Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Devil's Bride (1974) Film Review

The Devil's Bride

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Back when the Soviet Union was in its prime, it was commonplace, in the West, to mock its citizens for their ignorance of Western popular culture: fashion, music, film, and so forth. it’s true that many trends were slow to arrive there, but that gave Soviet artists something of an advantage, because it meant they were able to examine them at a distance, to strip out what was valuable before becoming overwhelmed, and thus to work with them in new and different ways. Arunas Zebriunas’ 1974 take on Lithuanian myth, The Devil’s Bride, is a rock opera made with full orchestral support which combines an assortment of cultural and countercultural motifs from the previous decade to create something altogether unique.

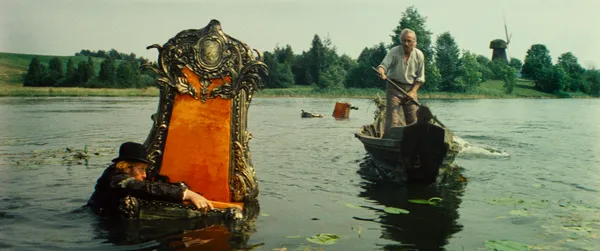

Recently restored by the Lithuanian Film Centre and screened as part of Fantasia 2025, The Devil’s Bride is in remarkable condition for a film of its age, with vivid colours and a crisp soundtrack. it opens high in the mountains – in Heaven – with God Himself sitting on a velveteen throne as His angels gather for a banquet. As He dozes, however, they are seized by temptation, and begin to cavort and dance on the table to Vyacheslav Ganelin’s funky jazz score, appearing as men in sharp black suits and bowler hats, with women in bright orange dresses. Sharp eyed viewers might spot, in the midst of this, a groundbreaking same sex kiss, which slipped past the censor because the scene is, after all, depicting sin, but which might be interpreted more positively in the context of everyone obviously having a good time. When God wakes up, however, there is trouble. The devils are cast out of His kingdom – the throne, curiously, falling along with them.

It is the presence of this incongruous piece of furniture that first catches the eye of windmill owner Baltaragis, who is out in his boat for a spot of fishing. He’s very pleased to bring home a devil in his net instead, and puts the unfortunate creature (one Pinčiukas, played by the young Gediminas Girvainis) to work as his slave. Pinčiukas, however, is a crafty fellow. Sitting in the window, stroking his pointy red beard, he sees how Baltaragis looks longingly at Marcelé, a Sixties-style beautiful blonde whose whole existence seems to consist of drifting up and down the river wearing a long white dress and singing romantic melodies. A deal is struck. The devil will arrange for Baltaragis to marry Marcelé on condition that their firstborn child will belong to him.

Deals with devils are always tricky things. Suffice to say that Baltaragis gets what he wants, but only briefly, and spends most of the ensuing years in sorrow. We pick up the story again when his daughter Jurga – played by the same actress – comes of age. Now Pinčiukas is ready to claim his prize. Nothing is quite that simple, however. First there is the matter of the mill owner’s scheme to trick the devil into marrying his sister Uršul instead. She’s a woman who doesn’t put up with bad behaviour from any man, regardless of his pedigree. And then there’s the arrival on the scene of a fur-clad stranger, the rogueish Girdvainis, whose falls for Jurga at first sight and plans to make her his own.

Like Milton's, Zebrunias’ devil is cast in semi-heroic mode, a comic character against whom events continually seem to conspire. A witty script by the poet Sigitas Geda sees him making much of his misfortune, and towards the end we see him glancing skyward as if longing to be restored to his celestial home, but horror fans in the audience will be pleased to hear that what we get instead is a proper torch and pitchfork-wielding mob, whose own monstrous nature is clear to behold. The final scene, like the first, is captured as a painting in a gilded plaster frame, reestablishing the position of the story as a mythic take on times gone by. It’s a cute gimmick which suits this playful, raucous but gorgeously constructed piece of work.

Reviewed on: 07 Aug 2025