|

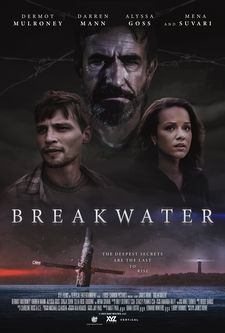

| Breakwater |

Director James Rowe returns to filmmaking with Breakwater, the type of genre picture he says he has been longing to make. His previous credits include the undergraduate short film, Sax Man, which was acquired by the Public Broadcasting Service, and his 1999 feature début, Blue Ridge Fall.

Passionate about teaching, he has continued writing. Breakwater resumes his interest in the theme of ill-fated choices. The story centres on Dovey (Darren Mann), a young, impressionable ex-con, and his prison mentor Ray Childress (Dermot Mulroney). Feeling indebted to the man who helped him survive his incarceration, Dovey breaks his parole conditions and crosses state lines to find Ray’s estranged daughter. Little does he know the murky past father and daughter share, that spirals out of control, leaving a trail of collateral damage.

|

| Breakwater |

In conversation with Eye For Film, Rowe discussed his phenomenal introduction to filmmaking, grounding action in character and place, and honouring what he owes the audience.

Paul Risker: I might ask whether there was a moment that ignited your interest in filmmaking, but your introduction to filmmaking came early when you found yourself on the set of a Michael Mann film.

James Rowe: […] There was something magical about that experience. I grew up in Asheville, North Carolina, where they shot The Last Of The Mohicans. When the movie came to town it was a big deal. I just knocked on the door and said 'I'd love to do something on this.' I didn't know much about the process of making a movie - I'd just started to learn how many people are involved, and a lot of people still don't understand how much it takes.

They let me work with the publicist Peter Hoss, driving the actors into backcountry picturesque locations to shoot the one sheets with Daniel Day Lewis, Madeleine Stowe and the other actors.

When Peter went back to New York, I wanted to stay on and learn more. I had long hair at the time, I was in a band, and so the assistant director Michael Waxman said, "Why don't we just bring you on as a trained extra. We'll put your hair back in one of those queues”, (the ponytail that the British soldiers had). I trained with Dale Dye, the military advisor who trained the guys in Saving Private Ryan, Platoon and a bunch of other great movies. We went all out, in full regalia, the uniforms and the brown bess rifles for two weeks of training.

As you probably know, much of the time is downtime when you're making a film. I got to sit there in my uniform and watch Michael Mann, Dante Spinotti, the Italian cinematographer, and Daniel Day Lewis and Madeleine Stowe work. It was a phenomenal intro into the workings of a film set and the business.

PR: I often wonder whether the popular image of film directors, from Jekyll to Hyde like personalities in their obsessive pursuits, is a type of dramatised lore. To have seen Michael Mann at work must have been an eye-opening experience.

|

| Breakwater |

JR; First of all let me tell you a story about who I thought Michael Mann was when I first started working on the film. I thought that Michael Waxman, the assistant director was Michael Mann. Everyone was calling him Michael and he was the most boisterous person on set. He seemed to be in control of everything, as the assistant director should be. Michael Mann ended up being the quiet guy, always off to the side with the actors. As I remember, he never spoke to everyone as a whole, and that could potentially be because of the way Daniel Day-Lewis works. He’s a very focused and quiet actor, until he's not. There's a lot of gravity in that approach.

That was me being a bit naïve and thinking the director must be the guy yelling at everybody to hurry up. The best directors certainly aren’t that. Often times you don't hear the director if everything is going well because they're having conversations with the cinematographer and the actors. These are quiet conversations, adjustments they're making off to the side. It doesn't mesh with what you think of as, I don't know, John Ford or someone on a big crane with a megaphone yelling at hundreds of people to get the horses moving in the right direction. I'm sure that happens too.

[…] From my standpoint as a director, if you're working in a calm and focused way, then everybody is moving forward and thinking about it beforehand, rather than rushing. I like to maintain that level of calm on the set, until of course things go crazy, and on independent films things often go crazy quickly.

PR: Breakwater could be described as a return to your roots, but how do you perceive the dichotomy of filmmaking and teaching for you personally?

JR; I went to film school and then the AFI (American Film Institute). I appreciated my time there, but I already had a movie in the works when I went to the AFI. I was pretty young, and I'd already made a short film on my undergraduate programme that was bought by PBS. So, I felt I knew what I was doing early on, but I got a lot out of talking to professionals I met at the AFI.

|

| Breakwater |

There are many professionals and great filmmakers I've met inside and outside of the classroom, but in the classroom they're not always great teachers because they maybe work instinctually. They've learned their methods and processes, but they've a hard time analysing these and sharing them as a set of tools with a group of students. Then, there's that old saying, “If you can't do, you teach.” I know there are some teachers who can't make very good films or can't make a film at all.

