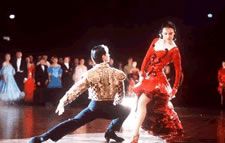

Sally Potter and Pablo Veron in The Tango Lesson Photo: Georgui Pinkhassov/Sony Pictures

“Someone said the essence of cinema is movement. All directorial decisions are also choreographic ones. Where the camera should be, and should it be moving or still: where the bodies are, and what and how they are communicating. Even the flicker of an eyelash in a strictly realist piece of cinema is also a piece of choreography. And film exists only in time – like dance.”

Sally Potter was speaking in relation to her film, The Tango Lesson. Dance and film, seemingly worlds apart, both use movement as their geography, their space, their means of communicating. Dancers use movement in physical space. But the camera uses movement over and beyond physical space. It moves between whole continents in the blink of an eye. It crouches, glides, performs a jeté not just through the air but through time. A dancer can begin moving today, or tomorrow, and be transported, finishing the step in a bygone era or the costume of a distance place. Editing and montage are cinema’s choreography.

Whether filmmaker or dance performer, both seek to take us on a journey. To bring out a special magic from inside us. When did you last feel that? When did your heart dance? Your spirit soar?

“Ah, I think to myself. If only I could learn to live the way I dance,” says Potter. “If only I could learn to work (to write, to direct) without pretension and self-consciousness, strong and sure and vulnerable and open, all at once – sweating, working, at my own limits and yet easy, flooded with pleasure.”

Dance-film/film-dance was, maybe, born from an unlikely coupling in 1894. Thomas Edison, inventor of motion pictures, ‘tripped the light fantastic’ with flamboyant dance pioneer, Ruth St Denis. She did a skirt dance. Dance becomes a visual heartbeat. In musicals, in advertising, in pop videos. Film also becomes a research tool. Dancers can see themselves. Dance teachers can use video libraries as a teaching tool. Choreographers and installation artists can push boundaries.

Through film, dance reaches a wider audience. Through dance, film leaps from the screen.

Increasingly, film-dance collaborations, like Edinburgh’s Dance:Film Festival or the Dance Films Association, bring different types of audiences together, challenging the ways we view each medium. We invite ourselves to be been entertained, educated and inspired by the whirlwind embrace of lightly stepping feet and smoothly synchronised cameras.

Bringing dance and film together elicits challenges that can prove very positive. The doyen of choreographers, Merce Cunningham, said working with dance on film made him more aware of using space precisely. When dance goes to camera, positioning dancers within the frame needs to be very exact. Cunningham’s awareness of accurate positioning was increased on going back to the stage.

A theatre audience’s view, owing to the laws of perspective, makes the distant back of the stage seem smaller than the front. But the camera’s view is the reverse: there is a wide area for movement further away, whereas dancers close up have only a small space before they move out of frame. This leads to another dilemma: how far away does the dancer need to be to keep the whole body in view?

Fred Astaire would compose shots very much as if the screen were a stage. The camera would be positioned in an ‘ideal seat’ in the auditorium then simply pan to follow the dance. Gene Kelly, on the other hand, would use the camera’s ability to move much more. His dances would be seen from different angles, or coming in close for emphasis before going back to a more panoramic shot.

When these dancers were contemporary screen idols, the screen format was similar to the narrow oblong of a standard television set. A dancer in full view occupied a sizeable portion of the screen width. But with the advent of CinemaScope, the screen becomes much wider. New techniques are necessary if the dancer is not to be swamped by the extra detail on either side.

Dance technique informs film, and film techniques extend the possibilities of expression in dance. Early studies in ‘natural’ dance by Isadora Duncan, in which the dancer finds and projects an ‘inner reality,’ were mirrored in the techniques of ‘method’ school actors. Sergei Eisenstein, the revolutionary theorist in the early days of film, absorbed ideas from the world of dance: "The rhythmic organisation of a role entailed the impulsive, reflexive link between thought and movement, emotion and movement, speech and movement." Delsartian theories of gesture, and Dalcrozian ideas of rhythm, were being reinterpreted not only in the theatre but for early experiments in montage.

But cinema soon repays its debt to dance. Fortunato Depero, a futurist commissioned by Diaghilev (founder of the Ballets Russes) would write, "It is necessary to add to theatre everything that is suggested by cinematography." Experiments with light, time shifts and simultaneous use of different parts of the stage would follow.

Cinema is pre-eminent in mastering time. Flashbacks. Flashforwards. Pacing. Freeze frames. Slow and fast–motion. Or visual foreshadowing, in which a visual symbol early on suggests an action that will take place later. While very straightforward in film, it can also transfer to dance. A comedic or improvised dance, an emphasised gesture or expression, can be recalled by a polished version that follows. Consider the ‘Pick Yourself Up’ polka in Swing Time, or the early Paso Doble stomps in Strictly Ballroom.

Both film and dance use rhythms as a powerful psychological component. Dancing releases endorphins. Repetition of movement or image can create a hypnotic effect. Primitive cultures use dance to induce possession (as seen, for instance, in Deren’s Divine Horsemen). The predictable dance intervals of Bollywood films guarantee the audience an emotional high. Om Shanti Om, a big Bollywood film, has almost a dozen song and dance numbers of around five minutes each. Advertisers also use repetition till we believe we want another yet anti-ageing cream. Snake hips to snake oil.

Do you ‘dance as if no-one’s watching?’ And what if you perhaps keep that inner high when someone is watching with a camera... Maybe we’ll see you at the next dance-film festival...?

The Dance:Film Festival runs in Edinburgh from May 21 to 30. You can read our coverage here and view the full schedule of films and events on the official site.