|

| Mr. Wilder And Me author Jonathan Coe with Anne-Katrin Titze: “I love Powell and Pressburger, so I was very happy to get in a reference to them.” |

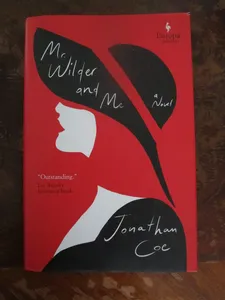

With Film Forum’s Written and Directed By Billy Wilder tribute, programmed by Bruce Goldstein (a three-week festival of screenings of over 30 films, most in 35mm, including Double Indemnity, Sunset Blvd., A Foreign Affair, Ace In The Hole, The Lost Weekend, Five Graves To Cairo, Some Like It Hot, The Seven Year Itch, The Apartment, Fedora, Howard Hawks’s Ball Of Fire, Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka and Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife), starting next week in New York, Jonathan Coe’s Mr. Wilder And Me is the perfect summer read.

|

| Jonathan Coe on Fedora: “The imagery always reminds me of that Georges Franju film Eyes Without A Face.” |

In the first instalment with the author we discuss Christoph Waltz as Billy Wilder in Stephen Frears’ yet-to-be-filmed adaptation of Jonathan’s novel; meeting Volker Schlöndorff just before the Covid lockdown; the images of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now staying with him; a connection between Georges Franju’s Eyes Without A Face (Les Yeux Sans Visage), Wilder’s Fedora, and Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In (La Piel Que Habito); Kevin MacDonald and Emeric Pressburger; Jaws in Venice and Frederic Tuten; People On Sunday (Menschen Am Sonntag); how a scene from Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound solved a narrative concern; the intimacy of first-person perspectives; tastes formed in youth and Halliwell’s Film Guide, compiled by Leslie Halliwell as “main reference book” for Seventies British cinephiles.

Jonathan Coe’s imaginative and savvy novel, Mr. Wilder And Me, centres on the making of Billy Wilder’s penultimate movie, Fedora, (starring William Holden, Marthe Keller, Hildegard Knef, Michael York) seen through the lens of a fictional Greek composer named Calista. A chance meeting with the famous director at his Irma La Douce-furnished bistro in Beverly Hills (designed by Alexandre Trauner who also worked on Wilder’s Fedora, Kiss Me, Stupid, The Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes, Witness For The Prosecution, Love In The Afternoon, and The Apartment) changes her life and it is with her that we travel to Greece and Munich for the shoot, and back to London, where she lives in post-Wilder times. In screenplay format flashbacks, Wilder himself becomes our guide to Berlin in the 1920s and expatriate life in Paris escaping the Nazi threat.

|

| Jonathan Coe: “I must have seen Don’t Look Now maybe the year I saw Fedora for the first time. These films are slightly linked in my mind.“ |

From London this past week, Jonathan Coe joined me on Zoom for an in-depth conversation on Mr. Wilder And Me and Billy Wilder.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Good to see you! On Easter, a dear friend of mine, my father’s wife Gabriele Rigó-Titze, told me about a book I had to read, because it has so many film references and she loved it. It was Mr. Wilder And Me and she was absolutely right.

Jonathan Coe: Oh great! So you read the American edition?

AKT: I did, the Europa Editions.

JC: And then you went and saw Volker Schlöndorff after that?

AKT: I met him at the Hedy Lamarr exhibit here. We’ve been in touch for many years and he was in New York in April and we talked about your book. You caught him right before Covid hit in March 2020, no?

JC: Yes, absolutely. Literally, I think, eight or nine days before we locked down in the UK I came back from Berlin after seeing him and then it all happened. It was a very memorable occasion. His house is very beautiful on a lake and has a very calm atmosphere and we had a long conversation about Billy Wilder that morning. The whole thing had a kind of otherworldly quality, you know. And then literally that was probably the last time I met someone outside my family for four or five months.

|

| Edith Scob in Georges Franju’s Eyes Without A Face |

AKT: I just had to read the first page of your novel and the film references hooked me in. The first sentence, “One winter morning seven years ago I found myself on an escalator” is very tale-like - a winter morning, seven, of all numbers, and the very memorable little girl or whatever she turns into from [Nicolas Roeg’s] Don’t Look Now. The red coat with the hood. Tell me a bit about that first page!

