|

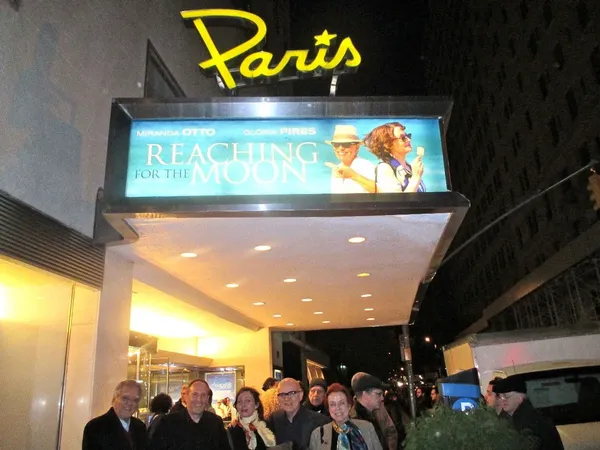

| Matthew Chapman, Anne-Katrin Titze, Bruno Barreto, Lucy Barreto under the marquee of The Paris Theatre. Photo: Ed Bahlman |

The Paris Theatre, one of the most prestigious cinemas in the US, had a full house for a Saturday night screening of Bruno Barreto's incandescent Reaching For the Moon, starring the formidable trio, Miranda Otto, Glória Pires and Tracy Middendorf. We began the post-screening discussion with numbers as producer Lucy Barreto, director Bruno Barreto, and co-screenwriter Matthew Chapman spoke about the film's coming of age in a 40 minute conversation with the participation of an enraptured audience.

The ribbon for the opening of The Paris Theatre was cut by Marlene Dietrich in 1948. Barreto celebrated his own anniversary - 35 years ago his film Dona Flor And Her Two Husbands opened at the Paris in 1978 and an after party was held at Studio 54 with guests including Robert De Niro and Liza Minnelli.

Lucy Barreto recounted her own meeting at a luncheon in the Fifties with the legendary couple, American poet Elizabeth Bishop and Brazilian architect Lota de Macedo Soares. The rights for the story were purchased by her 18 years ago. And now, in 2013, we learn what Woody Allen and Pedro Almodóvar films have in common with Reaching For The Moon in Brazil.

|

| Packed house at The Paris Theatre for Reaching For The Moon Photo: Ed Bahlman |

Here are some of the highlights from the evening.

Anne-Katrin Titze: I was told by Bruno during my conversation with him at the Tribeca Film Festival that you met Elizabeth Bishop and Lota de Macedo Soares in person in the late Fifties. Tell us how the journey of this film began.

Lucy Barreto: I met both of them around ’57, ’58 at a lunch at Samambaia… I could look at them and they were all the time looking at each other, Lota to Bishop, and Bishop to Lota. Even when they were across on the other side of the room, they would look at each other, they would smile ironic smiles, and the film in a way, has this atmosphere, it’s a film about emotions, feelings.

The first thought of turning the story of their relationship into a movie came decades later:

LB: It was Christmas 1995. I got the book Rare and Commonplace Flowers from the editor. I read the book in one night and the day after I called the writer, Carmen Lucia de Oliveira, and I told her I want to do a film with the book. I want the option and I assured her that I will produce this film. Glória [Pires as Lota] was part of this project from the beginning.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Bruno, you were reluctant about the project at first. When did you become interested?

Bruno Barreto: She [Lucy Barreto] gave me the book. I wasn't interested. I didn't read it. She then offered it to Héctor Babenco, you know, who did Kiss Of The Spider Woman (1985) and he didn't read the book either. After seeing a performance at Vassar by my former wife about Elizabeth Bishop, called A Safe Harbor For Elizabeth [written by Brazilian playwright Marta Góes] at the Powerhouse Theater at Vassar. It came down here on 59 Stages [Primary Stages at 59 East 59 street]. I knew it was pretty much the same story, the same characters. I started to get the itch to dig into that story. Then I read the book for the first time in 2004 and then Bishop's poetry. Bishop didn't write a lot, she re-wrote a lot. She was so critical of her work. That's why her production wasn't very big, very extensive. It took me over four years, from 2004 to 2008 to find an angle. Why do I want to tell this story? What do I want to tell this story for? To talk about what? After reading Bishop's poetry, most of her writing, not everything, talked about loss. Some poetry and prose more directly than others. I didn't want to do a biopic or another film about another tortured artist. I wanted to tell a love story about how a weak, dysfunctional, alcoholic drifter, Bishop, gets stronger and stronger because she deals with loss. And how the winner, doer, strong Lota [de Macedo Soares] gets weaker and weaker because she just pretends, avoids, ignores loss. I thought this reversal of roles was very very interesting. That's when I really decided to do the film in 2008 and I started to work on the script.

|

| Matthew Chapman with Anne-Katrin Titze in the lobby of The Paris Theatre Photo: Ed Bahlman |

AKT: Matthew, please talk about how you, as a writer, were working with Pulitzer Prize winning poet Elizabeth Bishop's texts. You did a wonderful job of not simply illustrating poetry. How did you make your own poems out of her poetry?

Matthew Chapman: Well, I think the poetry in the film is really Bruno's incredible mise-en-scène, the way he does his shots is a poetry on its own. If I brought anything to this film - I'm not very reverent. Most people who write biopics are reverential toward their subject. I don't have a lot of reverence in me. While I was respectful of the truth, I wasn't so reverential to the characters.

