|

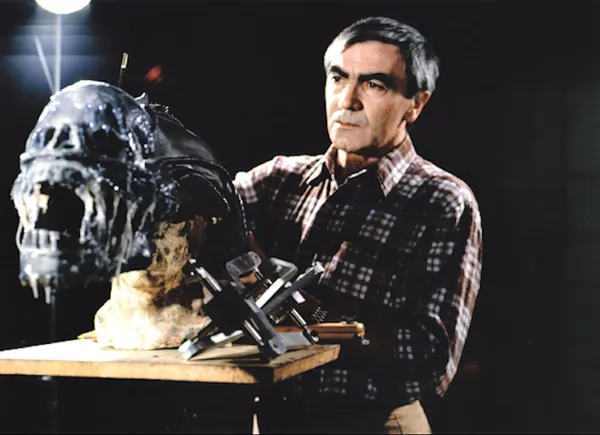

| Carlo Rambaldi’s double mouth model for Ridley Scott’s Alien, starring Sigourney Weaver, Harry Dean Stanton and John Hurt Photo: courtesy of Fondazione Carlo Rambaldi |

When I met with Vittorio Rambaldi, son of three-time Academy Award Visual Special Effects winner Carlo Rambaldi, we discussed the grand legacy of his father. We spoke about the solar system he created for Luchino Visconti’s Ludwig (starring Helmut Berger, Romy Schneider, Helmut Griem), the special effects for Joseph Losey’s Modesty Blaise (screenplay by Evan Jones and Harold Pinter, starring Monica Vitti and Dirk Bogarde), and the little aliens for Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (François Truffaut, Richard Dreyfuss, Teri Garr, Melinda Dillon, Bob Balaban).

|

| Vittorio Rambaldi with Anne-Katrin Titze on David Lynch: “He had these very strange ideas about Dune.” |

We went on to Carlo’s love of Pinocchio, the fact that he immediately bonded with David Lynch, for whom he created the Sandworms in Dune (starring Kyle MacLachlan and Virginia Madsen), an anecdote about the double mouth for Ridley Scott’s Alien (Sigourney Weaver, Harry Dean Stanton, John Hurt), and how a midnight phone call from Spielberg would lead to Rambaldi’s most iconic creation.

MoMA and Cinecittà Present: Carlo Rambaldi, a 15-film retrospective, includes his Oscar wins, for John Guillermin’s King Kong (starring Jessica Lange and Jeff Bridges); Alien; E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, plus Dario Argento’s Profondo Rosso (Deep Red, starring David Hemmings); Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (Jane Fonda, Marcel Marceau, David Hemmings, Ugo Tognazzi); Pier Paolo Pasolini’s I racconti di Canterbury (The Canterbury Tales); Dune, and Close Encounters Of The Third Kind.

We started out with the first awareness of dad as a “monster builder” in the Italian film industry in the 1950s and Vittorio let me in on the unknown fact, that it wasn’t Siegfried’s dragon, but mechanical sturgeons for a documentary about the Po river that began Carlo Rambaldi’s unequaled movie career.

From Rome, Vittorio Rambaldi joined me on Zoom, the day before the opening of MoMA and Cinecittà Present: Carlo Rambaldi, for an in-depth conversation on the legacy of his father.

Anne-Katrin Titze: MoMA and Cinecittà are having a big retrospective of your father's work. Are you proud?

Vittorio Rambaldi: Very much so, very much so. His career has been just a shooting star. I mean, it's exciting, and as a family, of course, we are incredibly grateful to the United States, to Hollywood, for the gigantic opportunity that was given to my father in his own career.

AKT: Do you remember the first time that you, as a child, became aware of your father's films?

VR: Yes, probably when I was in elementary school. Because in those days, in Italy, when you were a student at elementary school, the teacher, at a certain point during the year, would ask all the pupils: What does your father do for a living? That question threw me off, because I didn't know what to say.

AKT: A magician?

VR: Well, exactly, I mean, so I came up with an idea that I said, my father builds monsters. At that point, the teacher called my mother through the school.

|

| Carlo Rambaldi in his visual effects lab Photo: courtesy of Fondazione Carlo Rambaldi |

AKT: Thinking your father was Victor Frankenstein!

VR: Requesting an urgent meeting! What does your son mean? My mother explained that my father worked as a movie special effect specialist in the Italian movie industry. Even though, in those days, the term special effects designer was not in vogue at all. People in the Italian industry that were actually doing what we know now as special effects were simply called Tricksters.

AKT: Hmm, interesting.

VR: And the effects were called tricks. Photographic tricks, manual tricks, that type of thing. They didn't have much of a recognition in those days.

AKT: Trickster is a good name, though, because Trickster also, in myths, includes the idea of someone who influences the life of others, who is a kind of catalyst character.

