Toby Perl Freilich, director of Maintenance Artist (a highlight in the 24th edition of the Tribeca Festival) and producer Judith Mizrachy (DW Young’s Uncropped on the universe of photographer James Hamilton) were joined by music producer and 99 Records founder Ed Bahlman for an in-depth conversation on the extraordinary documentary that chronicles the challenges for Mierle Laderman Ukeles as the first-ever Artist-in-Residence at the New York City Department of Sanitation.

|

| Mierle Laderman Ukeles - Touch Sanitation performance, 1979-80 |

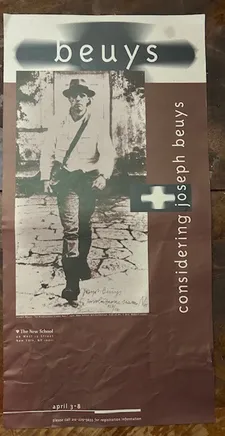

We start out discussing Mierle’s monumental Touch Sanitation project, the score by Clare Manchon and Olivier Manchon, and the work of editor/co-writer Anne Alvergue and graphic designer Matt Eller. Clips from Julian Rosefeldt’s Manifesto, starring Cate Blanchett, and Joseph Beuys in his I Like America and America Likes Me address important aspects of her career. The support from Hannah Wilke and Ana Mendieta, Ed meeting Mierle in the Seventies at Martha Wilson’s Franklin Furnace, and the controversial reaction from some of the members of West-East Bag to her Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969 and more all came up.

Her entirely new kind of public art changed people’s perceptions of maintenance work. Whereas her idols, Marcel Duchamp, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock, “didn’t change diapers,” Mierle was a mother, who included the fact in some of her performance pieces. Snow workers in a particularly cold area in Japan were celebrated by her during the warmer months with the staging of a ballet for snow ploughs. The film works as an appeal that doesn’t let go. Next time you come across workers wearing vests of “emergency red orange and fluorescent safety green” you may find yourself tempted to thank them for their help in holding this fragile world of ours together.

Ed Bahlman on the hottest June 24th in New York City history (inspired by Mierle Laderman Ukeles and her Touch Sanitation performance shown in Maintenance Artist) offered a bottle of cold water while shaking hands and thanking sanitation worker Kevin Gonzalez.

|

| Ed Bahlman thanks sanitation worker Kevin Gonzalez after offering him a bottle of cold water on the hottest June 24th recorded in NYC history Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

Mierle sums up her goals as follows: ”I want people to understand the conditions of human beings living on the earth. If we want to live here, we must learn to cherish the work of taking care. That is in our hands. We are all a maintenance worker.”

From New York City following the Tribeca Festival World Premiere of Maintenance Artist, Toby Perl Freilich and Judith Mizrachy joined us on Zoom for an in-depth conversation on the documentary and Mierle Laderman Ukeles.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Hi Toby!

Toby Perl Freilich: Oh, nice to meet you!

AKT: How was Tribeca? How was your screening?

TPF: It was thrilling, exhilarating, nerve rattling. And it's been one of those weeks. I feel like I'm eating the fruit off a tree I planted eight years ago when I started this film. It's just exciting to finally see it.

AKT: And Judith is here now. Then we are complete.

Judith Mizrachy: Hi.

TPF: Hi, Anne-Katrin was just nice enough to ask how the Tribeca launch has been, and I told her what an exciting week it's been!

JM: It's been amazing. It's been really great.

|

| Toby Perl Freilich - Tribeca Festival Maintenance Artist world première Photo: Judith Mizrachy |

AKT: That's wonderful. Very nice to meet you, too, Judith.

JM: Nice to meet you. I remember when you were talking to James [Hamilton on DW Young’s Uncropped] but I don't think I was on that call. So it's nice to meet you.

