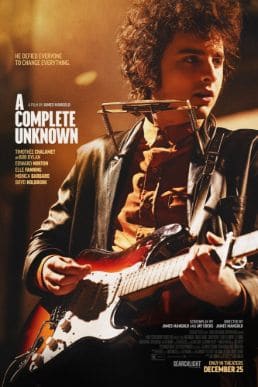

Eye For Film >> Movies >> A Complete Unknown (2024) Film Review

A Complete Unknown

Reviewed by: Andrew Robertson

It's 1961 and a young man is on his way to meet Woody Guthrie. We've heard him sing from a record, scratch and all, seen his contemporary Pete Seeger on the courthouse steps for contempt of Congress caused by Communism. We get a first few steps on an oft revisited stretch of New York pavement, not Highway 61 but the West Village. A cradle to generations of cultural talent, it's literally akilter to the rest of the city, its streets 'off the grid' and differently aligned.

There's a sense of trying to build continuity, something (again literally) handed from legends of folk to our protagonist. That's the variously named Bob Dylan, a subject that unlike the harmonica is never quite grasped. To borrow from one of the scores of his songs that are briefly on the soundtrack "Look out kid, don't matter what you did." As in Subterranean Homesick Blues where "the pump don't work cause the vandals took the handle," A Complete Unknown doesn't work because it never gets a grip on its subject.

That's not a new problem for the variously named Lucky and Boo. When Todd Haynes tried it he wasn't there. Joining a short list of biopics of winners of the Nobel prize for literature, part of a much longer list of films about winners who've tended to be recipients for the alphabetically adjacent Peace and Physics. The film ends with a mention of Dylan's win, but that's more than 50 years after its opening.

Based, at least in part, on musician/historian Elijah Wald's book Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the Sixties the film covers a span of about five years as Dylan becomes the figure whose Highway 61 Revisited defined a generation for a particular generation. That's a very particular construction, and I think a big part of the film's problems.

Director James Mangold has directed a few Westerns, including the remake of 3:10 To Yuma and Logan which owes enough of a debt to Shane that I'm counting it. A slick youngster coming to town is a classic trope, whether the saloon doors are flapping in Tombstone or West Tenth Street. He co-writes with Jay Cocks, who is previously most associated with Scorsese's work. No stranger to co-writing, nor the streets or Gangs Of New York with any collaborative effort it's impossible to say who's held sway. What is clear is the extent to which we're often shown that something is meaningful by reaction shots.

Often doesn't begin to cover it. Once I'd caught it as a construction I found myself counting. I think there are 11 during The Times They Are A Changing. As a central element of the transition from folk to rock'n'roll, the demographic pivot of the Baby Boom, it's self-reflexive. It may perhaps not be obviously so, but to spend as long looking at folk looking at something starts to move from the fun-house mirrors to the clownish.

It's one of several sideshows in a story which at times feels almost parodic. There's a composite shot of Dylan at the March on Washington for Jobs that feels clumsier than its equivalents in Forrest Gump or Zelig. There are appearances from Johnny Cash (Boyd Holbrook) but that's a line Mangold has walked before. A montage of their correspondence and its consequences with jet-liners and latterly car parking feels forced. A reference to the Beatles manages to turn contemporary disdain into a reference to the shared continuity of the Travelling Wilburys.

The shortest of those was Dylan, and while Timothée Chalamet often manages to be somewhat fey he's best with the cape and cowl of sunglasses and that bouffant pompadour. The infamously mercurial Dylan is a hard act to follow, let alone capture, and while Chalamet has been compelling as a youth leader he's also been somewhat flat. Though he's calling to young people and singing his own songs I found him more charming in Wonka than here.

Some of that's the character though. Bob is a difficult cat, and his mettle does not go unalloyed. Monica Barbaro's Joan Baez and Elle Fanning's Sylvie Russo are his most prominent romantic and creative entanglements. Edward Norton's Pete Seeger and Scoot McNairy's Woody Guthrie are steward and stewarded of folk's legacy. The politics of portrayal aside it's usually left to Norton to convey the leftist hopes of genre which are very easily caricatured as the purist desires of the festival committee. His earnest explanation of the teaspoon brigade never quite sets out what they're trying to balance. That recurrence of reaction hits a pinnacle with yet another reaction shot, with a stacked set of Cash, Baez, Jesse Moffette (Big Bill Morganfield) and Bobbie Neuwirth (Will Harrison) all looking on from off-stage.

There are not the only reactions. Toshi Seeger (Eriko Hatsune) has to disarm a situation and the committee's commitments start to shade percussive rather then persuasive. At the same time, and heretically, it's just music.

There's lots of it. At least 50, rarely delivered in full though those that are often have those reaction shots to ensure reception. In and among the credits you'll see Chalamet and Norton and Barbaro credited for instrumentation and vocals, and one of the films real strengths is that these are real performances. That's part of its difficulty too, it's a move towards authenticity that throws weird light across the whole endeavour.

We're based in a true story, one where there is and was a crisis of commercialism, an attempt to preserve a pastoral past and the (invented) traditions of American folk, the genuine struggles of the civil rights movement, the birth (or at least rebirth) of rock and roll, integration in radio and recording if not anywhere else. The Cuban Missile Crisis and the assassination of JFK are waypoints for the wayfaring stranger in particular in a love triangle that at times feels pointless. To profess to the authentic and the real and the genuine is undercut by product placement for Budweiser and Levi's. The notion of historical documentation is undone by moving the shout of "Judas," forward by 296 days and west by about 3200 miles. That the occasion is referred to as the Royal Albert Hall concert through misattribution when it was Manchester's Free Trade Hall just further muddies the waters. The eagle-eyed or -eared might spot the song Keeping Secrets Will Destroy you by Bonnie 'Prince' Billy, though Will Oldham wouldn't be born until five years after the film's ending. He wouldn't release the album with which it shares a name and upon which it is not found until 2023.

That battle for authenticity and its perspective is one of the things that leaves the subject of A Complete Unknown no less understood at the end. A moment or two of Now, Voyager and its reflections does give us some sense of the plasticity of the ingenue born Robert Allen Zimmerman who'd grow up to be Tedham Porterhouse and Blind Boy Grunt and Elston Gunnn among others. Chalamet's efforts to capture Bob's performances as a performer and a person are not in vain, though vain he often was. There's sometimes a bit of a lag between the cocksure and the corn-fed, the small town boy and the man of the Village. Where it rings false there are times when that feels apt, New York has plenty of self-made men who've outstripped those to whom they were apprenticed. What it also has is plenty of other stories.

In cinemas overlapping with a slew of other biopics of musicians, from the operatically sublime to the popularly simian, A Complete Unknown relies more on its subject than its own quality. Opening and closing with the hiss of a needle on a record it purports to an authenticity that is itself imagined, a glossy act of nostalgia that feels antithetical to the shock of the new that Dylan's apparently meant to represent.

At almost two and a half hours, its heft could be regarded as an act of demand or belligerence on a par with much of Dylan's own spikiness, but the tropes and rote repetitions to smooth it into a comforting shape limit its appeal. In the end it lacks the inventiveness, the difficulty, the novelty that characterised Dylan's output. While Chalamet does manage at times to make it clear why people would work to get past what made him hard work that work doesn't always work. That struggle to represent the struggle for authenticity has produced something with a mass-market sensibility, something pasteurised to get past your eyes. The most symbolic element is the recurring presence of a bottle of peppermint schnapps that suggests the strong and the sweet, the economics of music and addiction, the rough made smooth, but also, and most importantly, something cheap and cloying.

Reviewed on: 16 Jan 2025