|

| "First Nations people in Australia weren't classed as human beings" - Victoria Wharfe McIntyre |

Interviews between one side of the planet and the other are always a curious experience. It’s lunchtime where I am in Scotland, even if the sky is dark with rain. In Australia it’s late, and Victoria Wharfe McIntyre has surrounded herself with lamps to try and brighten up a book-lined room which doesn’t have any bright overhead lights. The effect is somewhat Gothic, but she’s not here to talk about a Halloween film. The Flood deals with a different kind of darkness, and the horrors it portrays are all too real.

In Forties Australia, the conscription of indigenous men left their female relatives and children with even less protection than usual. Victoria’s film explores the way that some white Australians took advantage of this to split up families, isolating individuals still further and forcing them into slavery. It centres on one woman, Jarah (Alexis Lane), who tries to resist, and on the events that occur after her husband Waru (Shaka Cook) returns home. One of the things that makes its interesting is its structure, which follows more complex, cyclical patterns rather than the linear driving narrative favoured by most of today’s filmmakers. I ask Victoria if this was influenced by the different storytelling strictures of the First Nations people she was working with.

|

| Waru goes looking for justice |

“Well, we definitely made the film very much in collaboration with indigenous people,” she says. “We had elders on set continually and I was always talking with them. And it really evolved as we made it. Obviously it was fully scripted.” She pauses. “I think I just am that way. I'm a bit bored with the same structure we’ve always had. And it's quite deliberate at times because I want people to get shocked out of the position that they might be holding, witnessing the story as it unfolds, and to be suddenly taken aback and maybe at those moments, think about where they're at in this story and how they're feeling at the time. So yes, it's deliberate, but also intuitive.”

It’s also film which focuses on community rather than on one central protagonist.

“Yeah, well, I feel like that's how we exist in a community, in groups. We're in each other's lives in all kinds of ways. And I guess the film just really reflects that.

“I see it as telling the story, or a story, of our nation's history, visibly. It's not an indigenous story. It's not an invader colonialists story. It's a microcosm of where we still are today with our race relations and where our society is sitting. So yeah, it's a collective story. And still we travel through the Banganha family, we really are sticking with them predominantly through it, but we get to see and then have a deeper understanding of the characters that are around them.”

Something that I found interesting was her decision to show some of the characters wearing sunglasses at the end, which really makes it clear that this is not ancient history, but something which happened within living memory and whose effects continue to be felt today.

“Yeah, totally, although they are period sunglasses, not modern sunglasses as such. But yeah, it's that stylized, I don't know, I guess an attempt to be a bit cool as well, which brings in the modern era exactly like you're talking about and really, I mean, it is so relevant, still, not only here but all around the world where First Nations cultures and people are still grappling with the land as it's been altered, whether it be 200 years here, or 400 or 500 years in America or, you know, all around the world. So it's a human story.”

|

| Ready to resist |

It made me think of the American film Mudbound in the way that it addresses the war, and the way, that having fought side by side, it was very hard for people of different races to go back to the hierarchical structures they lived in before that.

“Oh, sure. I mean, at that time, First Nations people in Australia weren't classed as human beings. They weren't even recognise legally as such. I mean, that's our grandparents. It's just so relevant, and so current. Particularly those kinds of stories about the war and indigenous soldiers and the treatment they received when they came home. The injustice of that is really the kernel for this film. I made a short film about that, Miro, in which Alexis Lane, who plays Jarah, had a small role. And then she was just so incredible in that film that I wanted to write a feature to have her in it, to be able to get into her talent, and The Flood came from there.”

Were there stories about real individuals that went into the film?

“Oh, definitely. Everything that happened in the film has happened. Particularly so the massacre scene, and what Waru goes through. Without giving anything away, what happens to him happened to a man right here where we shot the film, in Kangaroo Valley. So it's really echoing the truth. But of course, not all of that happened to the one family. It's information about different people's experiences that went into the film.

“Sadly, it is mild. The things I actually wanted to put in, we probably wouldn't even get a single audience member. And it's really interesting. The elders on set were always pushing to go harder, harder. I mean, the film is brutal, in part, but they wanted it to even go further than that. That's their experience.”

Is it one of those things where often with minorities, when you show a less extreme version of what they have to deal with, other people actually take it in better and are more willing to believe it?

|

| Fighting side by side |

“Sure. You've got to keep the audience with you. I mean, we really fly close to the wind in this film. It's not that it's gratuitous, the violence, the film, and it's not even particularly bloody, or, you know, we don't see so much of that. But it's so raw and real. And that's what people find hard to digest, because when you're watching it, it sinks in.”

It’s a particular challenge to show sexual violence, which is an important part of that history, without being exploitative. There’s a scene midway through The Flood which depicts this and whilst it doesn’t involve any visible nudity, we get the message very clearly. How did she approach staging that?

