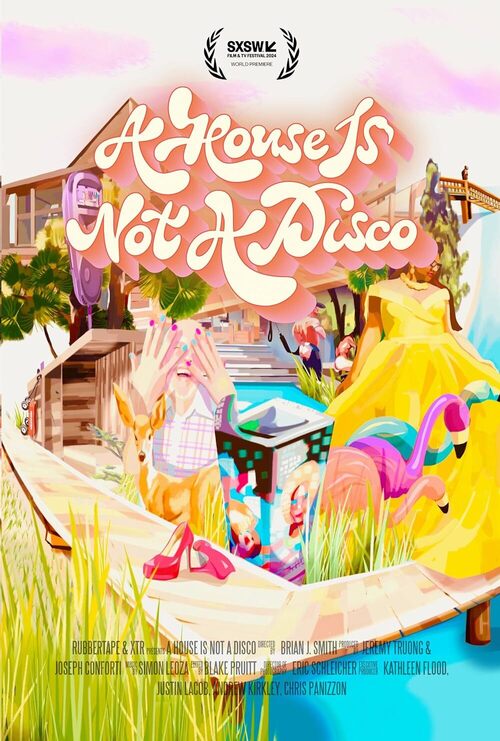

Eye For Film >> Movies >> A House Is Not A Disco (2024) Film Review

A House Is Not A Disco

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

It’s a legendary place, a place so talked-about in LGBTQ+ circles for so long that to those who haven’t been there in person it seems like a dream, but Fire Island Pines has never been captured on film like this before. Even if you’ve been a regular there, you might not recognise it as first presented: off-season, a haze of drizzle in the air, the streets empty, under a blanket of silence. It’s so cold in winter, says Brian J Smith’s first interviewee, that even the deer leave.

Screened as part of 2024’s South by Southwest, Smith’s film is an insider portrait of the place and a love letter composed on behalf of the community to which it has meant so much. “I’ve been here almost continually since 1968,” says that first contributor. “Everywhere I look I see stories.” He and his partners are preparing to party: uncovering the sofa and the pool, fixing up harnessing equipment, hoisting the rainbow flag. “It feels like gay summer camp,” says someone else, and as holidaymakers slowly begin to arrive we see the joy on their faces, a sort of lightness, the pressures of day to day life cast away.

There is a short history lesson for the uninitiated, an explanation of how this small town on a little strip of sand, just 49 miles from New York City, was adopted by the gay community in the aftermath of the Stonewall riots, at the height of disco, during the sexual revolution. It does not escape notice that some homophobes are obsessed by the notion of putting all the gays on an island (the Nazis actually tried it), but they probably didn’t intend this result. Although the film addresses lots of different topics, there are themes which come through consistently: the excitement of sexual opportunity, the sense of freedom to fall in love (for good or ill) and the delight of just being able to wander around and interact with strangers without one’s sexuality being a big deal.

The magic doesn’t work for everyone, and it’s good to see Smith, who doesn’t hide his personal attachment to the place, making the effort to include those who experience it differently. It’s a spiritual place, a place of transformation, says a trans woman who found that it gave her the freedom to discover herself, but another says that since her transition she has felt a lot less welcome. A Black guy with long hair expresses similar feelings. There is a discussion of prejudice based on looks, an issue for the wider community too. As people have grown old whilst participating in and hosting parties there, ageism isn’t as obvious as in many LGBTQ+ venues, but there’s still a sense that some of the younger generation of attendees are smug and disrespectful. There’s a cultural difference there too. They don’t know what it was like to live during the early years of AIDS; they don’t know the price that their forebears paid.

For older people visiting this place, ghosts are inescapable. The dead are missed, but there’s a sense that they are still at the party – and, of course, their influence is present in what they helped to build. For many people who suffered horrific losses, the Pines was the place they came to for support and recovery, and the community has inherited a remarkable strength and resilience as a result. It’s here that the film finds something of much wider social significance, as it looks at how this different way of thinking has affected the community’s response to climate change.

As the seas rise, storms increase and tidal surges grow stronger, Fire Island is right in the front line. The beach is being eaten. Sometimes a whole day’s work spent preparing for the next day’s events can be washed away overnight. The community does the work anyway. This sense of ephemerality doesn’t scare people off. It simply makes it all more precious. There is a sense of living in the moment but for the future, a deep connection with nature and a willingness to face whatever happens together, to build and rebuild as often as it takes. One cannot help but feel that this is something everybody will have to adjust to in due course.

How does one cope with such pressures? It might not help to live in a society which sees no value in anything but productivity. If there’s a final message to this very specific yet wide-ranging film, it’s that it’s important to party. Happiness matters. As the sun slowly sets, music blares out from a pavilion and a vast crowd dances on the sand. A House is Not A Disco feels like a glimpse of a possible future. The Pines just got there first.

Reviewed on: 25 Mar 2024