Eye For Film >> Movies >> Darling (1965) Film Review

Darling

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

There is a point in John Schlesinger’s swinging Sixties hit Darling when Diana, played with Oscar-winning intensity by Julie Christie, is asked why, as someone who is presented as the face of modernity, she dresses so conservatively. Herein lies the crux of the film.

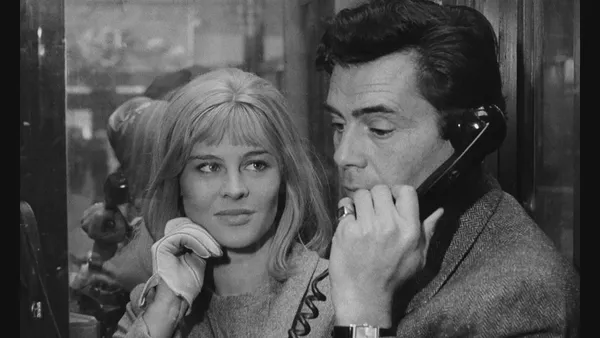

Diana is a model, the Honey-glo Girl, the Happiness Girl. She’s known for her dazzling, carefree smile, and the myth of her picture perfect life is so strong that she almost believes it herself. As much an artefact of consumer capitalism as the products she represents, she is desired in the same way, and she knows it. Her relationship with respected literary journalist Robert (Dirk Bogarde) – for which he leaves his wife and children – suits them both: she is the dazzling jewel on his arm whilst he gives her the intellectual credential she has craved. Behind the scenes, however, their unmarried bliss is gradually eroded by mutual jealousy, her unwillingness to make any real intellectual effort, and the deeper frustration that comes from her own desire to engage actively with the values of consumer society.

Now enjoying its 60th anniversary with a beautifully restored print, Darling may suffer from aspects of its social critique having aged out of relevance, but in other regards it could not be more timely. Diana is what contemporary politicians would call a striver. Her association with progressive values is strictly superficial. She plays by the rules, always focused on her career, on her social status, and on getting close to the people who can help her advance. She uses sex, and sometimes seems to desire it for its own sake, but doesn’t enjoy it much (perhaps due in part to the widespread male ignorance about women’s bodies at that time). She lives in the heart of London, she’s seen in all the right places, and she carves out a fairytale life for herself, but no matter how hard she tries, the promise that this will bring her satisfaction is never realised.

The flm is packed full of the big social issues of the time: extramarital sex; divorce; abortion; gay, bisexual and gender-nonconforming characters (some of whom were edited out by the censors for its initial release); and, though it’s addressed only in passing, feminism. It’s not subtle with its criticism of the aristocracy and the nouveaux riches, though the most in-your-face of its satirical scenes is redeemed somewhat by Schlesinger’s deft directing of extras. People of colour are conspicuous by their absence except when they are expressly being objectified, and on a brief sojourn to Paris, where our heroine exhibits a twitchy discomfort. We often get the sense that she is repulsed by aspects of the world around her, but she is a consummate performer, always giving the public what it wants. Behind closed doors, she torments herself and those close to her with bursts of fury and a childish desire to ensure that whenever she feels miserable, it is shared.

In this regard, it is precisely Diana’s lack of intellectual sophistication that makes her interesting. She’s intelligent – quick witted, at least – but unable to process her own dissatisfaction, or unwilling to step away from comfortable assumptions in order to do so. Her self-destruction echoes a much more widespread social malaise. Self-assured magazine-style narration inadvertently highlights the lessons she’s failing to learn, yet though she’s often unlikeable, it is in retrospect increasingly difficult to see her as fully responsible for her fate.

Bogarde brings humanity to what could have been a pathetic or unpleasant supporting role, though it’s clear early on that Robert is out of his depth – and that he will struggle to remain useful to Diana. As Miles, the other major male influence in her life, Laurence Harvey delivers a more complex performance, suggestive of a deeper understanding of what’s going on. Though Miles clearly enjoys Diana, showing her off like an exotic pet, little that she does surprises him, even as he refuses to surrender to the same melancholy.

Ironically, Darling has suffered from a tendency for critics to examine Diana only from the outside, or to see her as somebody who understands her own agenda. She has been written off as simply lacking in morality, so that the film becomes nothing more than a meandering social satire. If we view her, instead, as more of a 20th Century Faust, her insecurities making her prey to a surfeit of temptation, then the film unfolds instead as a compelling character study addressing an infernal journey that we are all invited to make.

Reviewed on: 01 Jun 2025