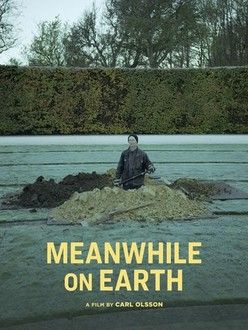

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Meanwhile On Earth (2024) Film Review

Meanwhile On Earth

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

It’s difficult to process grief in the absence of a body – there is always that tiny little bit of the brain that clings on to hope, arguing that one’s loved one may still be alive. When the disappearance happened in space, however, there is no real rational way to justify such thinking. Captain Franck Martens (voiced by Sébastien Pouderoux) was a local hero. There’s a statue of him on the roundabout, visible whenever one drives in or out of town. His sister, Elsa (Megan Northam), who passes the statue every day on her way to and from work, has no opportunity to put him out of her mind, no chance to heal.

Under the pressure of that kind of grief, the mind can do strange things. Elsa is 23, so right in the age bracket where schizophrenia is most likely to manifest for the first time. When, late one night, she starts hearing her brother’s voice in her head, one might naturally wonder if that’s what’s going on – and indeed, writer/director Jérémy Clapin teases it as a possibility throughout – but as an assistant to people facing cognitive decline, one would think that Elsa would herself be alert to this. In the end, it might not really matter. The film is less concerned with the external world than with her trauma and the decisions she must make as she tries to find an ethical solution to the situation in which she finds herself.

One might, alternatively, read this as science fiction or as a sort of folklore. It’s a glowing seed that gives Elsa the ability to tune in clearly to the voices, and then makes it impossible for her to tune out. When she follows their lead (someone else does most of the talking, Franck having been ‘deactivated’ because ‘it uses less oxygen’), she finds herself deep in the woods. To get her brother back, if it’s really him, she is required to make a sacrifice. Can she do it? Can she trust the promises of a conversation partner who admits to wanting her help to bring five otherworldly buildings into our world?

Sometimes grief is so intense that one becomes wholly obsessed by its object and it’s impossible to recognise the humanity of anyone else. Elsa is capable of understanding that intellectually, but her emotions are hard to control. What’s more, as the story develops, one gets the impression that she’s afraid of controlling them. Letting go of her obsession would mean letting go of much of what remains of Franck.

Clapin is best know internationally as the director of 2020 Best Animated Feature Oscar nominee I Lost My Body, and admirers of that film will be pleased to learn that there are animated sequences here. Elsa is constantly sketching people and her childhood fantasies are captured in scenes where she and her brother adventure together, suggesting that these things are linked. in several places – most notably the tunnel sequences towards the end – the film makes reference to Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris. Who is dreaming who?

There’s a sweet, melancholy flavour to Clapin’s work, despite the occasional inadvertent bit of humour – the English subtitles have presumably been created without much human involvement, as in a scene when Elsa calls out her brother’s name it appears as ‘F**k’. There are also moments when it will send a chill right through you.

Reviewed on: 26 Aug 2025