|

| Freddy McConnell |

Not so long ago, the idea of trans men getting pregnant and giving birth was treated by the media as pure sensation. One major newspaper actually ran three successive stories within two years, each with a different subject, each claiming to be abut the first man to do it in Britain. By the time Freddy McConnell came to it, the picture was thankfully changing. He might have had the option of enjoying a quite, peaceful pregnancy in relative obscurity, but events were destined to change all that. In the meantime, he made a big decision: he was going to find somebody to film his journey.

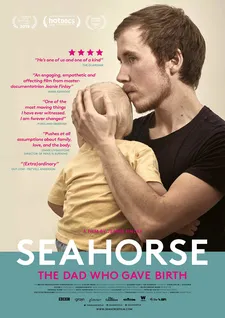

The result was Seahorse: The Dad Who Gave Birth, directed by Jeanie Finlay. Freddy and I recently arranged to talk about it. Sitting back in his spacious living room with the clear light of the Brighton coast bouncing off the white walls, he looked wonderfully at ease, relieved of many of the stresses we see him contend with in the film. I ask what it was that persuaded him to make it.

|

| Freddy with his pregnancy scan |

“It’s not as simple as wanting to live a quiet life,” he says, reflecting on the alternative. “I want to be in control of what I share and don’t share. I want to be in control of telling my story accurately, which isn’t something that I think trans people have been able to do, for all sorts of reasons, over the centuries. As a journalist I felt that I could try to show that you can do things respectfully and humanely and collaboratively without it diluting a story. You can have nuance and specificity and you can highlight the things that are actually universal and relatable, and it makes it a better story. It doesn’t need to be sensational.

“I thought for a long time before deciding to find a filmmaker to work with. I spent a long time getting comfortable with the idea but then, as a video producer and someone who’s loved documentary for many years, I thought it could be an amazing opportunity to tell a story in a different way. I was very worried about my privacy while I was pregnant. I was very dysphoric and anxious and struggling but I knew that there was this pact at the beginning of the process that meant that the film was a secret while it was being made and it wouldn’t come out for about a year afterwards .I wanted to tell my story but I wanted to do it in my own time and on my own terms.”

With this in mind, how did he go about finding the right person?

“I had a conversation with my colleague at the time, Charlie Phillips [at the Guardian], and he decided to speak to a few directors that he knew and see if there was any kind of spark, and there was with Jeanie, straight away. She described what I wanted to do back to me immediately, translated into director-speak, and I was, like, wow! Then the production company, Grain, who’ve been behind Oscar-winning and nominated films “ – he references Learning To Skateboard In A Warzone (If You’re A Girl), which I note is a personal favourite, and he mentions having volunteered Skateistan, the charity it focuses on – I brought these people together and that’s how it went. I knew Orlando [von Einsiedel, on of the producers] before but I didn’t know Jeanie.”

I ask if he felt that he was in control throughout the process and he suggests that it was more complicated than that.

“I brought the thing together and I set some ground rules, or a set the tone for the project, but really I wanted to find a filmmaker who I could give that control to at a certain point, for telling the story, because I didn’t want that to be my responsibility, because I was busy!” he laughs. “I obviously worried about it still because you’ve got to have trust and you know how these stories have gone wrong so many times, but I didn’t question her too much about the process. I got the feeling early on that she was a very serious filmmaker and storyteller and that for her the storytelling was all-encompassing. So even when I didn’t know what was going on or I was really stressed, I had this deep trust that it would be okay.”

|

| Freddy by the seashore |

He let [Jeanie and editor Alice Powell) make the big storytelling decisions, he explains, partly because he felt that the film needed a cisgender lens – a sort of translation for viewers with no familiarity with what it means to be trans. With their help, he felt confident that it would make sense to a general audience and he wouldn’t just be speaking in jargon.

It’s one thing to sign up for something like that at the outset of a pregnancy, however – another to stick with it when hormonal changes make one’s emotional reactions much more unpredictable. Were there ever moments when he doubted his ability to go through with the film?

“I really struggled,” he acknowledges, and observes that it was difficult to separate feelings about the film from the rest of what he was dealing with. “I consistently checked in with myself and searched around for that feeling that made me do it in the first place. Is this going to be a worthwhile endeavour? is it worth the stress I’m feeling right now? What were my original goals – did they still feel present and valid? They always did.

“My mum was very helpful on that score because she’s very strong and she’s definitely of that tough love school of thought. Obviously it wasn’t her idea and she wouldn’t have forced me to do anything – she didn’t have that level of control – but she was a very helpful vice saying ‘Come on, what do you need? Let’s do this. We’re doing it together. It’ll be fine.’ Quite pragmatic!” He smiles.

I remark that from what we see in the film, it seems that he had really good experiences with the medical staff who helped him with various aspects of the pregnancy. Was it like that throughout?

“Yeah. I got really lucky, I think,” he says. “The clinic was great, but then clinics tend to be customer-oriented. What was really special was having my midwife Jo, who I don’t think is in the film, but she’s a local midwife – she was actually the midwife for my sister – so she became a sort of guardian angel. Everyone else that I encountered, apart from one person at a local hospital, was great. It wasn’t like anyone had special training or had ever encountered a pregnant trans man before, but Jo laid the ground for me a lot of the time, making sure that people knew about my situation and were safe. Other people were just being good people and caring and having an open mind. And then maybe there was an element of – well, I still basically am read as a cis man because of how I look and sound, so I think I probably got a bit of male privilege from there, being taken seriously and taken at my word and so on.”

