|

| Camilla Damião, Rejane Faria, Cícero Lucas and Carlos Francisco in Mars One Photo: courtesy of Array Releasing |

One of last year’s festival successes, now about to be released on Netflix and in select cinemas, Gabriel Martins’ Mars One is a portrait of an ordinary Brazilian family each of whose members seems to be pulling in a different direction. There’s mother Tercia (Rejane Faria), trying to hold everything together but frustrated by the sense that life is going nowhere; father Wellington (Carlos Francisco), an alcoholic struggling to stay on the wagon and pinning all this hopes on his young son; the son, Deivinho (Cícero Lucas), who risks disappointing everyone if he gives up on his talent as a footballer to pursue his true passion, astronomy; and the older sister. Eunice (Camilla Damião), who is trying to support her brother but also to break away and start an independent life with her first girlfriend. Everybody is talking and nobody is listening, but somehow, in all the chaos, Gabriel finds a thread of positivity, drawing on their mutual love.

We met during the darkest days of the year in the Northern hemisphere. I was wrapped up in a blanket, in the dark; he was in bright sunlight. The mood in Brazil was buoyant, just a few weeks after the election which saw the defeat of Javier Bolsonaro. Things felt very different back when Mars One is set, when Bolsonaro had just come to power. I ask if that was an influence on the story.

“Yeah,” he says. “Not in the genesis, because the genesis of the film was in 2014, so four years before. I guess it was kind of lingering in a way in, in Brazilian politics, some kind of turmoil, of identity crisis. There were generation gaps coming across our decisions, our encounters. I think this is something that was happening all over the world. But I think in Brazil, since it was an election year in 2014, and it was a very tough election, and we had the World Cup, that was when I started to connect things to connect football and soccer, in a way that we could understand society from it. And this historical dream, in Brazil, of having a successful idol in soccer.

|

| Cícero Lucas as Deivinho Photo: courtesy of Array Releasing |

“I think when I wrote the film, I always wanted it to be contextualised in the time when we shot the film, so we can feel the surroundings and see what it was like in pop culture. And that happened to be two weeks after Bolsonaro’s election. So that was very much alive in our brains, in our feelings. It was a very big event in Brazil, a surprising event that was also talking a lot about what this film was, what this film could talk about, in many ways, which is dreaming of overcoming a difficult time. I think Bolsonaro represented everything that this family does not represent, I think he was like a step backwards when this film was aiming for the future. So I think it made sense.”

There's an interesting scene early in the film when Tercia is caught up in a bomb scare which turns out to be a prank, and it creates a sense of tension throughout the film. I note that, to me, this felt similar in some ways to the election of Bolsonaro, because of the uncertainty and worry that something bad would happen.

“Yeah. I think those things just were starting to connect, because this is, as I said, an idea that came long before. I think it was also this idea of things shifting in our cultural environment, because I think the thing about Bolsonaro, the presence of these events, and this idea of being contextualised in the present time, when we shot it, is because this is a film about cycles. It’s a film about waking up, going to sleep, it's a film about the Earth going around the sun and things like that. I think this idea of daily routine, which is the way that film is structured, as a script, and in editing – I think when that bomb comes to the story, I think it's telling that even though we are pretty much accustomed to that daily routine, sometimes things can shift. And we all get affected by things. So we can compare that we could have this relation with the politics and this very deep feeling, and the serious things that the character of Tercia is facing.”

It seems very relevant to Wellington’s experience as well, because that kind of routine is really, really important when someone's struggling with an addiction.

“Yeah, I think in the AAA meetings when they wish 24 hours, even that was coming across, this idea that we really have to live each day at a time because everything changes so much The film is based in three to four months in this family’s time. So I think this could be this reflection of time; it could be a way for us to think about life in a different way. I think this film is always talking about life and how life can change in a second. Sometimes you're alive. Sometimes you're dead. And sometimes we are okay. Sometimes we are very sad. I think Mars was thinking about something that is larger than life, as a space trip. I love how the film is about space and at the same time about small things.”

That's very much there in the final scene, I suggest, when the family members come together and look at the stars.

|

| Camilla Damião as Eunice Photo: courtesy of Array Releasing |

“Yeah. I think the beautiful thing about the stars, for me personally, is that at the same time is something very expanded, we feel very small. And this is a wonderful feeling in a way. But at the same time I remember, as a kid, sometimes picturing as if the sky would fall all over me. There is more, which is having a sense of wonder, but at the same time, a sense of danger in a way. And I love these two feelings that we have in the film. I think it’s also about these parallel feelings, about paradoxes.”

We talk about Eunice, who is at a transitional point in her life and is living in two world, slowly breaking away from her family and forming a new relationship.