AKT: Yes, this is perfect. Now that Tribeca is winding down. Maintenance Artist - I love how you begin the film. New York, 1979 and how Mierle introduces herself to the sanitation workers and we see their faces. It makes the audience think: Where is this going? What is going to unfold? It's a perfect entry point that makes people curious who don't know her and makes those remember who do know about her art. Can you tell me a little bit about the beginning?

TPF: You know, beginning a film is always hard. Many filmmakers leave it to the last thing. We flirted with different introductions. We wanted to sort of set the stage, like, why is the viewer watching this film? What is going to happen? And we knew that we had to start with the surprise of Mierle, the sort of incongruity of an artist and the Department of Sanitation as a hook. But it wasn't clear exactly how. There's always the compulsion to work chronologically and start with the beginning. Also, I think it's very hard to make a drama out of somebody's life. Some people have very dramatic lives for better and for worse. But when you're telling a biographical story, it's difficult to find the dramatic moment. So we broke the chronology to start with what is probably the most dramatic moment which is her iconic Touch Sanitation performance [1979 - 1980].

AKT: The split screen and the music that is very Shaft, makes it all very Seventies.

|

| The Social Mirror, 1983 installed at the Queens Museum, 2016 Photo: Hal Zhang, courtesy of Maintenance Artist |

TPF: Okay, so full credit goes to the film's editor and co-writer, Anne Alvergue. That was entirely her conception and execution, although we did have a wonderful graphic designer, Matt Eller, who kind of refined Anne's concept. But Anne was just critical in telling this story. I had a lot of ideas, a lot, a lot that I wanted to say. There was a lot of material. And Anne really helped shape the story and how it was told.

AKT: Because that beginning makes it almost, as you said, dramatic, almost like a thriller. And then the comical elements also come in when we first go into the Department of Sanitation and she is listed on the board as “rtist in residence”! The A had fallen off!

TPF: The A is missing! Well, those were the conditions she was working under. I don't want to call the Department of Sanitation a stepchild of city government, but it's not the police force. It's not the sexiest division of New York Government.

AKT: Yeah, so much about maintenance and maintaining the the plaque there! You show her conflict in a way, throughout the whole film and throughout her life with maintenance. We hear her state: I don't want to do cataloging. I want to make art! And cataloging is maintenance itself. So that's fascinating. Judith, I would like to know how you got involved, how this came about for you!

JM: Yeah, I had worked with our editor on a previous project. She's the one that connected me with Toby. And when I first heard about Mierle, I did not know who she was. As soon as I saw some footage and an early cut I was completely just blown away. I couldn't believe I didn't know who she was. I’ve said this to Toby, in the scene in the film where she's talking about her epiphany, when she writes the manifesto, I mean when I first saw that, I felt like I was having an epiphany. It really kind of continues to reshape the way I think about things. So I was immediately hooked, and I wanted to be part of the project.

AKT: Yes, the whole idea of maintenance art, of how people see maintenance work, goes so much beyond just her individual artworks, which becomes part of the art. It has this gigantic impact. You bring up the manifesto. I loved Julian Rosefeldt’s Manifesto. I loved the installation [at the Park Avenue Armory, December 7, 2016–January 8, 2017] as well as the film with Cate Blanchett about it. By the way, I went to university with Julian's brother; we were in a Hitchcock seminar together. Manifesto is a beautiful inclusion. Were you familiar with Manifesto before working on the film?

JM: I hadn't been familiar with it. So I really discovered it through working on this film. Meeting Toby was fantastic, and I just loved her approach to the material. And then I had worked with Anne and knew that she was going to be such a great storyteller collaborator as well. So but yeah, I didn't know about it. I'm a lifelong New Yorker, so I feel like, how did I not know about this? One of the great things about being a documentary filmmaker is how much you learn all the time about people in the world.

AKT: As a film journalist you also get to take in all these wonderful things. Toby, the Manifesto is such a lovely addition, also the specific little Cate Blanchett moment.

TPF: Yeah, I started working on this film in 2017, and I think the Julian Rosefeldt Manifesto came out around then, if I'm not mistaken.

