|

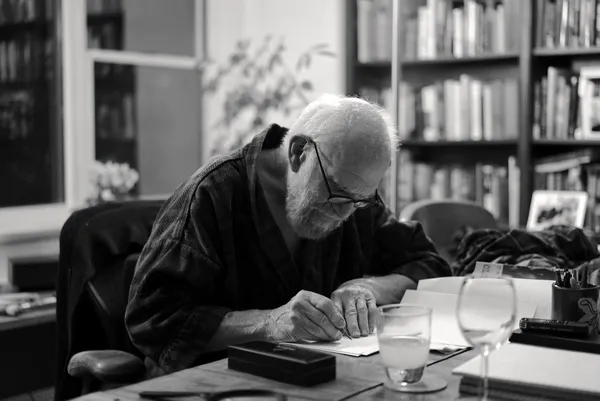

| Oliver Sacks: His Own Life Photo: Glasgow Film Festival |

Ric Burns is well known for his historical documentaries and explorations of the lives of famous figures. This year's Glasgow Film Festival was fortunate enough to feature the UK première of his latest film, Oliver Sacks: His Own Life, a moving portrait of the neurologist and author made during the final few months of Sacks' life and completed after he passed away from complications of liver cancer. Ric agreed to answer some questions about the film and I began by asking him how he first became involved with the project.

Ric Burns: In early January 2015, I got a call from Oliver’s wonderful editor and chief collaborator, Kate Edgar, through a mutual friend. I had never met Oliver, though of course knew his work, and didn’t know Kate, either. She said Oliver had just received a mortal diagnosis, had perhaps six months to live, and wondered if we would come and film him. So we did, and a few weeks later, in February, began filming in his apartment on Horatio Street in the village.

Jennie Kermode: Your work has explored many aspects of American culture and history. Did you see this as an opportunity to explore the overlooked, outsider stories of Oliver himself and of the patients he worked with?

RB: It was certainly an opportunity to explore the stories of people outside the mainstream, and too often marginalised – including Oliver himself, which was his lifework. The project of deep empathy, the exploration of the interiority of other beings, and the rendering of that experience as narrative – the project in short of Sacks’ whole career – had the effect of showing, ironically, all the things we share in common, across differences that from the outside appear enormous, and that of course in many ways are.

JK: Watching the film, one gets the impression that Oliver was very enthusiastic about participating in it. How did your first meeting about it go, and to what extent did he take control of how his story was told?

RB: Despite the diagnosis of metastatic cancer of the liver, he was completely undiminished. Our first filming went on for five days, 12 hours a day, Monday through Friday. He was 81, had just completed but not yet published a very candid memoir, and very much wanted to make sense of his life, for himself and others, as he approached the end, and it was immediately apparent that two intimately related narratives would be unfolding: the story of Oliver’s life, as told by himself (abetted by two dozen others who knew him well); and the story of a man facing death. Oliver was a man tremendously absorbed both in himself and in other people, in equal measure, and also a person at once very guarded and completely transparent – and these were qualities immediately on display.

JK: Your work with your brother has demonstrated that there is an audience out there for thoughtful, informative and detailed documentary cinema, but is it still challenging to get this kind of work funded?

RB: Funding is always a challenge, of course, but that’s probably a good thing: it means you have to prove yourself, and prove the potential not only of your topic but of your approach to it, each time out, and that keeps you from ever being able to dial something in. The most important capital for a project is the genuine excitement and interest you feel about a topic, and if that’s real, it will be communicated to others – in pitches, proposals, scripts, assemblies, etc. Those don’t sell themselves, of course, but most of us working in this corner of the filmmaking world find, I think, that the things that excite and interest us will excite and interest others – and under those circumstances, it’s usually possible to find interested funders.

JK: You recently looked at the other end of the cultural spectrum with your film about the National Enquirer. In a society fascinated by celebrity scandal and sensationalism, do you think enough attention is paid to complex intellectuals like Oliver?

RB: Absolutely not, which is criminally shortsighted. The drama and richness of the inner lives and careers of women and men who have devoted themselves to exploring the farthest reaches of daunting topics is boundless, and inspiring, and incredibly illuminating and enriching for anyone who bothers to look. Oliver’s story touches on so many questions – consciousness, mortality, neuroscience, evolution, chemistry, biology, ethics, what it means to live a good life. It’s hard to understand why American culture has tended to demote or undervalue work of the most enriching kind like this.

JK: There are some wonderfully funny stories in the film. Did you have more material like that which you were unable to include?

RB: There are another three films worth of material buried in the 90 hours we shot with Oliver, and the interviews we did with so many people who knew him, and his work, well. And just when you thought you had him figured out, he would surprise you with an insight, or a connection, or sudden expression of joy, humour, indignation, warmth.

JK: How did affect you and your team to learn that Oliver was dying?

RB: We knew from the start that he was dying of cancer, and that fact of course influenced everything about our interactions with Oliver. We wouldn’t have been there if he wasn't dying, to put it bluntly. What was most moving was his tactfulness and delicacy and at the same time complete openness about the fact that he was dying. He didn’t shrink from acknowledging it, he grasped the pain and difficulty it imposed on others as well as himself, but he was enormously courageous and resourceful and determined to live his life in the fullest possible way, to the very end. And he did. Which was inspiring beyond words.

JK: How do you feel about the film being shown at the Glasgow Film Festival?

RB: I can’t begin to say how honoured and thrilled we all are that the film is being shown at Glasgow. The Burnses of course are Scots; though I must say it came as a mortifying shock to be told when I was ten by my grandmother that we were not, as I fondly wished, courageous highlanders, but instead horrible quisling lowlanders in league with the English. I’m not sure I’ve recovered from the shame.

JK: Can you tell me a little about what you’re working on now?

RB: A bunch of things. A big film about Dante. A film about African Americans on the road during the era of Jim Crow called Driving While Black, which is really about the history of race, space and mobility in America. A new episode in our series about New York, chronicling the city since 9/11.