“Once I saw the wide shot of that room and the actors in the moment it was like, okay, this is one shot scene and there's going to be no cutaways,” she says. “We're just going to feel like we're in there with her and there's no escape. There is no escape for anyone who is overwhelmed physically and experiencing violence of any kind. There's no escape. And there was no escape for indigenous people when colonisation happened, it's just how it is. So I wanted us to have that experience.”

It’s also interesting because there’s a young police officer present who's not participating but doesn't know what to do about it, even though he knows it's wrong. Did she want the audience to relate to that character, to feel like witnesses who are close to those events but can't actually intervene in any way?

“Actually I never really thought about it like that,” she says. “I can see how you can read it that way, for sure. For me, I think he's just a representation of authority that is controlled by the vested interests around authority. To me, even the political landscapes that we live in, I don't really feel like it's the politicians who have the power. It's the the interest groups and the forces that act on the politicians that have the power. In this case, the Mackay family are the power brokers. He's an authority figure who is just responding to them as the authority rather than taking ownership himself and doing what is right.”

|

| Dreaming of another world |

Speaking of authority and power, the film is also interesting in the way that it addresses the complicity of the Church in splitting up families and covering up abuse. Is that something that perhaps it's easier to do today, now that people are starting to question the role of the Church in Australia more widely, and how it's affected a lot of people's lives, than it would have been a few years ago?

“I think so.” She laughs. “I think it would probably have to be, because the Church has really had its claws in the power systems of the societies all around the world, in the Western world anyway. I think there has been a fall from grace to a certain extent. The general public is more willing to go, yeah, a lot of wrong has been done under the auspices of the Church. And it's perhaps really time for that to be more fully owned them even what it has been to date,”

There is, however, an idea in the film which many Christians will relate to strongly, and that’s redemption. That’s where it departs from standard western or revenge movie tropes and does something more interesting. What prompted her to take that route?

“I think fundamentally, as a human being, I am into reconciliation and redemption and understanding,” she says. “When you understand someone's experience, you can understand why they behave the way they do. And when you can separate yourself from it enough that it's not personally about you, you can see who they are and where they're coming from. And from that space, you can actually find forgiveness through that understanding. And so long as that person is owning where they're at and what they've done, then I think you can move forward.

“That's really what the film, for me, is about. In this country, it's about reconciliation between the people of this land now. And, you know, we can only move forward together, through looking at the truth of our history and our past and owning that. And the thing that I always find so incredible about the First Nations people that I know, and I think more generally than the people that I personally know, is their willingness to extend the hand of friendship and actually move beyond the pain of the past. In a way, we're the ones who are stuck – the non-indigenous people are stuck with our guilt and a whole range of other things. So we're the ones who aren't moving forward. And this feels like talking about, hey, we can have the strength to look at the truth and then find peace together.”

|

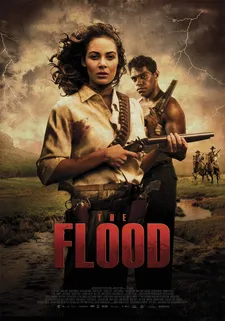

| The Flood poster |

The use of flashback to show us how one character was taught prejudice and hate perhaps suggests that that toxic culture damages people who grow up within it, as well as damaging others.

“Oh, for sure. Violence and hatred and prejudice begets violence and hatred and prejudice. If you're raised in that space, that is just a normal space. It's not until you're presented with new experiences or alternate worldviews that hopefully you come to question the belief structure that you're raised in. Again, that's all part of where the film is coming from, to, to encourage that, that looking beyond the mindsets that any of us might be in at any time.”

Recently we've been starting to see more stories addressing these issues, addressing the interrelation of cultures in history and through to today. I ask her if she sees her film as part of a conversation that's opening up within cinema and the arts more generally.

“I would be honoured to think that this film is part of that conversation,” she says. “I mean, that was the intention behind making it. We haven't really had a film like this in Australia before, where the First Nations people are given such agency onscreen, where they are the heroes, where they're the keepers of wisdom, where they're the spiritual force that carries us through the entire film. And then they're the ones who are waking us up. And I really believe that the Australian First Nation people, much like the Native Americans, or, I mean, all indigenous cultures, have this incredible grounding in spirit and consciousness, and they’re our teachers. This film is saying: look at this wisdom on the screen, look at this compassion, look at this understanding and look at this vision of moving beyond where we are.”

Is it something that she sees herself returning to as a filmmaker, are there other projects that she has coming up now?

“I think with my short film Miro and now The Flood, I feel like I've said that in those two films, so I'm ready to move on to my next social justice crusade,” she says with a smile. “I'm not quite sure which will be the next film but I've definitely got a supernatural a thriller built on the Cassandra mythology, sort of about believing women when they come forward and speak. I think we still very much need that in the world today. And a sort of a science fiction film that's got the fundamental premise of ‘Don't screw up Planet Earth because there's no other planet we can go.’ We can talk of Mars and this and that but there's no viable alternative so we really need to protect the planet we're on now. But telling those stories, you know, in an entertaining and a bold and fun way, I'm ready to do something a bit more fun. I’ve traversed the darkness now.”