AKT: A little before that, yes.

TPF: I obviously was working on the film and then there was this exhibit in Israel at the Israel Museum and they invited Mierle to the exhibit, which was about Manifesto, the film about Julian Rosefeldt’s Manifesto. So it's a perfect opportunity to film the event and the film within the film so that was irresistible. That was a really happy coincidence that ended up being in the film.

|

| Cate Blanchett in Julian Rosefeldt's Manifesto at the Park Avenue Armory Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

And that Cate Blanchett actually acts out a section of Mierle’s manifesto. Her manifesto is a bit of esoterica, right? I mean, as Judith said, here we are, I'm a lifelong New Yorker, she's a lifelong New Yorker. I hadn't heard about Mierle or about her manifesto. I'm a filmmaker, but I did study art history back in the day, and here was an opportunity. To me the notion of a manifesto, all I kept thinking of was the Communist Manifesto, and I asked Mierle and she said, well, you know, Dada had a manifesto.

AKT: The Futurists too.

TPF: Manifestos have played their part in the history of art and in the history of politics, and it was a way of telegraphing what Mierle has always thought about as revolution. You know, she wants to start a revolution, and that was what maintenance art was for her. How do you start a revolution? Best you issue a manifesto! So to me that was the connection to the Communist Manifesto, even though she said that it was more the art history manifestos.

But I must say I found that very intriguing, because it wasn't just. I mean she calls it, something, don't quote me exactly here, but like a sculpture that's in four pages. So both a work of art, but also a declaration of war on the prevailing culture.

AKT: Most of these manifestos were also by males. In the entire Manifesto installation she was one of the few women. I remember talking to Julian about Donna Haraway's Cyborg Manifesto not finding its way in, and he said, yes, yes, I know, great omission, sorry!

TPF: Hey, it's good that you said that!

AKT: You also bring up in the film how she was different from other artists, feminist artists at the time, who many of them undressed and addressed the male gaze. There was also during that time a lot of breaking of things and her work is the opposite. It's not about destroying. She's breaking in different ways. She's breaking by maintaining.

|

| Touch Sanitation performance, 1980 Photo: Marcia Bricker, courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York |

TPF: I love that you are saying that because I felt that very strongly, that when I hear revolution it’s let's just break everything. Well, that's all well and good. But one of the taglines that we took from the manifesto was after the revolution, who's going to pick up the garbage Monday morning after you finish destroying the prevailing order? Who's going to pick up the garbage? Who's going to make sure that the world continues, and certainly a lot of Sixties art, late 20th century art, was very iconoclastic.

It was trying to just break, break, break, which was necessary and courageous. But I thought what was interesting about Mierle was that it wasn't just about breaking things. As you said, it was also about saying, how do we keep? How do we preserve? How do we conserve? And certainly, when it came to the environment, that was wholly in tune with that moment as well.

AKT: Another moment that I loved is when, in reference to Beuys and his I Like America and America Likes Me, coyote event installation [René Block Gallery, 1974]. And Mierle comments later in the film: “He swept!”

TPF: And then she says: “I swept!”

AKT: Judith, did it inspire you, too, in some respect beyond the film?

|

| considering joseph beuys at The New School. 1995, collection Ed Bahlman Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

JM: Absolutely, I mean, first of all, this is a change of perspective. It happens in your head. I'm a mom, and I find all her stuff about motherhood inspiring. As somebody who's working as a filmmaker and is also a mother, and trying to reconcile the two things. Her feminist vision is complex. It cracks me up in the film when she said, “I didn't want to dress for success”. That wasn't her vision of feminism. And then, of course, when she's talking to the men, and says “they think we're their mother, the sanitation men say.” It's complex, it's interesting. And it's constantly making me think about new things.

AKT: The sense of self-worth that is brought up in the context of shaking the hands of all the people in the city who handle the garbage. All of this is very important and has become even more so. The whole idea of maintenance of our planet, I mean, composting, garbage disposal, recycling, all that now in the present is so important for us.