At this moment, the Paris Theatre's bright spotlight is suddenly turned on, blinding Matthew, who doesn't miss a beat. Here is his response to being singled out in the spotlight.

MC: I promise, I didn't do it! I just tried to write a good script!

The audience bursts into laughter and applause. We all cover our eyes from in front of the stage as this artificial moon is demanding reverence.

MC: I just tried to write something that was human. What I got was a very good script but it didn't have any lines [in 2012]. So I added a lot of humor to the characters and I think I brought it to life. Bruno and I worked very hard together.

BB: What I thought was brilliant, was to bookend it with the poem. We start the film with the poem she shows to Robert Lowell [Treat Williams] and he says it's not totally there yet. That is not true at all. That's where the fiction begins. The script had voice-over and Matthew kicked the voice-over out totally, because it wasn't necessary and he turned it into dialogue and speeches Bishop gave. Everybody who read the many drafts we had, said this is Lota's story. She is the driving force. I thought, no, if you have a love story, you got to have a balance. Matthew managed to make Bishop empathetic but not sympathetic. We would have betrayed the essence of who she was because she made no effort at all to be liked or loved or anything. She wanted to be liked or admired by what she wrote, her poetry, but never by her behavior. Matthew helped me not only during the script phase but also during rehearsal and during the shoot, too. Miranda [Otto, who plays Bishop] was very very brave because she didn't fall into that trap that many Hollywood actors fall into and that is to make the character likable.

At this point we opened up to questions from the audience. These are some of the subjects covered.

|

| Bruno Barreto, Lucy Barreto, Matthew Chapman in the spotlight with Anne-Katrin Titze Photo: Ed Bahlman |

On the use of modern architecture and landscape architecture as an additional character in the movie:

BB: Lota never studied architecture. She was self-taught. She was actually very close to [Alexander] Calder. He went to Brazil in 1948, four years before Bishop. It was a challenge because I didn't want the film to be precious. It was important for the film to have a look. It was important that the architecture and the design play a role in the film but not to stay in front and become more important than the characters.

On the production design challenges:

BB: The Fifties are so 'in' right now. José Joaquim Salles was the production designer. It was very hard to make it special. There was one moment I walked into a set and there was a couch that was in the waiting room of my dentist's office. It wasn't wrong. It was completely period but so 'in'. We got to make it the Fifties that nobody had seen. It ended up a great challenge for production because it cost a lot more.

Lucy Barreto nods in agreement.

On the house in the film and the original house:

BB: The owner [of the real house] wouldn't even allow us to visit. People are very protective of Bishop and Lota. It's almost like a secret society. She is a very rich woman and she didn't allow us to visit. So we found this house by Oscar Niemeyer and ironically, the landscape is by Roberto Burle Marx, who was hired by Lota to design the landscape of the park [Flamengo Park in Rio de Janeiro]. All we had to do was build the studio. That was all a set. The owner of the house liked it so much he wanted to keep it. He couldn't, because two months later it would be gone because it was a set.

On Mary Morse, the adopted child, and The Art of Losing:

BB: Mary [the third party to this relationship] for me is the Art of Losing. I wanted to call this film The Art of Losing. And I couldn't convince her.

Bruno points to his mother, Lucy Barreto, who sits next to him in front of the stage and takes the microphone out of his hands.

Lucy Barreto: No! Nobody wants to lose anything!

The shimmering eyes of dozens of owls punctuate the dark jungly forest, while the two contrasting souls drive towards their first kiss. Reaching For The Moon has the scope of Out Of Africa and "Brazil is not for beginners," as Bishop will later conclude.

BB: I thought it was a great title. Look at the poster - To win, you gotta know how to lose - The Art of Losing… Then I came up with Reaching For The Moon which is an okay title. Anyway, Mary ended up dying in 2002. She and Lota had adopted more children, there were four children. Monica/Clara was the first one. She is alive, she is 53 and we interviewed her. The scene where the owls start to sing [was hers] and we turned that into Lota and Bishop's.

|

| Bruno Barreto's Dona Flor And Her Two Husbands at The Paris Theatre in 1978 Photo: Bruno Barreto |

On the reception of the movie in Brazil:

BB: The film was well received in Brazil as an art movie. It did what the Woody Allen films do, or Almodóvar, or films like that. There was one theater in the biggest town close to where we shot. The film was supposed to play there. Locals who had worked on the film went to the theater and there was a sign saying the print hadn't arrived. We called the distributors and they said, no, we have a piece of paper here confirming that they did receive the print. It turned out the theater owner didn't want to play the film because of the theme.

On the strong emotional impact:

Matthew Chapman: You could advertise this film as 'First Lesbian Trio Adopt a Baby', that would be the tabloid version. Bruno was very intent that we shouldn't focus on the gay politics or in fact the politics of Brazil and just concentrate on the human theme. It's interesting that one never thinks those thoughts that I just said. It was a very amazing thing that these women had a family so early as a gay couple.

About the ending:

Lucy Barreto: That is the truth. She [Lota] committed suicide.

Bruno Barreto: Elizabeth Bishop died in Boston of an aneurysm in 1979. She was 68.

Bobby Vinton's Blue Velvet plays on the radio, the airy modernist buildings fold snugly into the lush Brazilian landscape, and the story has only just begun in Reaching For The Moon.