JC: First of all I figured that I was writing from the point of view of a film composer, someone who has spent her life watching films, making films, and thinking about films. So inevitably everything she saw would remind her of a film. But also that particular film, Don’t Look Now, has always been so powerful to me. Maybe because it’s one of those films I saw at an impressionable age when I was sixteen or seventeen, I guess. It was booked for some reason at my school film society. That’s where I saw it.

AKT: Wow, that’s an unusual choice!

JC: And the images of that film have stayed with me ever since. But I think there is a certain intensity to the film images that you see at that age. Maybe you become more inured to them from your twenties onwards, but thinking about it, I must have seen Don’t Look Now maybe the year I saw Fedora for the first time. These films are slightly linked in my mind.

AKT: The Seventies and the idea that what we see is not what we see - it makes sense.

JC: Because Fedora is a horror movie among other things, particularly in its last half hour or so when the plastic surgery happens and goes horribly wrong. The imagery always reminds me of that Georges Franju film Eyes Without A Face.

AKT: Oh yes.

JC: What’s the Almodóvar film with lots of plastic surgery?

AKT: I know the one you mean. [The Skin I Live In]

JC: If you happen to interview Almodóvar, do ask him for me whether he was influenced by Fedora! Because I’m sure he was. I mean the only country where that film survived and had a reputation in for thirty or 40 years was Spain.

AKT: Really?

JC: Yeah, first DVD I bought was a Spanish one in poor quality but it was the only way you could find it at that time.

AKT: Don’t Look Now also links to one of the moments in your book that made me laugh out loud, which is Jaws in Venice. The paragraph about Billy Wilder describing how Jaws has taken over Hollywood is absolutely wonderful.

JC: I feel a little bit guilty about it because I did steal that joke. There’s a New York writer called Frederic Tuten. Frederic and I are good friends, though we haven’t seen each other for many years. When I was over in New York and we had lunch together, he told me this crazy story about a former student of his, a creative writing student who had gone to Hollywood and I think landed some kind of deal with a three-word-pitch. Just saying Jaws in Venice! That always seemed such a hilarious idea to me that I tucked it away and decided to put it in a book sometime. And of course this was the obvious place.

AKT: It’s fantastic, it’s funny because it’s so visual.

|

| Jonathan Coe’s Mr. Wilder And Me (Europa Editions), collection Anne-Katrin Titze Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

JC: I think somebody should make it! I would pay money to see that film!

AKT: I would love to see it too, totally. The switch to screenplay format when you go into Billy Wilder’s life is very interesting in the middle of the novel. I recently had a conversation with Christian Petzold about his new film, Afire, and we talked about how there are no German summer movies since Menschen am Sonntag, People on Sunday from 1930.

And there is the scene you have with Wilder’s voiceover talking about how Robert Siodmak, and Edgar G Ulmer, and Fred Zinnemann are all sitting together in a café in Berlin. Tell me a bit about that format switch when you move back in time!

JC: Well, I sold the book to my UK publisher Penguin on the basis of a synopsis. I wrote in the synopsis that a big central portion of the novel would be a flashback to Billy Wilder’s years in Berlin and his flight to France and then to the US. And I have a very smart agent, a very astute woman called Caroline Wood and she read the synopsis and says: “Well that sounds great but how are you going to do that when the narrator of this book is Calista and she is a young woman in the Seventies? She won’t know anything about this. She wouldn’t have been there.” I waved that away and said “Well, I’ll think of something when it comes to it. It’s not a problem.”

Then when I got to the point in the book when I was writing the scene I suddenly realised, damn, she was right! How am I going to do this? Because the narrator I have chosen for this book can’t tell this story. And as so often, I started thinking about movies and I thought about, I think it’s Spellbound, the Hitchcock film which, if I remember correctly, as is often the case with Hitchcock films, has some incredibly artificial back projection. Gregory Peck and Ingrid Bergman are skiing down the mountainside and having a conversation with this totally fake scenery in the background.