TPF: About the shaking hands, I mean, the hand is a bit of a motif in the film. She put her hand on her husband's hand. He was doing the gardening, the shaking of the hands, the gloves that appear in her work, the used work gloves. There was something about the human connection, especially with a sector of the workforce that are shunned and almost regarded as contaminated because they handle garbage, and she was like, take your glove off! I'm not wearing a glove. This is an act of appreciation, not disgust. So that was for me extremely moving because she saw her work as so much about that human connection. That says, I see you. I recognise you. I appreciate what you do. I thank you.

AKT: Yes! And even the snow plows in Japan seem to be shaking hands in ballet.

TPF: That's true. That's true. Yeah.

AKT: I have somebody here who wants to say hello briefly to you, who knew Mierle in the Seventies, music producer and founder of 99 Records, Ed Bahlman.

Ed Bahlman: Hello, good morning. Great job in showing us the late Seventies New York, just with the sanitation workers and Mierle. I remember meeting her then at Franklin Furnace. I knew Martha Wilson very well.

TPF: Oh! Hi!

|

| The Social Mirror on the streets of New York City, 1983 Photo: courtesy of the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York |

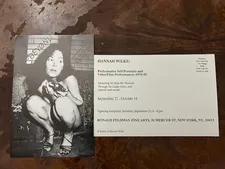

EB: Being there. One of the guys who went there, you know. [Eric] Bogosian, Karen Finley, that whole crowd. I'm glad Hannah Wilke was appreciative of her work. Because I liked Hannah very much. And also pointing out Carolee Schneemann was not.

TPF: Carolee was not appreciative? She didn't like Mierle’s work, you're saying?

EB: I think in the film there's a point made with a photograph.

TPF: No, I don't. She's never named as someone who didn't like her.

EB: You show something with her, though, an image?

TPF: Yes, she's in the film. I think the moment you're referring to is where she's in the middle of her Touch Sanitation project, and she starts getting blowback from the feminist artists. There was a feminist arts group called WEB - West-East Bag, and she never names which women artists gave her trouble. But what she does say is that Hannah Wilke and Ana Mendieta came up to her after this meeting, where she was being criticised and said, they're wrong. What you're doing is important and necessary. And you go, girl!

EB: Yeah, perfect.

TPF: You have to tell me your name again, because I'm going to want to tell Mierle, she's going to be very excited.

|

| Hannah Wilke, 1996 - Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, collection Ed Bahlman Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

EB: Ed Bahlman. I founded 99 Records, which was also a shop [at 99 MacDougal Street]. James Hamilton knows, we talked on Zoom together, and I also knew Thurston Moore very well before he was in Sonic Youth.

TPF: Oh, wow!

EB: It brought tears to my eyes when she was telling the children to wave to the sanitation workers on their block! Growing up in Brooklyn in the Fifties and Sixties, we knew the people who picked up the garbage and they knew us kids, and they would wave to us. There was no tension like there is now. So your film is even more relevant nowadays.

TPF: Thanks. Yeah, we think so. I mean, we're excited. I grew up in New York, in Queens. I was born in Brooklyn, but grew up in Jackson Heights, Queens in the Sixties and Seventies. I don't remember knowing my garbage man. But there was the fruit man they used to come by. The guy sold eggs right out of the back of a station wagon, and there was an Italian guy, unless I'm crazy, I think I remember him coming down my block with a horse-drawn wagon of fruit.

JM: Wow!

TPF: And the milkman, I mean, those were the days.

EB: I remember a pushcart when the guy would shout out 'Strawberries!' and you would hear it in your home.

|

| Maintenance Artist poster |

AKT: Maybe we're getting back there a little bit. Farmers’ markets are booming.

TPF: That's true. That's true.

AKT: I think there's some hope. The Freshkills Park I want to add, because I liked her perception about the shopping center and the landfill in their “insane juxtaposition.” I think that’s how she calls it.

