Eye For Film >> Movies >> Holding Liat (2025) Film Review

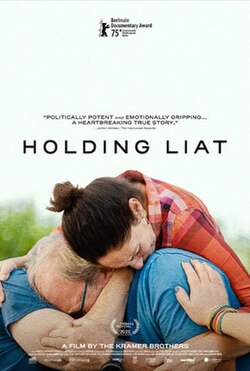

Holding Liat

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

On 7 October 2023, a series of attacks on Israel by Hamas operatives and their allies lead to the deaths of 1,195 people. 47 of these died a Nir Oz kibbutz near Nirim, and 76 were taken hostage. After intensive lobbying by their families and assorted diplomats, the majority of these have now been released – and yet, over 62,000 Palestinian deaths later, the wider world has still heard relatively little from them and their families, their voices drowned out by those purporting to act on their behalf. Now, in Brandon Kramer’s award-winning documentary, the story of one of them is told.

Liat Beinin Atzili, a schoolteacher who specialised in Holocaust studies, was 49 when she was taken along with her artist husband Aviv Atzili. Their three grown children were all at the kibbutz but got away unharmed. For many months afterwards, the family had no idea whether Liat and Aviv were alive or dead. Two weeks after the attack, Kramer, a distant relative, stepped in to follow Liat’s parents, Chaya and Yehuda, as they struggled to get information and to make sure that every effort was bring made to secure their loved ones’ release. The film opens with a moment that sees sorrow mixed with relief as Yehuda gets a phone call to confirm that Liat is alive and a prisoner. There is no information of Aviv.

What follows is an agony of waiting. The two parents handle it differently. They’re originally from New Jersey, so Yehuda gets on a plane and goes to talk to US politicians, certain that they are more likely to mount a successful intervention than anybody working for the Israeli regime. Chaya remains at home in Shomrot kibbutz, close to her grandchildren, doing embroidery, coping in her own quiet way. When they’re together, the couple get on one another’s nerves, eventually descending into an on-camera argument. Small stress fractures in their relationship and magnified by their mutual distress.

We meet other family members. Netta, the youngest of Liat’s children, is traumatised by his experience, having thought that he was going to die, and expresses anger at all Palestinians, which his grandfather gently tries to talk him out of. Liat’s uncle, by contrast, said that he felt as early as 1972 that he was living on stolen land, and that was one of the reasons why he left. Liat has a sister who did likewise simply because she couldn’t see a realistic way for the conflict to end and, she says, it was all too much. Netta’s older brother, Ofri, expresses only pain, but strives to be useful by tending to the gardens of the kibbutz, taking over from those who are missing, freeing up time for others to act.

Yehuda sums up his own position bluntly. “Here there are events over which we have no control, and we’re being led by crazy people, whether on the Palestinian side or the Israeli side.” He’s angry at the naivety of pro-Zionist propaganda in the US, and the way that he sees people in his position being used for political ends; angry, too, that no-one is talking about the 7,000 prisoners Israel is holding. Without honesty and real engagement, what hope can there be? At one point he meets a Palestinian advocate and they quietly converse, straying beyond their official remits, discovering that they have many opinions in common because they both want to prioritise peace and save lives.

There are visits to Nir Oz. In an obscure corner of a wall, brown streaks mark the place where blood splattered from a wound, but one would not notice them if one did not look. The place looks messy but innocent. Given the local pressure for living space, one wonders how long it will remain a shrine – but it’s hard to anticipate the future here, no matter how one might try. Clips from Liat and Aviv’s wedding video shows us a sea of happy faces. Liat’s sister says that in the past she wasn’t really thinking about what life was like for the people on the other side of the wall.

Although her absence fills up the lives of those who love her, Liat will eventually return, filling in gaps with her presence and her words, confounding many imagined versions of what might have happened to her. Her experience is, of course, only that of an individual, and cannot represent what happened to all of the other hostages, but it still has significance. Nothing will be the same for her now, not only because of her suffering, but because she has seen what it’s like on the other side, and people there have seen her, up close, and they have talked. Plainly, without fuss, and in defiance of all the horrors of the present moment, Holding Liat opens up space for a larger conversation.

Reviewed on: 12 Sep 2025