europe, where he ran out of money and yet was able to still craft a brilliant ending.

VN: I love Sam Peckinpah. I just saw Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia on film at a packed movie house, literally a couple of weeks ago in Toronto. It's such a good movie, and it's made by a madman. It's made by someone who doesn't care, who is fearless and wants to blow everything up, figuratively and literally. And it's the work of an artist.

I don't have any affection for the western as a genre. There are westerns that I like, but I like all of Peckinpah's westerns and that's because he's breaking the rules of the genre. Or maybe more specifically, it's very personal. You feel that his films are infused with his personal fetishes and obsessions, and he obviously had some deep moral conflict that he was battling with. So, yes, I think he's a good north star to have, minus the cocaine and alcoholism.

PR: You've spoken about the digital rabbit hole, but from 1997, when Cube came out to the present day, how do you perceive the trajectory of fantasy, science fiction and horror cinema?

VN: Like everything in the world, I think it's bifurcated - there are two paths. There is the independent world that continues to do really interesting stuff and then there's the studio world, that is not always, but is generally doing some regurgitation of something you've seen before. I confess that I miss the time that Cube came out because there was a vital independent film scene that was lucrative - it made money, but now it doesn't really. It has become marginalised where people have to make money without getting paid or paid very little. And the movies don't make much, even though they're great.

I saw this fantastic Canadian film called In A Violent Nature (2024) a little while back at a film festival. As soon as I saw that one, I thought it was special and, sure enough, people gravitated towards it. But it was made for nothing, and it's such an original piece that you won't see it coming out of Hollywood. You'll see it now because maybe Hollywood will do their version of it, but even then, they won't be able to because it does things that scare them.

So, I think we're in a more bifurcated and divided world, unfortunately, but there's always hope. I feel like Fantasia is a signpost for the future because we need the weird, especially since the algorithms have homogenised everything. It's weird if you actually go into the etymology of the word weird - it means fate, from the German word wyrd. So, I think our fate [laughs] is to become weird.