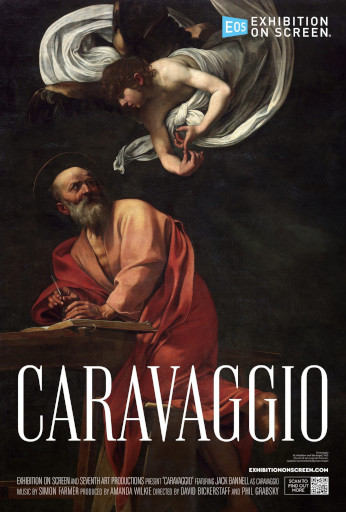

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Caravaggio (2025) Film Review

Caravaggio

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Part of the idea behind the Exhibition on Screen series is to attract the attention of people who don’t normally give much thought to pictoral art, and with this in mind, the team behind it have found a variety of ways to add dramatic framing to their subjects. Fans will have watched Van Gogh battle for his sanity, admired the proto-feminism of Mary Cassatt, indulged in the glamour of John Singer Sargent or found themselves captivated by the mysteries surrounding Vermeer. Nobody makes it quite as easy, though, as Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. This documentary begins with a murderer on the run; it ends with a disappearance still unresolved after 415 years.

Caravaggio was, as the titles at the start of this film delicately put it, not a man of letters. He was, however, a man who did a lot of talking, even when he would have been better off keeping his mouth firmly closed. He was infamous before he was famous, at least on a local level, and consequently there is no shortage of sources from which to gain an impression of his character. Nigel Terry made a meal out of this in 1986, in Derek Jarman’s sumptuous biopic. Here Jack Bannell takes on the role, conjuring up a remarkable physical resemblance to the figure we see skulking on the margins of so many dramatic scenes. Predominantly a stage actor, he also gives the painter a booming voice and declarative swagger that fit in well with the less salubrious stories about him.

This story, as we receive it, is framed by Caravaggio’s fateful journey aboard a ship to Rome, where he hoped to obtain a Papal pardon for killing a gangster in a brawl. The ship provides a beautiful opportunity to explore his techniques before they are spoken of, before we see them rendered in oils. Here are wood and water, rope and canvas in that very particular Mediterranean light, beguiling to the eye. They lead us into a series of paintings created over the course of his impassioned and eventful life.

Why did God give him these great hands, he muses, and yet curse him with a murderous anger? The film touches briefly on his childhood, his early apprenticeship as an artist, and his hitting the road, after his mother’s death, to reach Rome, the centre of the world, where he would hold a string of assistant jobs until he attracted the attention of his first wealthy patron, Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte. It isn’t hard to see how, given the unusualness as well as the beauty of his early work. Those skilfully composed still lifes, the lusciousness of the fruit an early hint at the direction of his work – but there with them, all those beautiful young men. Here the film departs from Jarman’s thesis. It establishes that the painter was bisexual, with various partners over the course of his life, but presents him less as indulging his own pleasures than as a man smart enough to understand the art market, know who had money and know what would appeal to them.

There are women in the pictures too, sometimes, including Fillide Melandroni (rumoured to have been the inspiration for that fatal brawl, though it’s not mentioned here). Caravaggio painted his friends, and found them in the sleaziest quarters of the city. We hear about his love of partying, of wandering round taverns with a sword. There is reflection of how his choices led to the capturing on canvas of ordinary people who could never have imagined being painted – and of their transformation into figures of myth and legend. Fillide as Saint Catherine and later as Judith Beheading Holofernes; himself as an ailing Bacchus. Occasionally, he painted the life of the streets as well. We see The Cardsharps; then there’s the curious allegory of Boy Bitten By Lizard. All this until his first chapel commission catapulted him to fame, and the rest is rather better-known history.

“Most of the documents we’ve got are police documents,” says one of the film’s several talking heads, explaining how it’s possible to track the course of his lie. That murder was hardly the first time he got into trouble. There is a distinct lack of theorising about the cause of his volatile temper (though theories certainly exist), but we see the passion in his paintings, in the violent subjects he chose and also in the scenes of tragedy, like Death Of A Virgin, perhaps inspired by the death of his own mother. We also see the ratio of light to dark shifting it his work, vivid and colourful to begin with but always tinged with shadow, that stunning chiaroscuro giving way to tenebrism, the blackness gradually dominating everything.

Throughout this time, because of the trouble he kept getting into, Caravaggio travelled, and we see many of Italy’s ancient ports looking little different today. These bursts of bright sunshine and azure sea make fitting interludes; we cannot spend all of our time in dark rooms. This also helps with the pacing, giving viewers time to breathe in what is, as usual, an informationally dense film. Detailed studies of complex paintings like The Martyrdom Of Saint Matthew, The Supper At Emmaus and The Seven Acts Of Mercy require viewers to pay close attention, and those viewing at home may wish to watch multiple times to be sure they’ve caught everything – though there is, of course, no substitute for seeing Caravaggio’s giant paintings, intended to inspire awe, in a cinema.

This also allows for a closer focus on the details designed to draw viewers in and make them feel like part of the action – one of several reminders that, despite the sometime crudity of his behaviour, the painter was keenly intelligent. A traditional cinema screen also places viewers near the front at the right height for properly appreciating The Beheading Of John The Baptist, which, as is explained here, was originally displayed so that those regarding it would be at John’s eye level, although he’s lying on the ground.

As the Biblical dramas of his late stage paintings plays out, from Salome With The Head Of John The Baptist to The Martyrdom Of St Ursula, Caravaggio’s own adventure moves towards its climax, and the film takes on something of the atmosphere of a thriller even as art historians point out that his conviction that he was being trailed by assassins may in fact have been paranoia. Directors David Bickerstaff and Phil Grabsky carefully balance the different possibilities as they balance the dramatic and documentary elements of the film. Newcomers to the artist’s work, or those who have had minimal exposure, will find themselves inspired to further explore the stories in the paintings themselves. For longstanding enthusiasts, it’s a bit of a whistlestop tour, but the rich biographical detail, some of it fairly recently unearthed, means there’s plenty to engage with – and, of course, it is a feast for the eyes.

Reviewed on: 11 Nov 2025If you like this, try:

Exhibition On Screen: Raphael RevealedHopper: An American Love Story

Klimt & The Kiss