Eye For Film >> Movies >> Encounters (2023) Film Review

Encounters

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

If there’s one thing that can be said for the Soviet project, it produced some damn fine science fiction. There’s nothing like living in a grim present which continually promises a great future to inspire new visions of the way that humans or others might exist, and nothing like restrictions on criticising one’s government to precipitate the development of parables. What’s interesting is how well that tradition has survived to the present day, blooming again as Putin has tightened the screws. Dmitriy Moiseev’s Encounters acknowledges its roots with direct reference to forebears including Tarkovsky’s Solaris, but also in its style and, dare one say it, its quality.

The Soviet legacy is everywhere present in the remote Russian town where the action in this film takes place. Crumbling apartment blocks line the streets, which are largely empty of both traffic and pedestrians. Older buildings and the remnants of factories lie in ruins. There is mud everywhere; we see it frequently in close-up. Like the bare branches of trees, the perpetual damp, the stain of encroaching lichens, it suggests that nature is attempting to reclaim what humans have failed to care for, but that nature itself shares that sickness of the soul that led to this collapse. Old women with bowed heads shuffle past statues of ambitious men holding hammers and sickles, gazing up at symbolic stars. The real stars, now, are only another source of fear. Who knows when a second wave of invaders might emerge from them?

The first wave came in the Eighties. Clips of old news footage fill us in. It wasn’t much of an invasion, it seems – indeed, that characterisation might itself be a matter of political convenience. The T-men were quickly subdued and secreted away by the regime, kept in remote bases where they could be subject to experiments. Meanwhile, cutesy versions of them appeared as characters on kids’ TV. We see a group of children dressing up as them and performing a dance. Random members of the public share their thoughts on the arrival of the spaceships. In a news segment, Boris Yeltsin stands next to one of them, smiling and laughing, clearly a few drinks in already.

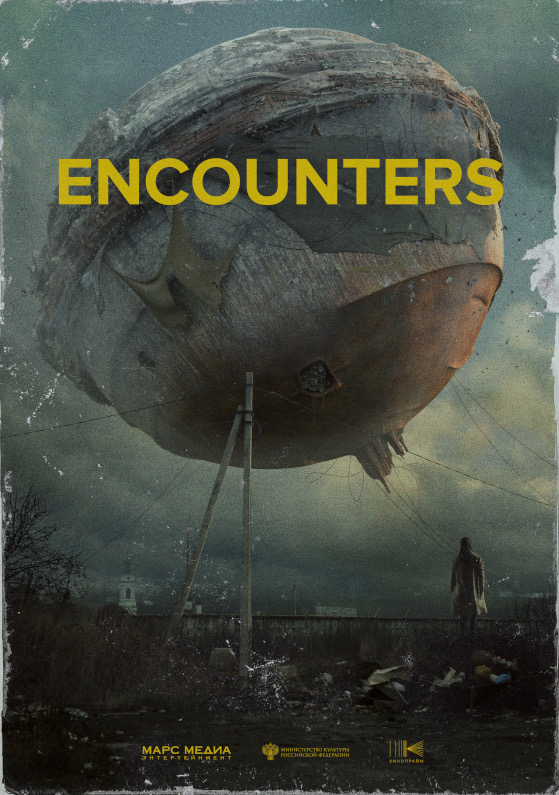

The spaceships required too much force to move for the government to consider it to be worthwhile, so now they remain where they first descended, hovering a few feet above the ground, slowly rusting away. In the opening scene, we see a boy throwing stones at one of them, watching as they’re caught and hover in its gravitational field. The boy is part of a loose community living in this neglected place. We will spend most of the film with Nina (Irina Salikova), a local nurse who has been stuck there due to her father’s illness, but whose life is about to change in a way she never predicted.

Real change necessitates a change of perspective. That’s what totalitarian regimes are always most afraid of – and yet it’s also something they need if they are to make technological progress, necessitating a careful approach to science which involves constantly switching people between roles and making sure that as few people as possible can see the big picture – if in fact anything meaningful can be discerned in this way at all. Nina’s job is fairly basic. She is to take care of a creature known as Vitaliy who is in a weakened condition and needs to be restored to health so that a valuable substance can be extracted from his body, drop by drop.

The precise origin of Vitaliy is a mystery in itself, with hints of alien/human hybridisation or infection (again, as much about the infiltration of outsider ideas as body horror). Nina tries to be practical, to do her job as instructed despite her qualms, but she also has a secret agenda. The said substance, surrounded as it is by state secrecy, is worth a small fortune on the street. Stealing just a small amount could help to transform her father’s situation. Of course, he’d be horrified by the idea of her having anything to do with the aliens, and getting caught doesn’t bear thinking about. But then there’s the complication of Vitaliy himself.

The creature design here is magnificent, standing out even in the context of Fantaspoa. Soft and swollen-looking, loose-limbed, bruised and nervous, Vitaliy looks not only biological but genuinely other, and yet also relatable. It might be a mistake to think that one can read his emotions, and yet it’s easy to become fascinated by his behaviours, by the way the multiple opposable digits on his hands grasp a plastic carrier bag, apparently fascinated by its texture; the way the irises of his round, high-mounted eyes close and unclose as he peers at objects around him.

When Nina sleeps in his enclosure or sits quietly with him, singing him songs, he watches her, and we see her through his eyes: the different parts of her that seem important to him, the fascinating pores of her skin, the patterns of hairs in her eyebrows and the front of her scalp, the way her limbs fold. It’s a simple way for Moiseev to establish that Vitaliy doesn’t think like us at all – even after so long on Earth, he’s using completely different frames of reference.

The action is broken up with other pieces of information: more ‘archival’ clips, and snippets from scientific papers full of theorising about the aliens, their origins, their intentions, the possible dangers they represent, their biochemistry. Outside the facility, fixers and clients exchange little vials of the substance. They say it tastes like apple cider vinegar. Inside, we see Vitaliy hooked up to a pump, not resisting, long past the point at which he might have fought or even pleaded. In his company, Nina begins to change. Is it something biological? Is it simply that she’s acquiring an empathy which communism and capitalism, in their turn, had stamped out of her? Some viewers might think of the connection between Elliot and E.T. - The Extra-Terrestrial, but in context, this has a very different flavour.

With its use of extreme close-ups and focus on odd details, its heavy investment in atmosphere and its absurdist asides, Encounters is a visually hypnotising film, engaged in its own experiments with shifting perspective. It’s philosophical, curious, and not terribly hopeful, but it finds refuge from assorted tyrannies in the connections between individuals. If you find yourself feeling down after watching it, never fear: a selection of cat pictures just before the credits is there to cheer you up. Anyone who remembers Russia at the end of the Soviet era will find some familiarity in these, but they also speak a universal language. No matter what they have borne witness to, almost anybody can be persuaded to look the other way.

Reviewed on: 28 Apr 2024