I was fortunate enough to have made a number of short films and then a feature film before I started teaching. The only reason I started teaching was I was living in LA, but I was back in North Carolina for a summer. I put together a little class at the community college to talk about screenwriting and my process. It was called, Words In Motion and I enjoyed that experience.

Wherever I went after that, even though I was still writing (a pilot that Starz was going to make, and a movie that was made by another director), I always tried to find a place to teach. I taught at the University of Colorado, Denver, the Colorado Film School, the New York Film Academy, and I've even taught overseas.

When you're thinking about filmmaking every day and talking about the different ways to approach the process with students, then you're learning. It has shaped my ability to make films and coming back to filmmaking with Breakwater, after all these years of teaching and watching movies, there are things I did on this movie that I never would have known to try on my first film.

PR: If Breakwater wasn't a singular or obsessive idea that drew you back to filmmaking, what was it about the story that compelled you to tell it?

JR; It wasn't a question of it being ten years in the making, but it takes me a while if I get hooked into the idea of a place. Breakwater is set on the outer banks of North Carolina, which I'd visited five or six years ago. I'd always had an affinity for the place. Especially in the offseason, I find it to be windswept and mysterious, and a bit lonely. I love it up there; it's beautiful.

|

| Breakwater |

I visited the Currituck Beach Lighthouse. It's different to other lighthouses I've been to because it’s not out on a rocky point, it's surrounded by trees. For a lighthouse, it seemed like it was hiding itself. I thought it was a great character location and I just needed to figure out why someone would come here? What would they be hiding that would play with the idea of the lighthouse shining a light on, and what is hidden coming to the surface?

Sometimes I build from a place, sometimes a character, and sometimes it's a situation. This isn't the movie I've been waiting to make for 20 years, but I have been waiting to make this kind of movie for a long time. It has taken five to six years since the first inkling of an idea. I put everything into this. It starts in a prison, it goes across two states, and it's set on the water, even underwater, and in a lighthouse. I wanted to challenge myself with the action set pieces, but keep it grounded in place and character.

PR: The story is anchored by characters, all of whom have a past, alongside sharply written dialogue that leads to engaging scenes. It leads me to think about how the formulaic story has to continually renew the audience’s interest, energising the familiar narrative.

JR; Some of my favourite scenes in the movie are quiet. I love the scene some 25 minutes in, when Luis (Daniel Williams-Lopez), a young man we haven't met in the story yet, comes to visit Ray. They talk through the cuff port in the prison cell door. There's a lot thematically going on there.

Those scenes put something in the back of the audience's mind that they’ll hold there, knowing it means something. You can play with that little thing you've planted. If you plant it in a character driven way, then it feels like two guys having a conversation, but it's a plot point, only it’s not an obvious plot point at that moment. I think that's close to what you're saying.

|

| Breakwater poster |

Breakwater is a genre film and some of the greatest movies of the Seventies, Eighties and Nineties were genre movies. The Godfather is, and so I just wanted to do something that was a little more literary. It's going to have the genre beats in it like you said, and when you say formulaic, I'm assuming you mean structurally there's things in genre we count on are going to happen. It's a question of how they unfold and whether we care.

All of these characters have pasts that they're trying to outrun, and their pasts are not done with them yet. So, these characters are converging upon each other, but their pasts are close behind, and they're driving a lot of their choices.

I always attempt to marry a more literary approach to character with a genre, and if you’re able to, even if something feels expected, the way we got there wasn't, and the journey felt like it was earned. In Breakwater it feels earned at the end because of the characters’ choices and what we come to know about them.

PR: The ending you choose interests me because just as the characters’ choices deny them, you effectively complement the themes of the film by denying your audience closure, leaving it to us to imagine what happens next.

JR; What you owe the audience is an imagined future and they get to create that. The end is the end right! The Shawshank Redemption ends with Andy Dufresne and Red reuniting in a wide shot on Zihuatanejo beach. There's something very satisfying about that for a lot of people. I would have been fine if I'd just seen Red start his life again, with the notion that he would one day reunite with Andy.

In Breakwater, Dovey finding the note that had been left for him has the western aesthetic of the cowboy who rides off into the sunset. I wanted a little bit more of that notion that Dovey is on the boat with his father, where he belongs for now. They're motoring off into the sunrise and yet we realise maybe Dovey’s story doesn't end there with his father. We get to create that imagined future for him.

Breakwater is released theatrically in the US on Friday 22 December 2023, with a VOD release to follow.