Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Haka Party Incident (2024) Film Review

The Haka Party Incident

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

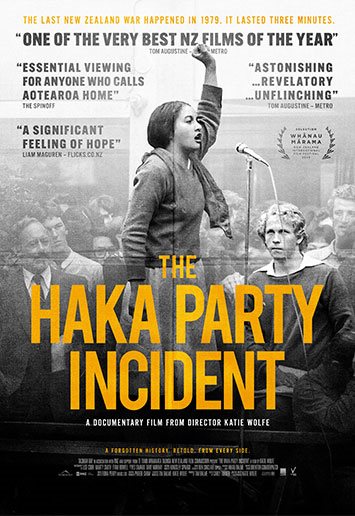

On the 1st of May 1979, in Auckland, New Zealand/Aotearoa, a group of Māori activists clashed with a group of engineering students who were engaging in their annual drunken ‘haka party’ and parade. In Katie Wolfe’s documentary, which screened as part of ImagineNative 2025, one of the students recalls that it wasn’t until the incident got to court that he realised it was about something much bigger. It would emerge as a pivotal moment in the history of the Māori struggle for equality. This film looks into the circumstances of the clash itself, speaking to a number of participants from each side.

They’re all older and wiser now. That distance has made it possible for them to look critically at their actions, though there is also a measure of respect here for the impulsivity of youth, without which change that they can all now see was needed might not have happened. Although the film opens with black and white images of the partying students which many viewers will immediately perceive as shockingly racist, Wolfe then carefully establishes the wider social context which meant that the students themselves might not have done so. They don’t try to make excuses for themselves but acknowledge that, at the time, they were not deep thinkers. Some deeply uncomfortable clips from popular TV shows (which, one should note, did have similarly ugly equivalents elsewhere in the world) show Māori people represented as comedy figures, their traditional dress mocked, the haka itself mimicked in ludicrous ways to make it look pathetic, to encourage white people to laugh at the ‘savages’.

If you’re not familiar with the concept of a haka, it is best described as a type of dance or performance art used to convey respect or celebration. Haka are used to welcome guests or to show admiration for a life well lived at a funeral, and so forth. They’re probably best known around the world due to their use by the country’s rugby team, the All Blacks, though that has led to the erroneous impression that they are always about challenge. In November 2024, Te Pāti Māori MP Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke performed one in parliament as part of a protest against a controversial bill, making waves around the world. In sum, they are a serious form of expression, varied according to origin and purpose but formally structured. They are not about a group of skinny white teenagers with offensive slogans painted on their bodies donning grass skirts and leaping around at random with their tongues sticking out.

Students, of course, need opportunities to let off steam, and aside from the racism their drunken antics seem to have been light-hearted and not so different from those one might encounter anywhere else in the world. They were, as the documentary makes clear, poorly policed, with class privilege as well as white privilege allowing participants to take their behaviour too far on a number of occasions, sexually harassing women and destroying property, but the key distinguishing factor was the ridicule they heaped upon an already disadvantaged, minoritised group, and the way that privilege had allowed their participants to grow up without ever questioning such behaviour or reflecting on the way it might feel to those people. This meant that when the clash happened, they were completely unprepared.

The Māori group, He Taua, though they were a similar age, were a lot less sheltered. They insist that they didn’t plan on violence, but one also observes that, depending on where one socialised, what happened might not really be considered violent. At any rate, no-one was seriously hurt – at least not until the police got involved. No documentary evidence is supplied to back up accounts of police beatings, but given the frequency with which such stories emerge wherever power structures like this exist, they don’t stretch credulity. The important thing was that the pretence that behavior like the student ‘haka’ didn’t upset anybody was well and truly shattered. As the incident made news headlines across the country, white society was forced to recognise that Māori people were real and present in society, had feelings, and could no longer be relied upon to be submissive.

For the bulk of the film, Wolfe keeps the Māori and former student contributors apart, creating space for the sort of self-reflection that might have been suppressed if residual tensions – or just embarrassment – emerged when they were together. Moving back and forth between these groups allows the narrative to evolve in a way that takes different perspectives into account without setting them against one another. This is particularly useful in revealing the dynamics of systemic racism and its ability to make even well-intentioned people into agents of harm. It lets the white participants explore what their responsibilities should be within such a system, and how to actualise them.

When the two groups do come together, in the final scenes of the film, the focus is very much on togetherness and on the assertion of a new way of being from those islands. It’s an explicitly anti-racist message in which Māori power is restored and white people, too, make direct gains from their willingness to listen, to concede.

Reviewed on: 08 Jun 2025