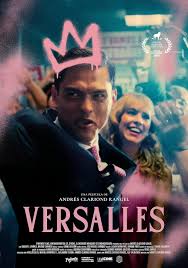

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Versalles (2025) Film Review

Versalles

Reviewed by: Edin Custo

If the title isn’t a dead giveaway, Versalles tips its hand early. A cardboard cut-out of Chema (Cuauhtli Jiménez), a self-made Mexican state governor, greets us with a stiff little wave: not to the crowd, but with the back of his hand, like a royal. The image foreshadows both his illusions and his fate. He may be on his way to the presidency, but the posture already belongs to a king.

The fall is swift. Chema discovers his party has picked a different candidate as presidential frontrunner; the slight is racial and class-based as much as political. When he tries to protest, a party boss shuts him down by reminding him of a private scandal caught on camera and orders him back to his country estate. Once he’s removed from the capital, Versalles becomes a study of the five stages of grief that, halfway through, mutate into stages of madness.

At the hacienda, Chema is surrounded by workers who look like the people he claims to represent. Instead of solidarity, what emerges is feudal. His Spanish wife Carmina (Maggie Civantos), light-skinned and obsessed with European art, is eager to collaborate in the fantasy. The staff become his court, the house his palace, Independence Day an excuse to wave the wrong flag: the imperial banner from Maximilian’s short-lived European-backed monarchy. Clariond is less interested in political intrigue than in what happens when a wounded ego with power is left alone with his own myth.

Jiménez is very good at charting Chema’s slide. Early on he still feels “of the people”, close to the workers. Once the betrayal lands, he’s consumed by a single inner line: “This is not fair. I should be there.” Grievance slowly licenses everything that follows.

Civantos plays Carmina as both accomplice and director of the fantasy. She doesn’t interrogate colonialism; she simply inhabits its gaze, arranging locals like baroque or rococo subjects and manufacturing poverty and “authenticity” when reality isn’t picturesque enough. Clariond is careful not to make her the sole villain: Carmina and Chema clearly function as two faces of the same monster.

Composer Carlo Ayhllón gives the whole thing an ornate sheen. His original score is woven together with recognisable slivers of European classical pieces, Vivaldi, Bach, Tchaikovsky, Handel. The soundtrack itself becomes part of the couple’s ersatz Versailles. There is real dark comedy here too: workers fanning out through tall grass to look for Chema’s severed finger after a botched attempt at manual labor; the powdered faces; the cardboard sovereign presiding over it all. Yet the incongruousness of a contemporary Mexican countryside dressed up as historical Versailles sometimes shows, and it’s not always clear whether that dissonance is deliberate or a result of limitations in the production design and costumes.

Grounded as it is in very specific Mexican histories and wounds, Versalles now plays as oddly prophetic, shot two years before a very real North American leader began turning his own White Hacienda into a kind of Versailles.

Unlike the royalty of the real Versailles, no heads roll in Chema’s little court (only a single finger). The workers grumble and suffer, and the palace coup is feeble at best. As a whole, Versalles never quite coheres into the devastating character study it is reaching for. Perhaps that is fitting in a world where the same kind of half-sketched strongmen keep getting elected anyway. It ultimately lingers as a cluster of images: the cardboard king, the whitened faces, the imperial flag on Independence Day; and as a bleak joke about how far a wounded man will go when denied the crown he feels he deserves, and how little the system has to change to absorb him back in.

Reviewed on: 21 Nov 2025