VR: Exactly! The etymology was quite right about that, yeah. It was really an industry in its infancy. We're talking about the early and mid-1950s.

AKT: I noticed that Carlo Rambaldi’s first credit on IMDb is Dragon Maker for a Siegfried film [Sidfrido, 1958]. That fits very well with your memory.

VR: That's right, that's right.

AKT: First came a dragon.

VR: That was actually his first “official” effect, but when he was quite young, he made another one for a documentary in the northern part of Italy. Do you know the Po River, the big river that really cuts across the northern side of Italy?

AKT: Sure.

VR: And in those days, in that area, when the river actually flowed into the ocean, the Adriatic Ocean, there were sturgeons. You know sturgeon, the big fish? There was a guy, a documentarian, that was shooting a documentary about the fishermen who would fish sturgeons. But in those days, for some reason, sturgeons were not there to be seen. Imagine! So he called my father.

|

| Carlo Rambaldi aliens for Close Encounters Of The Third Kind: "Spielberg wanted that sort of hand signal that signifies a sort of message to the Earthlings.” |

My father was really beginning his career. He said, Carlo, I have a problem here, because I'm shooting this documentary, but the fish are not there, the sturgeons are not visible. Carlo said, don't worry, I'll go into my lab, I'll build you a mechanical sturgeon, the real size, so you can use that in your documentary. And obviously, the filmmaker said, how is that possible? Anyway, he built these little sturgeons, big sturgeons, and the filmmaker was able to complete his documentary. Not too many people know about this.

AKT: It's great. What a great story. I mean, all of these very, very different creatures and fantastical elements he made! For Visconti's Ludwig, did he make the Milky Way, the projection on the ceiling?

VR: Yes, he made the whole apparatus with moving moons, rotating moons, the sky flying over and moving and coming back with the stars, the whole mechanical contraption that is in the movie, right?

AKT: Perfect, that's so beautiful. It's one of those unforgettable moments in a very long and gorgeous film. Did he do any other visuals for Visconti? Nothing in the grotto with the swans?

VR: No, just that. Visconti, of course, being a very strict, incredibly strict and very serious director, really wanted this incredible contraption, and there were some difficulties with the lights. Too close to the ceiling that could be burning that acetate film that made up the universe. But everything went well.

AKT: We're starting here maybe with the more obscure or oddball films, and then we get to the big ones. I had never, before seeing the program at MoMA, heard of Modesty Blaise, directed by Joseph Losey, screenplay by Harold Pinter, starring Monica Vitti and Dirk Bogarde. I watched the beginning of it. I didn't get very far. It's a very strange film. Can you tell me a little bit about it?

VR: As far as Modesty Blaise, I have to go back to my notes, because there's so many films that he made. He made a full mechanical body of the actress with something on her back. And some sort of a balloon that was actually kept to earth. So he made a few effects here and there, very particular effects, not too many for that movie in1965. So just the mechanical body of the actress.

|

| Steven Spielberg to Carlo Rambaldi on E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial: ”He has to be innocent. He has to be a mix of an old man and also a child.” |

AKT: I'm glad that they're showing it at MoMA, because it is something so unknown.

VR: It's a rare film, Joseph Losey, of course, known for his experimental work, British director.

AKT: Close Encounters of the Third Kind, I love this film. I love it because of Truffaut's role, I love it because of all the odd things that are happening in there. Your father made the aliens. The first, the long, spindly one, almost looks like a Giacometti!

VR: The first one that comes out, it makes that sign with a hand. Remember that sign?

AKT: Yes. Your father studied painting and sculpture beforehand, so there were influences.

VR: Right. The effects were just that, the little creature, the small alien, not the big… I mean, there are two aliens. I think the first alien is the one that comes out of the spaceship, and he has very long forearms, and is very, very sort of skinny and that was just for that little moment there. But then, we have the smaller one that looks like a child. It has the same sort of body feature of a child, and for that, he made not only the beautiful face, but also the mechanical arm. The mechanical arm that does the five movements that are really duplicated in the sound. Remember the five notes that the spaceship makes?

AKT: I do.

VR: So Spielberg wanted that sort of hand signal that signifies a sort of message to the Earthlings. And that is the only effect, and obviously it appears at the end of the film. No other effects were done, but, something that obviously still can be remembered, because it was such a sweet moment in a beautiful film. Such a sweet moment towards the end of the picture.

AKT: And that convinced Spielberg to say, okay, he's the one to make E.T.?

VR: Right. Well, what happened was that Spielberg saw King Kong, the first big film, and also the first Academy Award [for Carlo Rambaldi] was King Kong, the one with Jessica Lange. So he had seen that film, and he was quite impressed by it. And therefore, when the time came for E.T., he had asked, before calling my father, he had asked some of the best technicians in Hollywood to build that kind of an alien. But he was not satisfied with that, and he went on shooting Indiana Jones, the first chapter of the franchise.

