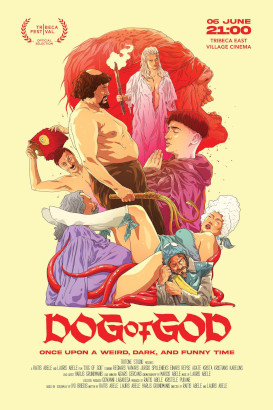

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Dog Of God (2025) Film Review

Dog Of God

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

They may not come across that way onscreen very often, but werewolves are complicated figures – one of the last widely recognised version of the shapeshifter characters which appeared in pre-Christian beliefs all across Europe. Older tales often present wolves as renowned for their intelligence and caution, an appropriate reflection of their natural behaviour, and it’s only gradually, under the influence of both Christianity and the economic pressures stemming from the switch from hunting to herding or single-site animal husbandry, that they became popular folkloric villains.

Some places held onto the old ideas longer than others. Livonians still tell tales about heroic werewolves who fend off their brutal kin, and the Livonian vīlkatõks remains morally ambiguous. Dog Of God, a boldly animated tale which won acclaim from attendees at Fantasia and Frightfest alike, features such a character, an apparently religious man who describes himself as wandering the Earth and always finding himself exactly where he is needed. Going by the name of Theiss (Einars Repse), he is introduced in the thundering prologue as a man out to castrate the Devil (another favourite motif in the folklore of the region), and although he disappears for some time afterwards, his presence colours everything else that we see.

Some might feel that a little colour is sorely needed. 17th Century Livonia, as presented here, looks pretty grey. It’s drizzling when we arrive, up in the fields on the hill. A cow takes a shit and a man steps into it deliberately, as if to warm his bare feet. Crows call overhead and a low, sonorous bell summons the villagers to file into the church. The ceremony that follows is not very inspiring. Some of the people will later admit that they go for the free drink. Screwed over by a succession of rulers for several centuries, these are not people who put much stock in promises. Their focus is on earthier things. Indeed, even the priest, Buckholz (Reginar Vaivars), makes a poor job of hiding his lust for local bartender Neze (Agate Krista).

Sent to spy on Neze, the priest’s orphan minion (Jurgis Spulenieks) – who is referred to simply as Klebis (‘cripple’) although he finds it insulting – discovers her giving milk to serpents and toads in the practice of ritual magic, whereupon she is charged with witchcraft. The baron (Kristians Karelins) who presides over the area is hesitant to let the people kill her, however, seeing her as potentially helpful in his quest to overcome the physical difficulties he is having and successfully impregnate his wife. His concern is primarily with his need for an heir, but the presence of the Devil’s testicles is going to have a powerful effect on the carnal appetites of practically everybody in the village, giving rise to scenes which, though rotoscoped, recall the work of Ken Russell or Tom Tykwer.

Meanwhile, the disappearance of the village’s sacred relic, a piece of holy straw, sends the priest into a panic, and implies that it may have lost its protection against the incursion of sin. Alternatively, this might be seen as heralding the collapse of an order which the downtrodden villagers will be better off without.

Sin, heresy and sexual ecstasy intertwine in a story which lacks theological depth but probably approximates fairly well the understanding of most peasants and low status clergy at the time. The folkloric elements are handled well, and the film is successful in capturing the psychology of a people living close to the land, intimately connected to the natural world. Even the nobles exhibit this, with a marvellous scene in which the baron feeds his wife an assortment of obscure aphrodisiacs. It is only the clergy, self-consciously removed and dismissive, who become vulnerable to nature’s own cruelties, resulting in a section of the film where we cannot be sure if what we see is intended to be interpreted as real or as a distortion stemming from the consumption of fly agaric.

The choice of rotoscoping here would seem, first and foremost, to be about enabling the interaction of the human and fantastical elements of the film without either blowing the bank or compromising the subtleties of dramatic expression. The overall quality varies – in places it looks crude and, frankly, unfinished – but praise is due for the levels of detail to be found elsewhere, and for the way that the artwork uses light. There’s a wonderfully realised scene in which a man is washing his face and we see him from underneath the water. When people are observed throgh windows, we get a sense of the thickness of glass and all the tiny stains and scuff marks made by insects of cobwebs over time.

All this detail, and the film’s sometimes humdrum, sometimes absurd events, are given further context by a huge electronic score. There are places where this seems intentionally designed to be unpleasant, out of balance, such as that encounter with the Devil, when it’s proper that viewers should feel ill at ease. Elsewhere it ebbs, or surges forward with a different tone, encouraging us to get caught up in what we see.

The film has been criticised for the slightness of its narrative, and this is fair, though it packs a punch when its various strands finally come together. It has to be said, though, that many films which are similarly slight don’t face the same level of disdain – the problem would seem to be that being unusual and compelling in some regards creates a seeming obligation for the film to deliver on all fronts. It doesn’t, and it is far from perfect, but it retains audience appeal and remains an interesting experiment – one which will leave you wondering what the brothers behind it are going to do next.

Reviewed on: 23 Aug 2025