Eye For Film >> Movies >> Skinamarink (2022) Film Review

There’s a quality to old, worn Super-8 tape which recalls the experience of staring at a ceiling in a very dim but not quite pitch dark room. Aware that there’s something there yet unable to identify it properly, the eyes continually focus and refocus, creating a dance of swirling colours and tiny patterns which appear and disappear as the brain tries to pick out definite shapes. The experience of watching Kyle Edward Ball’s astonishing début film is similar. It’s not just the immediate effect on the eyes, which persists throughout. It’s that right from the start one has the uncanny sensation that there’s something there which one can’t quite see.

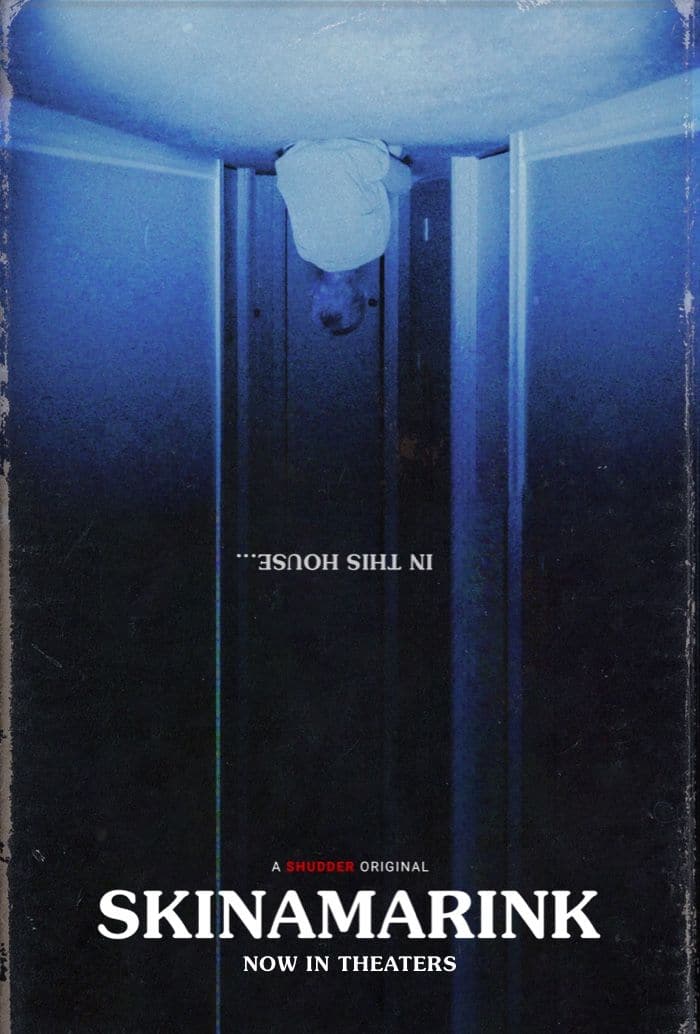

The effect is hypnotic, strangely calming in the early scenes, when Ball intermittently switches colour palettes in a way which looks organic but tricks the brain into paying more attention and plays with its sense of rhythm. It is late at night. The children are supposed to be in bed. We see bits of the house from odd angles: the corners of the ceilings, lights, power outlets, the textures of carpet, the round knob at the top of the banister, panelled doors which have been painted over and over again with gloss and never stripped and properly finished. Discarded lego stands out brightly. There are also cars, a small bear, a velvety snake with a pointed felt tongue, and those less certain bits of bric a brac which children acquire and turn into toys. After a time, we hear a phone number being dialled (if you pay attention, you can catch the ‘555’). The person making the call, unseen but with a masculine voice, says that Kevin fell down the stairs and hit his head, but he’s fine and they didn’t even need to do stitches.

It’s a rare fragment of dialogue in a film whose audio aspect is comprised mostly of differently textured silences. It’s also a rare indication of the presence of an adult. Pretty soon the only people awake are four-year-old Kevin and his sister Kaylee. We don’t learn her age, but she’s very young. Something is wrong, but they don’t seem to be able to get Daddy’s attention. They wonder why Mommy is crying. They do what kids do, dragging bedcovers downstairs so they can snuggle up together and watch Felix The Cat cartoons on TV. A reassuring melange of old kids’ TV themes accompanies the flickering light, but the children’s efforts to be practical only make it clear how wrong things are. They are curious where adults would be terrified. Touching a smooth wall, Kevin asks absently “Where did it go?” He’s referring to a window.

With only the children to help them comprehend the situation, older viewers might easily become frustrated, but somehow Ball evades that danger, providing just enough clues to keep deepening the mystery and making it ever more uncanny. In a single shot, he rips away the illusion we’re likely to have bought into with regard to our perspective. There are shades of the James Tiptree Jr short story I’m Too Big But I Love To Play, and you may find yourself wondering about those cartoons and how they might be interpreted by something with a different frame of reference. In one, Felix watches a rabbit as it places a hat on its head and disappears, over and over again.

Skinnamarink is an old song, a remnant of a now forgotten comedy play from 1910. It isn’t played here, though you might give yourself a further shudder by listening to it afterwards. There is also Skinny Malinky, a character in a Scottish rhyme, who went to the cinema but couldn’t find a seat. No other cultural reference comes to mind, and no explanation of the title is ever given, but it seems to have a Rumpelstiltskin-like quality, that suggestion that to know the name of a thing offers some kind of power, some means of understanding it. In the dark, in the swirl of static, you will find yourself reaching for such scraps of knowledge, folklore seeming no less applicable than science, but even if you think you might achieve understanding, it’s all too clear that a four-year-old cannot. If you are a parent, you will feel a clawing urge to grab the children and pull them out of there. For other viewers, the fear will be purely personal. In any case, it doesn’t let go.

Films like this come along once in a generation. Skinamarink is something wholly distinct, consuming in its otherness, the warm, nostalgic quality of the home it depicts serving only as a trap. Of all the films at this year’s Fantasia, it is the hardest to forget – and late at night, when you are lying in almost total darkness with your eyes open, you will try.

Reviewed on: 28 Jul 2022