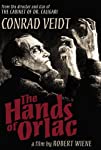

Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Hands Of Orlac (1924) Film Review

The Hands Of Orlac

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

The world’s first successful transplant surgery was carried out in 1905, when Dr Eduard Zirm grafted a donor cornea onto the eye of an injured workman in Olmutz, Moravia. The lucky recipient not only came through the operation without complications but retained his restored sight for the rest of his life. Despite this, however, the idea of transplant surgery was something that many people found deeply disturbing. This wasn’t simply a fear of side effects, or squeamishness, as it often is today. It was connected to widespread belief in an unalienable connection between body and soul. Out of that fear came Maurice Renard’s sensational 1920 novel, Les Mains D’Orlac, and out of that novel came this, one of the most impressive horror films of the silent era.

Like Renard’s book, it opens with train crash. Today, of course, we would probably see the impact, but we wouldn’t feel it like this. We travel there with Yvonne (Alexandra Solina), wife of the famous pianist Paul Orlac (Conrad Veidt), and share her sense of disorientation as she searches through the wreckage for the husband she was scheduled to meet. The vast set is lit by swinging arc lamps and torches, their glow diffused through plumes of smoke. Rescue workers rush around with stretchers. The scene is vast, chaotic; Yvonne is a tiny figure but a determined one. When she finds Paul alive, her relief, too, is palpable. In the hospital, however, it emerges that his injuries are severe. Alert to what his music means to him, she begs the doctor to save his hands, and the doctor responds by replacing them with all he has available – the hands of a man called Vasseur, recently executed for murder.

Can a pair of hands possess murderous intent? The doctor says not, but Paul is horrified when he learns what has happened, convinced that the spirit of the dead man is somehow urging him to do terrible things. There’s a great bit of special effects work introducing this concept but it’s Veidt who sells it to use – without sound, of course, though there are an awful lot of intertitles to help us handle what was at the time a fairly complex plot. When Paul finds a knife at home and becomes certain that it belonged to Vasseur, he fears that he is on the verge of doing something terrible – perhaps even to his beloved Yvonne. Complicating the situation is that fact that his new hands seem unable to play the piano, so the couple are forced into debt – making the prospect of paying for future surgery to undo the transplant seem hopeless.

In 1924, even the concept of shell shock was new and poorly understood, yet Veidt’s take on Paul now looks very much like an interpretation of post traumatic stress disorder, something he might have witnessed in those he served alongside in Warsaw during World War One. His depiction of somatoparaphrenia (‘alien hand syndrome’) is also intriguing; it’s worth noting here that Paul suffered head injuries as well as losing his hands. Is his obsession the result of a psychiatric disorder or a real supernatural force? If the former, could it still be dangerous? In many ways, Paul’s experiences reflect those of the war veterans of the period, as he struggles with the awareness that he has the potential to harm those around him. As he contemplates taking drastic action to reduce this threat, however, further plot developments give him a new crisis to contend with.

We’re a long way here from The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari, which also starred Veidt, but the legacy of German Expressionist cinema is present in some of the exterior scenes, seeming to speak to Paul’s mental state. The interiors are fairly plain, simple stages allowing the actors to pull us into their inner worlds, but everything is beautifully photographed. High ceilings and streets lined with tall buildings emphasise their smallness, reflecting their vulnerability in situation over which they have little control. Through this, the film explores attitudes to technological progress and the social upheaval which followed the war.

Probably because of its sensational theme, The Hands Of Orlac has never really got its due from critics, despite a positive reception in Austria on release. The remakes it has inspired and other films it has influenced have not reflected its best qualities, but it’s a more sophisticated film than its central concept suggests, and there’s a good deal about it that is worthy of admiration. Veidt is superb. It’s not his best film but this is one of his best performances and anyone with a passion for silent film should make sure to see it.

Reviewed on: 05 Nov 2021