TPF: Exactly.

AKT: It is so truly insane, and so much encapsulates where we are.

TPF: You know, there's a piece missing from that, because it's actually not just the fact that there's a shopping mall and then a dump. A third pole of that configuration are oil tankers, and the oil companies who help create all this consumer stuff. Another partner in that triad of production, consumption, disposal.

JM: I love when she says people could just buy, consume everything and toss it over to the other side into the dump. It's a great moment.

EB: And it's World Oceans Week, too, right now, with the plastic in the oceans and all of that ties in with what you just said.

AKT: I currently have a summer course on fairy tales and storytelling at Hunter College.

TPF: Oh, how great!

AKT: There are lots of students with different cultural heritage and I ask each of them to present a folktale they grew up with. A popular Chinese one is that of the Monkey King, Sun Wukong. There are different versions about the origin story. In one of them the monkey gets a job as the imperial keeper of the Jade Emperor’s stables, and he's so proud about it. In another one he's taking care of the heavenly peach yard. In both versions of the story, he eventually finds out that his is the lowest position that is given.

|

| Tribeca Festival at Spring Studios Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

TPF: Oh!

AKT: This completely changes how he feels about himself. The wonderful job that he enjoyed so much, his happiness, switches. The lack of outside prestige changes everything about his perspective.

TPF: Wow, that's so interesting! I mean, think about the work Mierle does. Every artist when they're starting out wants glory and of course she wanted the glory, but she understood that there are people along the way who do very un-glorious jobs who are necessary, and she really tied her fate with them. Another feature of her work that meant so much to me was the fact that she's a public artist. There's so much going on in the realm of public art that we also don't really see, or if it's very splashy, you know it has to be a Richard Serra. Well, Tilted Arc didn't do so well. But the notion that there's somebody who was outside the marketplace and doing things not just with the public, but for the public, was a huge, huge source of inspiration for me.

JM: When she says the people that worked in the building never came up to see the exhibit, it's not something that's just for some people, like that's it. Some of the beautiful things about her work are that it's for everybody.

EB: And the exhibition at the Queen's Museum that you include with the mirrored sanitation truck!

TPF: It's beautiful. We had it at the première.

|

| Tribeca Festival |

AKT: Oh! In Tribeca?

JM: On Second Avenue outside the theater. It was amazing.

AKT: Mierle says: “I am like them almost, and a bit not,” which is beautiful syntax!

TPF: I noticed that over the years she bristles if anyone says, are you like a social worker? She's like, no, I'm not a social worker. I'm an artist. I think that's very, very important to her, that people understand that what she does is not social work. It is art, and to the extent that she wants to give freedom to these maintenance workers it's through the medium of art. It's not through the medium of social work.

EB: And you start at the very beginning with the dumbfounded looks on the workers. Are we being pranked?

TPF: They gave her a chance, you know. They gave her a chance.

JM: Watching this lone woman walk into this group of all men I always find so amazing. Just her.

TPF: It's fearless. I mean, it requires a degree of courage and fearlessness that she has.

EB: She has the presence for it.

|

| Robert De Niro and Jane Rosenthal at their Tribeca Festival Lisboa launch party Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

TPF: Right, and the passion. She's absolutely passionate.

AKT: And that can be used everywhere and anywhere. I even thought about how at Hunter College the elevators seem to break down nonstop. It’s a constant issue. Maybe there should be sponsors with a plaque, and it could be made into a maintenance artwork. I keep you informed if anything comes of it, and then it'll be a big thank you for Mierle! Well, thank you so much for this.

TPF: This was a wonderful interview, so thoughtful, and your reactions are really so spot on, and so insightful and very much appreciated!

AKT: I was convinced after the first few moments of your film.

TPF: Great! Great meeting you, too, Ed, really. Thank you.

JM: So nice to meet you!

EB: Let's stay in touch!

TPF: Yes, let’s!