Eye For Film >> Movies >> Barry Lyndon (1975) Film Review

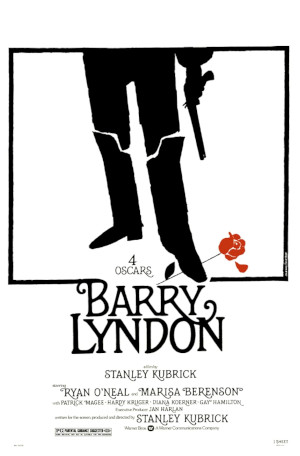

Barry Lyndon, released in 1975, is a sometimes whimsical, sometimes darkly comic historical drama from the director Stanley Kubrick. For a movie that won four Oscars it didn't do too well at the box office, and critical consensus about the film was mixed.

The first half of the film follows the life of the fictional Redmond Barry (Ryan O'Neal) through a series of misfortunes that propel him towards becoming a member of the aristocracy. It starts with Redmond, a young Irish lad, incompetent in love, duelling with the English officer Captain John Quin (Leonard Rossiter) over his cousin Nora Brady (Gay Hamilton, who coincidentally also appears in Ridley Scott's 1977 film The Duellists). After eliminating Quin, Barry flees - killing in a duel is murder after all - is robbed of all he has, and joins the army. It might have been a good. It has advantages: pay, respect, even rank if things go well. It's better than destitution or going home to face the music. The disadvantage is that it is the start of the Seven Years War, referred to sometimes as World War Zero. Events take their turn and Barry, attractive, intelligent and with a lax attitude towards the truth, is able to turn what seems like misfortune to his advantage.

Barry's rise from naïve boy to marrying into high society, becoming a Lyndon, is narrated by Michael Hordern. His words are warm and laced with deadpan wit. Those familiar with Peter Jones' voiceover in the BBC television version of The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy will know what it sounds like.

The second half of the film follows Barry's fall from grace. The qualities that once would get him out of trouble are now his undoing. He has ridden the randomness of events and gambled his way to the top, but now a combination of consequences and entropy will throw him down. The humour quickly leaches out of the film. The barriers between tragedy and the audience dissolve. No longer is it dressed for excess, but for a funeral. The change in tone is summed up by the intertitle that Kubrick uses as an epilogue:

It was in the reign of George III that the aforesaid personages lived and quarrelled; good or bad, handsome or ugly, rich or poor they are all equal now.

Kubrick leaves us with "The loan and level sands stretch far away."

Why did Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray's 1844 novel The Luck Of Barry Lyndon play badly with audiences? The collaboration with cinematographer John Alcott produces a film that is stunningly beautiful. The way that the pair are able to use natural light, candle light, to make a film that is reminiscent of William Hogarth paintings is ahead of its time. The sets and their dressing are beyond reproach and the acting is almost faultless. Is it that, at more than three hours, the film is overlong, or is it that the viewer is left with a narratively unsatisfying, if artistic, ending?

Kubrick badly misses the mark with this film, not in quality, but by a whole decade. It simply does not fit into the 1970s. Dog Day Afternoon, Taxi Driver and Jaws, they are its contemporaries, and it is nothing like them. It predates New Romantic music, Cinéma du look, the heyday of Merchant Ivory and the fourth wall breaking narration in The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy. It speaks of penthouse and pavement, 1980s excess and the grasping neo-liberal climb. In truth Barry Lyndon should be one of the best films of 1985.

Reviewed on: 17 Nov 2025