And when he came back, he was nine months behind schedule with E.T.. So, once again, he did not like what he saw, and he called my father. I remember the phone call, it was at 12 midnight. And he called up. My mom answered the phone, and obviously, when you receive a call at 12 midnight, you think something bad has happened. And Spielberg goes, "I'm sorry to disturb you, but I have a big problem."

AKT: Not bad for him, bad for Spielberg in this case.

VR: Exactly. And Carlo called me up, because his English was so-so. So, Spielberg said, "Carlo, I have a big problem here. I'm behind schedule on my film, and I need to meet you immediately, because I need you to build an extraterrestrial." My father was totally shocked by this, and so said, "Okay, let's meet tomorrow." I went there too, of course, and we met. Spielberg explained what he had in mind, this strange alien that was so different from all the films with aliens.

Usually in the sci-fi tradition of Hollywood films, the aliens are always kind of bad creatures. They always are lizard-like, and they just want to kill everybody. Spielberg did something quite new. For the first time, now we see a friendly alien who is afraid of being on Earth. And so he started to describe the physical characteristics and also the personality, and so on and so forth, so we understood completely, somewhat.

And he said, "Carlo, I want this alien to be absolutely innocent. He has to be innocent. He has to be a mix of an old man and also a child." When my father and I came home, we would start talking about it in the car. I said, "This is quite a difficult task. How can someone be old and young at the same time?"

AKT: And innocent! Innocent doesn't mean neutral.

VR: That's right. Innocent is such a big concept, right? So we start thinking about this, and obviously, a few weeks went by. And my father said to Spielberg, "How much time do I have? Because I was thinking about this. Before we get any further, I would need nine months to do this."

VR: And Spielberg said, "No, Carlo, you've got six."

AKT: Okay, a quick baby! Not nine months.

VR: Yeah, exactly, the timeline of making a human baby. Yeah. So, okay, the biggest problem was, of course, where do we find innocence? How can we materialise innocence? Maybe you read it somewhere, but at that time, we had a cat in the house. It was a female Himalayan cat. Himalayans are like Angora cats, with long hair, very white, with a beautiful triangular shape face with blue, intense blue eyes.

|

| A Carlo Rambaldi sandworm from David Lynch's Dune |

And one afternoon, he was sketching the alien. And he turns around and sees the cat. And he is flabbergasted, a revelation or something. That's innocence! The face of a cat. The face of a cat is the innocence I'm looking for. So what he did, he took the face of a cat, which is obviously triangular-shaped, he lifts up the nose. He made the eyes a little bigger. Obviously, the ears went and then he redesigned the face, and that's exactly what the innocence was.

And therefore he placed the face on the body, and then presented a preliminary sketch of this creature, and Spielberg went through the roof. He said, that's exactly what I was looking for. That's exactly what I was looking for! So he gave us the green light, and the methodology was that you go from the sketches into a 3D clay model. Therefore, we went through that 3D clay model, Spielberg came back once again to our lab, and he looked at it, and had a few modifications; he wanted the behind like that of Donald Duck. The head, very pronounced towards the front.

And all the wrinkles. That's the other idea that my father had. Besides the innocence. And the fact that he had to be like the body of a child in order to give the idea of the age, wrinkles were the only possibility. So that when E.T. moves his face and makes expressions, that face wrinkles up a little bit. And that coupled with the imprint of innocence, was that combination that people wanted.

AKT: And it's so perfect, because there's this alien that represents the beginning of human life and the end of human life, plus your cat is immortalised. Who can hope for anything better than to have your beloved cat there as an icon of cinema? And again, here is the animal, following the sturgeon that you were talking about in the beginning. Now there's the cat and the duck’s behind. Did animals play a big role in his work in general?

VR: That's right, because in Italy in the Fifties, we had a film genre called the Peplum films. I don't know if you're familiar with that. The Peplum films were sort of like the combination of ancient mythology, Greek mythology, coupled with superheroes like Hercules. And those big bodybuilders, American bodybuilders came to Rome to film all these ideas. I mean, the scripts borrowed a lot from the ancient myths, like the Cyclops, and Medusa, and all the strange creatures populating Greek drama.

He had a lot of training in doing those things, like the meat-eating flowers, the Cyclops, all kinds of mythical creatures, like Medusa with tentacles. So, for many, many years, about ten years, the Italian film industry was populated by these films. And the only one who was able to build these monsters was my father. Dragons, incredible fish monsters, he did so many films, so he had a lot of experience translating animals and translating myths into a visual sense. I mean, myths have sparked giant bats, winged creatures, and so on.