AKT: That’s it.

|

| Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine in Billy Wilder’s Irma La Douce |

JC: I always remember that image and that came to me. And I said, okay, I can see here a dialogue between Wilder and his girlfriend while they’re skiing down a mountain done in that way. So I wrote the scene that way as a film script. That felt right and I thought, okay, that works, let me try and prolong this for a bit and let me see if I can write more scenes this way. And before I knew what happened, I had written 50 pages of the novel this way and I realised it was the obvious way to do it.

AKT: And Emeric Pressburger showed up out of the blue?

JC: Well, he was there as well at UFA studios. I love Powell and Pressburger, so I was very happy to get in a reference to them. One of the curious things about Billy Wilder, because he essentially is narrating this part of the story in the first person, is, I couldn’t find a written prose voice for Billy Wilder. And I realised the reason for that was that although, as you know, he started out as a journalist and a lot of his journalism has been reprinted recently, once he went to Hollywood, as far as I can tell, he stopped writing any kind of journalism, or anything at all in fact, except screenplays.

|

| Marthe Keller and Henry Fonda in Billy Wilder’s Fedora |

There are very few written fragments by Billy Wilder after he arrived in the States. He did the introduction, in fact, to the biography of Emeric Pressburger [Emeric Pressburger: The Life And Death Of A Screenwriter], but when I spoke to Kevin MacDonald, Pressburger’s grandson, about it, he said “Oh, he didn’t write it. We had to go to Hollywood and interview him and transcribe it.” So he never wrote anything except for scripts from the mid-Thirties onwards.

AKT: Talking of narrative positions, there are two moments in your book where you address us readers directly, if I’m not mistaken.

JC: I do?

AKT: Calista in parenthesis on page 202 says “But at heart (perhaps you know this already) I’m a sensible person…” The second time, on page 234, she says “I have a track record - as you will know by now - of making epic sartorial misjudgements.” I had to think of Christian Kracht, who suddenly, at one moment in his novel Imperium has a first-person comment on grandparents crossing through the heather. It’s these quick, unexpected shifts in a narrative that make one reflect differently on the perspective of the book.

JC: While I’m thinking how to answer that question, I’m just going to let my cat in through the back door. [He does so, and I can hear loud meows].

|

| Jonathan Coe on Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In: “If you happen to interview Almodóvar, do ask him for me whether he was influenced by Fedora!” Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: What’s the name of your cat?

JC: My cat is called Archie.

AKT: Named after Cary Grant?

JC: No, that would be nice. The naming is quite complicated. He’s my mother’s cat, she died three years ago and we inherited her cat and he is now ours.

AKT: I’ve had a string of cat appearances recently on Zoom. Christian Petzold’s cat also wanted attention and his was named after an Astrid Lindgren book, that’s why I asked. But back to the question.

JC: I don’t know really. I mean I don’t normally write novels in the first person. I’ve written 14 novels and three of them are in the first person. There are a lot of things I don’t like about the first person because it restricts your point of view. So as in this case when we came to the flashback scene I had to step outside it and find something different. Overall the thing I like about it is the sense of intimacy it gives you with the reader. And it gives you the opportunity to address the reader sometimes, if you like. In a way I’m surprised that I didn’t do it more often in the book because I found Calista’s voice quite quickly.

One of the nice things about this book is that it was one of the easiest and quickest books I’ve ever written. One of the reasons why it came quickly was that I found Calista’s voice quite quickly and felt comfortable inhabiting it. So yeah, it felt like a natural thing to do to address the reader directly now and then. I think it was an easy book to write because I’d been contemplating it for decades really. I mean, I’ve always wanted to write a book about Wilder. I assumed I would write a non-fiction book.

|

| Antonio Banderas with Elena Anaya in Pedro Almodóvar’s The Skin I Live In |

And then I wrote a biography, 20 years ago now, of a writer I very much admired called BS Johnson [Like A Fiery Elephant: The Story Of BS Johnson, 2004]. It was a really difficult book to write and a really un-enjoyable book to write. It came out well in the end but it took seven years and it was the most difficult thing I’ve ever written. In the end it left me with a feeling of dissatisfaction. I felt that the biography as a form had not let me get as close to him as I wanted it to. And I thought if I’m ever going to write about one of my heroes again then I want to do it in a novel, not as non-fiction.

