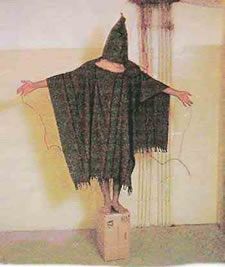

One of the iconic pictures from Abu Ghraib, branded Standard Operating Procedure by Brent Pack

Standard Operating Procedure is not the first documentary to be made focussing on the infamous pictures of smiling soldiers standing over degraded prisoners at Abu Ghraib - having its premiere at Tribeca Film Festival a little more than a year after Rory Kennedy tackled the subject in her equally hard-hitting expose The Ghosts Of Abu Ghraib. Although, inevitably, covering some of the same ground, both offer a unique viewpoint and as Errol Morris (Fog Of War, Thin Blue Line) pointed out during the post-premiere conversation with Jarhead author Anthony Swofford, this is a big issue. It's clear that he isn't done with it yet. Here's the edited highlights of what he told the audience about the film.

Anthony Swofford: I'm still pretty tense from the experience of seeing it. And experienced different emotions throughout, often some kind of sickness, a lot of sadness. I think the army CID guy really seemed the most, kind of, emotionally devastated by the process, the forensic process of investigating the photos and I'm wondering what your reaction to him was and how important for you his role in the film was?

Errol Morris: Since this is a film about photographs, he's absolutely an essential part of the film. I can't quite imagine it without him. In an interview, like you, I have no idea what's going to happen, you have really have no idea what you're going to hear and you can be surprised. That is certainly true of Brent Pack [the army investigator, who put together a timeline for the photographs]. Maybe the most surprising moment in the movie, he's speaking of the iconic photograph of the war, the photograph that has become the example of torture and abuse - the hooded man on the box, with wires - and he says that the picture depicts Standard Operating Procedure. I found it very surprising, dare I say ironic, and it is a very, very important moment in the film because - I can't speak for anyone watching the film, but I can speak for myself - it made me feel, we're in Bedlam, this is all crazy. Distinctions are being made that perhaps make sense to someone but don't really make sense to me, because the whole place seems like a kind of madhouse.

|

AS: She seems like she aged a decade, she seems herself like a victim of abuse, really. When she spoke about the role of women in the military [England refers to the battles women face at the hands of men] that was in the language of an abused person. As I was watching the film, I felt there was an agitated citizen behind the film. Someone who was bothered by Abu Ghraib and how that information was coming to us. And I thought that person was you. I’m wondering why did you decide to make this film. And why the soldiers on the ground – why their story? Why the story of these men and women, as you point out, all under the rank of staff sergeant?

EM: Well, of course, they were the ones who took the photographs. This is a big part of my motivation for making the movie – my curiosity about the photographs. One the one hand they are photographs that have been seen by many, many, many people – they are probably the most widely seen photographs in history – seen by hundreds of millions, and yet no one had ever talked to the people who took the photographs, no one had investigated the circumstances in which the photographs were taken. It is interesting that you have all these ideas about what the photographs show, without really knowing much about them at all. Midway through, I don’t think I realised this at the outset, I realised, hey, I’m making the flipside of the Fog Of War. I made one movie with a guy at the top of the chain of command, second in power only to Lyndon Johnson and now I’m making a movie about people who are really at the bottom.

AS: Near the end of the film Jamal Davis says: “If there weren’t cameras here, no one would have ever known about this, it wouldn’t be a story.” Let’s say there were no cameras there at all. How much of this do you think was possibly staged – like the human pyramid scene, for instance. Do you think any of them were really there just so that these soldiers could get this stuff on camera? Was there any sense that these soldiers wanted this as a trophy?

|

A prisoner named ‘Gus’ – Lynndie holding ‘Gus’ on a leash. The picture of ‘Gilligan’ standing on the box, with wires [in his hands]; this is an amazing part of the story, the wires were put on so they could take a picture – click! – the wires are taken off. The pyramid. All of these – how can I describe it? – tableaux vivant. I sometimes describe it as the Cindy Sherman from hell, all of these created so that someone could take a picture. All very, very, very interesting.

When I tried to ferret out why one [picture] was one and another was another [either a ‘criminal act’ or ‘standard operating procedure’]. Why ‘Gilligan’ with wires on the box was one and the leash was another, I never got clear answers.

Here’s my theory, for what it’s worth, call it my two cents-worth of opinion. In creating these pictures – the pyramid, ‘Gus’ on the leash – they were creating a picture of American foreign policy. I mean in the broadest sense.

I did this 17-hour interview with Janis Karpinski, believe it or not – two days. And as the interview progressed, Janis got angrier and angrier and angrier and angrier, and the last three hours of the interview are memorable. She started talking about how she identifies with Lynndie England – in itself a remarkable comparison because we’re talking to a woman who, at the time, was a brigadier general. They actually had met in October, briefly, by chance. A story that was described to me both by Janis Karpinski and Lynndie England. Janis said to me – I remember it very well, [although] it’s not in the movie, we’ll put it in the DVD extras, I promise – Janis said they had these representations of women in the military. There was the heroic woman, Jessica Lynch, and then they needed women as villains and she goes on to say: “It was Lynndie England and it was me”. A very, very strange and powerful moment.