There’s a moment in the film when Freddy pauses to reflect on how pregnancy would be perceived if it was something that most men could do. When I raise this he says that the scene makes him cringe because it’s something that shouldn’t be occurring to him for the first time, in his thirties. He still thinks it’s important though.

“It’s not that what I’m saying is profound, but it’s like yeah, here’s this guy – who, yes, was socialised and raised female until his early twenties – and it’s only just dawning on him now? What this all means. It’s things like, I wonder about cheese and sushi and can I eat that, and I don’t know, and it’s like ‘oh, because of sexism!’

|

| Seahorse: The Dad Who Gave Birth poster |

“It’s an important point, but I also felt quite uncomfortable about my class and my race and all that, that obviously made things easier for me than they might be for other people. I wondered if I was the right person to be seen as a role model or pit myself out there, because actually my experience probably isn’t representative even for other trans men going through this.”

Might it help other trans men, though, to see that it is possible to have such a positive experience?

“Oh yeah. Definitely. I had two motivations, one about showing how you can tell a trans story better and one about sowing trans men this is possible – don’t believe what the doctors are telling you! Because they’re still telling you that testosterone makes you infertile and there’s no evidence of that. Really the best way I can get that message out there is to make a documentary about my pregnancy, which seems very bizarre, but yeah, it was as simple as that.”

We talk abut how the film deals with all the small ways in which trans men’s experiences are rendered invisible, such as when Freddy has to alter forms, and one particular scene near the end when a conversation about pregnancy between his own friends and family members focuses entirely on women and the camera closes in to show the effect this is having on him.

“That scene is so powerful,” he agrees, “and I had no idea what was being captured that evening. When we went into filming it it was just supposed to be a nice dinner party. I thought it probably wouldn’t be used because it was bland. It wasn’t Jeanie that time. It was her assistant cameraperson and they were using a long lens so I couldn’t see them creeping in like that on me. I had no idea that the scene would convey the reality of it. I’d got so used to not being able to convey why that was so uncomfortable, and obviously those people are all very well meaning. My auntie was there, and the woman who was singing the Dennis Rousseau song has since become an even closer friend of mine, having been a very close friend of my mum’s. That scene, when she watched it back, was very painful for her to see. it was quite an amazing moment really, but it’s exactly what I hoped the film would achieve. It’s the sort of this that you can’t make happen, you just hope it’s going to happen, when stuff that’s so hard to put into words is captured and then people sit in a dark room and don’t have to argue or debate anything, they can just experience it like I’m experiencing it. It’s empathy.

“I just hope as many people see [the film] as possible. I hope that trans people, especially young trans people, see it, and that whatever they need to take away from it, whether it’s practical advice or a sense of hope, they find that; and I also hope just everyone sees it!” He laughs. “Not everyone can meet a trans person. This is our attempt to replicate that experience... Maybe it will do a little bit of the job that needs doing, towards making trans people real in people’s minds. People they are about and actually empathise with and not just a talking point.

“I had a middle aged man come up t me after one screening and say ‘My daughter said I should come and see your film. I was very reluctant. I’m so glad I did. It’s changed how I understand it all.’”

Since he completed work on the documentary, Freddy has been involved in a highly publicised court case, petitioning the state for the right to be listed as a father on his child’s birth certificate so that his child’s privacy will be protected and there will be a decreased risk of prejudice associated with having a trans parent. Having been rejected at the High Court just days before our interview, he’s no planning to go to the Supreme Court. I ask how this is proceeding.

“Obviously the High Court judgement was disappointing,” he says, “but as I understand it, these are the kinds of cases that are often destined to go all the way from the start. I didn’t think it was going to be really big when I started out. I think it’s fair to say that I really did just think I was fighting for my own child’s birth certificate to be accurate, and then as the case developed we realised just how utterly trans parents had been left out of the equation at every step. Every piece of legislation that was coming through that could have acknowledged us, didn’t. Then, also, just how the Births and Deaths Registration Act is so outdated and actually doesn’t treat any queer parents equally, because these definitions of mother and father are so biologically essentialist and archaic.

“I think most people, if they really understood what that legislation says and does, would be pretty shocked. Like with surrogacy, where the surrogate’s husband is the father even though he has no genetic link to the child – all sorts of bonkers stuff. So when I realised the stakes, I made peace with the idea of seeing it through no matter how long it took, and so that meant tat the judgement was disappointing but not surprising.”

And is he still enjoying fatherhood as much as he was at the end of the film?

“Yeah,” he says with a shy smile. “I’m really lucky, I suppose, that I really feel fulfilled by this role and would happily just be a full time stay-at-home dad!” He laughs. “It just feels like a real privilege, you know? We have great fun. We’ve been exploring local woods.” He pauses, glowing the way that new parents sometimes do. “It’s hard to put into words but it’s great.”

Seahorse: The Dad Who Gave Birth is out on Digital and On-Demand on 16 June.