AKT: Did your father ever tell you myths or fairy tales as a child? I saw that you also are a writer of children's books.

|

| MoMA and Cinecittà Present: Carlo Rambaldi poster in New York Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

VR: Right, yes. I mean, one of the Italian fairy tales that he really loved a lot was Pinocchio.

AKT: Obviously!

VR: Obviously, right? You have a puppet maker there. Pinocchio was really his love, his passion. And, he always told me, but he never actually sat down with me, didn't have the time, to do anything that a normal father would do, you know, telling stories to his own child. No, he never had the time to do that. But I remember his passion because he used to collect old Pinocchio books, old editions coming from Italy. A lot of space in his lab was dedicated to collecting all these old editions of the book, of the original book. So, he loved that.

AKT: It fits beautifully with his life’s work. Let’s talk about David Lynch's Dune!

VR: Yeah, David Lynch was another very interesting guy, first of all, to deal with, because he was also a painter. And I remember him coming to our studio and meeting with him.

AKT: Also both were making furniture, objects. The two of them were both hands-on.

VR: Exactly. They connected immediately. They connected immediately, even without being able to communicate directly. My father only spoke a little English, not that much. But between artists, you know, the rules and conventions are the same in both languages. So David was really an interesting person to talk to, and he had these very strange ideas about Dune. And of course, my father would not interfere in anything. You need this, you need a strange creature called the Navigator.

Of course, I'll give you the Navigator. So the Navigator was one big one of those worms, the sandworms. We did those, the Navigator, the sandworms. What else did we do with Dune? Let's see, let me check my list. I got so many things. No, I think the sandworms were quite a few, because we had two giant ones. The big ones that actually come up out of the surface and eat the spaceship, and then we had smaller ones for long shots. The Space Guild Navigator, that's the proper name for that. The Navigator and the Arrakis warps. That were the two elements.

AKT: There's also the worm-like creature in Alien, of course, the other big film he is known for.

VR: Yeah, Alien, the first Alien, the 1979 Ridley Scott film. He was not responsible for the actual look of the Alien. That belongs to H.R. Geiger, the Swiss artist. But he was called in by Ridley to do the double mouth, the double mouth effect. And I remember on the set, I have a little bit of an anecdote here, at the Shepperton Studios in London, all the departments had its own bungalow, its own lab. And Ridley Scott came over one day to check on the creature, on the double mouth movement.

And he had a cup of coffee in his hand. So he wanted to try the test, the double mouth thing, and he sat there, and he had this cup of coffee in his hand, a paper cup. And that thing was put in motion, and the double mouth shot out at such a speed that it hit the paper cup and shredded it to pieces, right? And Ridley jumped… jumped backwards and said, oh my god, that's a tad too fast! So you had to recalibrate that movement. That is the contribution to the film.

AKT: I mean, the contributions that your father made to cinema are incredible, looking at the list of films he was a part of. And if you think about the pioneers of cinema - Georges Méliès started out as a magician and a toy maker! So the beginning of cinema is deeply rooted in special effects. This is how cinema began.

|

| Carlo Rambaldi’s work for Luchino Visconti’s Ludwig: “He made the whole apparatus with moving moons …” |

VR: Exactly, but one of the most important elements is that by and large, for many, many years, the 50s, the 60s, the 70s, even all the effects that he made, even through the 80s and 90s, it was a totally experimental science. Each film was a different problem to solve, and you had to come up with something new, always newer compared to what he did in the previous film. So, it was a science in constant development. And therefore, every movie that he made, every character that he made, is one step on the ladder of perfection. That's why when you look at E.T., E.T. is the compendium of all the techniques, all the experiments that you had done in the past, in terms of materials, in terms of mechanisms, experiences in that.

I remember when I was a kid, being present in his lab with his crew at the moment. And sometimes he’d run into a problem, like, this particular latex, or this particular rubber is not working. We got to find something else, but there's not something else on the market. We need to fabricate it ourselves, by combining chemistry and mechanics and electronics. I mean, it was a challenge.

AKT: Also of engineering, inventing everything.

VR: Right, you could not go buy a book about, how do we make the mechanism to move the mouth? Oh, okay, right here. That's on page 53. Page 53, you have the mechanism. No, everything was done in the moment. Once the mechanisms was built and worked, obviously, it was used for the next movie project. But up to that moment, many, many sleepless, sleepless nights, I can guarantee you.

AKT: To solve problems like that, he really needed to be somewhat of a magician. It's fascinating, and thank you so much for telling me these stories!

VR: My pleasure!

AKT: I'm sure people will very much enjoy this series at MoMA.

VR: Thank you so much.

MoMA and Cinecittà Present: Carlo Rambaldi runs through Wednesday, December 24 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Another reason to visit MoMA is the Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination exhibition, which opened on Sunday, December 14 and runs through Friday, July 25, 2026.