I’ve often seen this war as a war of sexual humiliation. It’s no accident that American women were used to strip Iraqi males, to interrogate Iraqi males, to humiliate Iraqi males. To me, it’s no accident that Graner took his 90-some pound girlfriend [England], who was 5ft tall and 20 years old and created this picture [of her holding ‘Gus’ on a dog lead].

|

Another thing that you don’t know from the movie… Sabrina’s father was a cop, her brother was a cop, she wanted to become a cop, a forensic photographer. And she joined the military so she would have enough money to go to school. After taking the picture of the thumbs up, she went on to take over 20 detailed photographs of the body, which can only be described as forensic pictures; pictures basically providing evidence of a crime.

Here’s where the outraged citizen comes in. The CIA interrogator who I believe killed Al-Jamadi – we know his name. He has never been brought up on charges. Sabrina Harman spent a year in prison. I’m always a little baffled when people say, “They don’t express remorse”. They’re angry. The people who they know knew everything about this and have been involved with this have never been held accountable. And it goes all the way to the top. It’s wrong, deeply, deeply wrong. We looked at the photographs, we thought we knew everything there is to know about Abu Ghraib, we thought we understood everything that we needed to understand about Abu Ghraib. We understood little or nothing. Photographs reveal and they conceal. They serve as an expose and a cover up. We saw a glimpse of Abu Ghraib and it stopped us dead in our tracks because we thought we had someone to blame.

I have a theory that George Bush won re-election in 2004 because of the ‘bad apples’, because of the scandal. You would think, how could that possibly be the case? Didn’t he say that this was the worst day of his presidency? I don’t believe it was witting, I think it was unwitting, the chips fell into place, as it were. [They were saying] You want to know why the war is going south? You want to know why the entire Arab world is railing against us? You want to know why the insurgency is growing? You want to know why Iraq is in chaos? Blame them and the photographs – it’s there fault. They effectively become the scapegoats of the war. It explains to me, quite clearly, Janis Karpinski’s identification with Lynndie England. Blame them, so we don’t have to blame ourselves. I think it’s a very, very sad story. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think these ‘bad apples’ are lily white. I don’t think anything of the sort. I just think in the blame game they are way, way, way down low on the totem pole.

There are many things that are hinted at in the movie. How many people knew we had children at Abu Ghraib? That we kidnapped children, used them as hostages, as tools in order to force their parents to give information. No one really knows about this.

|

AS: Will you try to speak to Graner, when he gets out of prison?

EM: The thought has crossed my mind.

If been asked, quite often, whether it is easy to get these interviews. The answer is, of course not. It’s incredibly difficult, every single one of them. Not always for the same reason but there were always reasons why people were reluctant to talk, had no interest in talking, were fearful about talking.

AS: Was anyone grateful for the chance to tell their side of the story? At what point did they turn from being reluctant to realising you were offering a remarkable chance to tell their story.

EM: Of course, I shouldn’t speak for them but I do believe that everyone was grateful for the opportunity to tell their story and I, in turn, am grateful to them. It’s not a movie that can provide answers to every question that you might have or I might have – far from it. It’s a movie that, for me, raises questions and urges you to think about things that you might not have thought about before and if I’ve done that, then the movie has served it’s purpose.

If anyone still believes that somehow the Pentagon were unaware of what was going on, there is just overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

When I was making this movie, I would get hundreds of questions along the lines of: “Have you found the smoking gun.”, “OK, do you know where the smoking gun can be found?”, “Where is the smoking gun?” What is so odd about this story is that there are smoking guns everywhere. I don’t know whether we’re willing even to see a smoking gun if there’s one right in front of our faces. Correct me if I’m wrong, but the president of the United States just announced he was involved in all of these meetings and approved all of these policies. You can’t see a smoking gun if you’re unwilling to see it.

Can I ask one question? I was fearful that this would be seen as an anti-military film. I feel the military has been very poorly served by this administration. Under-equipped, untrained, even worse, not enough people in any given role to do the job they’ve been asked to. Then somehow when it all collapses into chaos - is this a judgment on our military or is it a judgment on the way our military has been put to use by its civilian commanders?

AS: I think it’s the latter. I think a military person would watch the film and understand that you’re trying to understand the position they’ve been put in. It doesn’t feel anti-military to me.

EM: I’m glad.

The audience were then invited to ask questions, here’s the highlights.

Q: I’d like to know if you were given the opportunity to interview any of the Iraqi men who were held at Abu Ghraib and whether you considered including that in the movie?

EM: I tried to interview the Iraqi men who were in the iconic photos, because I felt the story should stay with the photographs and the people who were associated with them. I tried really, really hard to find ‘Gus’ and ‘Gilligan’, for example. I paid people on the ground in Baghdad to try to help us find them. The military was of no help, whatsoever. We don’t know if they’re alive or dead or if they’re still in a prison somewhere. We found out nothing. A man came forward and claimed he was the man under the hood in the iconic photographs. He wasn’t, he was an imposter but he had been at Abu Ghraib during that same period of time, on that same tier and I interviewed him. And when I asked him about Sabrina Harman, he told me: “You know, I really liked Sabrina, she was a good one.”

Q: When you conduct an interview, how much of a pre-planned outline do you follow or do you allow the conversation to unfold in a way that’s a surprise to you?

EM: I never have a list of questions. I never know where the interview is going to go. I have no idea, really, what someone is going to say to me. I expect to be surprised.