|

| Caitlin Custer in The Mortuary Collection Photo: Glasgow Film Festival |

The first thing Ryan Spindell does when I connect with him on Skype for our scheduled chat is to apologise for having a boring office. It’s painted white with a Venetian blind over the window; a shelf at one side looks as if it’s thinking about spilling books onto the floor. He’s envious of the wall of books behind me in my study. I suggest that he get a poster with books on it to sit in front of whilst he Skypes, and his reaction makes it clear that we’re going to get along.

Ryan is the director of The Mortuary Collection, one of the films selected by the Frightfest team to appear in their section of this year’s Glasgow Film Festival. I admit that I approached it with some trepidation, having a queue of over 50 films to get through and afraid that I would now have to review a lot of separate shorts as well, but it’s not like that. This is something rather more old fashioned, a central story with short stories woven into it, very much a complete work. Was t always planned that way? I ask, or did it begin with ideas for separate shorts?

|

| The mortuary is always open |

“It’s a little bit of both,” he says. “I started out as a director but then when you come to Los Angeles you have to write a feature, and so I kind of, like, became a writer out of necessity, and I was doing writing projects for companies that I was really not liking. There was one project in particular where the only not I kept getting back was to make it more teen, make it more teen! And it was a movie set in a high school so I was, like, I can’t make it much more teen! And so I was just sort of frustrated, and I had been watching a lot of the Amicus anthology movies at the time, and I was just sitting there and I was like, ‘What’s the movie that I want to see the most, as a fan? What’s the format that I love that I don’t see anymore?’

“I was thinking about the whole anthology format and I thought ‘This is a format that needs to come back.’ I think people have kind of forgotten about it. There’s been a few that have come along that haven’t been so great, so I thought, I wonder if there’s a way to make something that reinvigorates the format or at last lets people now that there’s more than just these aggregated films that are popular these days.

“it’s weird – you know you have those moments in your life when you know exactly where you were and what you were thinking? I remember thinking ‘This is a movie that no-one is ever going to make. I’m going to write a movie and it’s just going to be my way to get it out and it’s never going to get made.’ And it’s actually surreal that it did get made. Given what the process was to go from me in a coffee shop coming up with this idea that no-one’s ever going to make to actually executing something.”

I note that it’s often the films that directors tell me they wrote thinking they’d never get made that turn out to be the really good ones.

“Really?” asks Ryan. “I think that’s maybe in the nature of artists that we always start doubting every single thing we do. And I think there maybe is something to that adage that the harder something is, the more it’s worth doing. When things got really dark in the process of trying to finish this movie – because the thing that I was excited about was the format but I didn’t really take into account the logistical complications of making five movies simultaneously as opposed to one... You know when people say ‘Okay, you’re going to make your first movie: you’re going to come out with something contained, a few actors in one house, and you’re going to execute it really well’ – it was almost like I just swung the exact opposite way.” He laughs. “Let’s make five stories, let’s make each one of them have big set pieces, let’s make it sort of a period piece and let’s make it as difficult as possible. I don’t think I realised what I’d got myself into until I was past the point of no return.”

|

| It's the details that matter Photo: FrightFest |

I ask if he was going through the process under the constant threat of not having enough money to finish it, or if that side of things was better organised.

“It was kind of an interesting process,” he says. “I wrote the script that no-one would ever make and surprisingly there was a production company that liked it right away, so I though ‘Oh my god, I was wrong, this is going to be great!’ They were an awesome company and they were trying to get money and they basically found that nobody wanted to finance an anthology movie. And after about six months I was sitting in that same coffee shop and I was like ‘I think I just need to start making something at this point.’ I’d designed a movie that could be segmented out so I basically picked the most contained segment of the feature and we did a KickStarter campaign and we raised money and then we shot the first piece.”

He also worked on a documentary about the challenges of making such films, talking to directors like Joe Dante and Michael Dorrity and taking the opportunity to learn how they had overcome the problems he was facing, which also increased his passion for the project.

The short film that he made became the fourth short now included in the film, The Babysitter Murders, and was a big success, opening doors.

“So now we were in Hollywood and we were having all these top meetings,” he explains “And they really liked us and they said ‘What do you want to do? We’ll do anything.’ And we said ‘We really want to make this anthology movie,” and they said ‘We’ll do anything except that anthology movie!’ So it was kind of back to the drawing board again. And because we’d really extended ourselves to make that short as high on production values as possible, we decided to just start chipping away at the movie. I think the thought was ‘If we can’t find somebody to give us a bunch of money, we’ll just make them piece by piece over the course of, what, ten years? I’m not sure how long that would take.”

I have met people who have made films over that length of time, I tell him.

“This is not that different. I wrote this script in 2012, I shot the first short in 2015 and we finished in 2019. That’s a whole other story – if, emotionally, one person should be that doubled down on a project for so long. I’m not sure if it’s healthy. But...” he hesitates. “I don’t know if I could have done anything else. I was obsessed.”

|

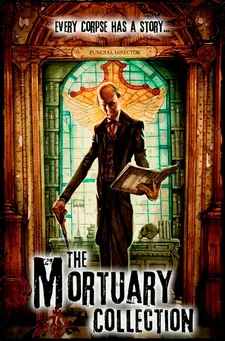

| The Mortuary Collection poster |

Eventually his meetings brought him into contact with Allison Friedman, who loved the script but knew her boss would never go for it, so suggested that she try to raise some money on the side. He agreed but then forgot about t because, after all, people say that kind of thing in Hollywood all the time. Then he got a surprise.

“Six months later I was talking to my producing partner Justin [Ross] and we were saying ‘Okay, let’s give up on the movie. it’s not going to happen. Let’s make other stuff and come back to it,’ and Allison called and she was, like, ‘I found some money. Do you want to make it?’

What came next, he says, was a process in which they had money and started work but kept being told that they would need more. Over the next year they assembled pieces of the film bit by bit to try and get the best production value possible.

“I’m not sure if that’s the most healthy way to make a movie,” he allows, “but it enable us to create all these really unique pieces. there were parts of the movie where we had a decent crew but there was a good part of the movie where it was just me and Justin and an actor.

“I kind of love those weird moments – even though they’re not, maybe, what you strive for as a filmmaker – those small moments when there were just a few of us felt the most pure and the most attuned to what I started doing this for. They actually kept me going.”

He talks about it as a period piece but, I suggest, each piece seems to have its own period – they fit together but they’re slightly different.

“I wanted it to be this sort of amorphous anytime time period,” he says. “I hated scary movies my whole life, right up until I was in high school, but the thing I loved when I was a kid – my one in to this world of horror – was The Twilight Zone. I think that original series created the foundation for a lot of my aesthetic. So when ever I think of timeless I kind of think of that 1940s, 1950s era where furniture wasn’t synthetic – everything was still wood, everything was old – a piece of furniture in your house could have been like a hundred years old...”

It’s a US perspective; I decline to mention that here in my house in Scotland, several pieces of furniture are.

“I think once you got into the fifties the different eras started to become very unique,” he continues. “And there’s something about the movie that I wanted to play like a fantasy, almost like a campfire tale, where it doesn’t really matter what the time period is. We know these are humans and we know they’re going through it and this allows us to have some separation from the stories, which then gives us the ability to do really wild stuff and experiment a bit more without losing people.”

Coming up: Ryan Spindell on just what that experimenting involved, spinning the tales, and working with Caitlin Custer and the legendary Clancy Brown.