AKT: A comment about another moment I liked very much in your book. When Calista and the Matthew guy go to the cinema in Paris, they are looking through Pariscope, and you list all the Wilder films playing with their French titles. There is Assurance sur la mort [Double Indemnity], La Garçonnière [The Apartment], and Embrasse-Moi, Idiot [Kiss Me, Stupid], a film I find disturbingly fascinating.

It all connects to memories of going to local cinemas [and seeing movies in translation on TV] and what different titles conjure up. Your Wilder says at one point about his view of cinema, that you have to give people something they are missing in life. Something a little bit elegant, a little bit beautiful. Are you thinking along those lines with your books?

JC: Yeah, I suppose so. I go to the cinema a lot and I love a lot of new movies, but essentially my tastes were formed, as I kind of hinted beforehand, in the 1970s, which means actually what I was watching were films from the Forties and Fifties, maybe Sixties, because that was mainly what was on television. So classic Hollywood cinema and European cinema as well was what was on British TV back then. That was the vocabulary of filmmaking that I grew up with.

Another thread that runs through the book, which is maybe a little lost on American readers, is for the Seventies British cinephiles, our main reference book was this big book called Halliwell’s Film Guide where all the entries were written by Leslie Halliwell, who had an incredibly reactionary and old-fashioned and grumpy attitude towards the cinema. The last good film that had been made was Casablanca or something, as far as he was concerned. He was constantly railing about the violence and the swearing and the sex in contemporary cinema.

Of course as a teenager I was desperate for violence and swearing and sex, so I was actively seeking out these films. But at the same time, something of his old-fashioned-ness rubbed off on me, I think. Because I read that book over and over. The strange thing about it is, I was reading verdicts on, and little mini essays about, films which I had never seen and couldn’t possibly see. So his encapsulation of them was more real to me than the films themselves.

AKT: Calista shares a lot of that.

JC: Yes, that’s true. Also I read a lot of interviews that Wilder gave in the Seventies and Eighties where he expressed similar feelings. His own attempts to get with it and try to fall into step with the film fashions and styles of the Seventies were not just a bit badly judged in a lot of cases but also very timid, really. There’s some mild nudity in his Seventies films, there’s a bit of swearing but of course when you look at a film like Taxi Driver or Dog Day Afternoon then he’s just barely dipping his toes in the water of what he could have done. And directors like Cukor and Ford who were making films at that time were having similar problems adjusting to how you do this.

|

| Jonathan Coe on recalling the skiing scene in Spellbound: “I always remember that image and that came to me. So I wrote the scene that way as a film script.” |

AKT: And that is one of the subjects of your book. Did you like Midnight Cowboy in the Seventies? Do you remember the reaction to that?

JC: I remember the reaction but I have never seen it.

AKT: No? Oh, you have to see it! And then you should see Nancy Buirski’s recent documentary on it and its times!

JC: It’s Schlesinger?

AKT: It is.

JC: I’m sorry I can’t update you on the movie adaptation [of Mr. Wilder And Me]. You know the wheels grind very slowly in the film business. We were hoping, they were hoping, to shoot in September this year and now I think it’s been put back six months, maybe more. We’ll see. I hope it still happens.

AKT: Do you see Christoph Waltz as Billy Wilder or were you surprised when you first heard about it?

JC: That was my suggestion, I mean it was and it wasn’t. It wasn’t because I suggested it that they did it, but obviously when he was their choice I was delighted that it had been my initial suggestion. I think he would be great, so I do hope it happens.

AKT: So do I. Thank you for this!

|

| Written And Directed By Billy Wilder at Film Forum in New York Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

JC: Thank you so much.

Coming up - Jonathan Coe on Al Pacino, Marthe Keller and the infamous Munich cheeseburger, how a dumpling was changed for the German edition of the novel, overdressing and underdressing, yearning for unattainable movies, Orson Welles and The Other Side Of The Wind, Wilder’s Private Life Of Sherlock Holmes and what is lost forever.

Written And Directed By Billy Wilder at Film Forum in New York starts on Friday, July 14 and runs through Thursday, August 3.