“She was very much based on many friends that I have, but also, at first, it was about me looking at that political turmoil of 2013, 2014. And I see many schools having strikes to have their demands, priming girls as political figures at a very young age. And I'm starting to think of Eunice as a political figure. That's why I made her study law and things like that. But I think as I developed her, I was thinking about bringing something closer to her, something that will be very personal, something that could antagonise the family. And I think that this idea of having, inside this film, kind of a coming of age story of someone entering adult life by leaving the nest, I think it was something very important to have this organism of the family being broken by a choice that the family doesn't understand or is kind of supportive of, but not entirely.

At the same time, Eunice is struggling very much to come out and to bring this identity to her family. And this being a very important moment for her to to construct herself as a human being, as someone that is going to study and to make her own choices, as not wanting to be treated as a child anymore. So this idea of someone becoming an adult was something that I was very interested in. It could be responsible for having her brother actually chase his dream. Now she has some money, or she started to have some money, she can make these decisions. So I think this idea of her becoming empowered, in that sense, was interesting to me with all the contradictions buried within her.”

Moving on to the brother, it strikes me that Brazil is perhaps the only country in the world where parents would be disappointed that their son wants to become a scientist rather than a footballer.

He nods. “I think this is also a film about that, about this idea of that we push culturally in Brazil, but some other places too, that we have to find this lottery ticket, and soccer being a way, even though it's probably way harder for him to be a successful soccer player than a scientists. I think this idea of especially Wellington is a thing of his generation, the father's generation, that is very passionate with soccer...I think this passion overcomes even the possibility of listening to something that could be way more beautiful and make more for the family, but it’s just this blind passion that Wellington has. I also kind of understand. It’s something that he uses to escape. In this film everyone is right, in a way, and nobody is wrong. I think this is something that I was trying to achieve.”

|

| Carlos Francisco as Wellington Photo: courtesy of Array Releasing |

Tercia also longs for escape, and a conversation in which her employer chats casually about a holiday in Europe, which she could only dream of, points up the gulf between classes.

“Yeah, that was pretty much talking about reality, people that are really close to me. People that still to this day are struggling with professions where they are exploited. I think it was a fair portrait of Brazil, this idea of we have this reminiscent employment state of mind that comes from slavery, and that comes from how the country was formed – by war and exploiting the indigenous community and black community that came from Africa, slavery, everything that we know about that. And how that is in some ways very obvious.”

Sometimes, he says, it’s possible to look at events today and see a very precise reflection of events a century or even two centuries ago.

“But some things that are very subtle. This kind of relationship might seem friendly, but in the end, they are full of cracks that you can see through and see that some things were just not overcome in our country, like, yeah, you go away, go on a trip, and you don't worry how that person is going to find another job or how that person is going to have enough money for the month. So it's funny, because when I showed the film here, a lot of people are just really starting to see themselves in that situation. And sometimes, even I see myself doing that. I think sometimes, even though we are concerned and thinking about those things, sometimes we betray ourselves, the way we behave by not thinking that much about the other person. So it's also about that, in a way – to try to understand Brazil, and how we naturalise certain types of behaviour that shouldn't be normal.”

That would seem to depend heavily on communication and thinking about other people's points of view. Within this family, nobody is really talking to anybody else about what matters to them. That must have presented a structural challenge from the outset, to talk about these four people and the different things that they want in life without any of them quite seeing what the others are doing until the end.

He nods. “I think you've pretty much nailed that point about communication because it is something that I have actually had in my family, especially my father's side. That is a very quiet family that in many times didn't actually speak about problems. They rather like sweeping the dust under the rug, and it's a very common thing. Also, my state is known for the mountains. We use that as kind of a metaphor, that people from my state are usually very quiet people. Sometimes I think it's problematic in a way, that you start to build things up. So they're very deep down inside.

“That becomes, sometimes, alcoholism, that sometimes becomes like this idea that you can stand up for your father or some figure of authority, even if you think that person is wrong. So I think that silence, that deep silence that lingers for a long time, I think it's something that I experienced myself, the way I was brought up. It's not very violent in an explicit way, but it's just there, you know? With my father, for example, there were things that I was afraid to stand up for, to him, and to contradict him, even though he was not a violent person or anything like that. It's just the silence. And this idea of this father figure that you have to respect, it's something that I also wanted to talk about. It's not an autobiographical film, but it's coming a lot from feelings and atmosphere that have been around my life for many, many years.”

|

| Rejane Faria as Tercia Photo: courtesy of Array Releasing |

How did he work with the actors to get them to feel so much like a real family whilst also showing us that distance and silence?

“In many ways, I think I was very lucky. I did the casting myself. The mother and father, they already been working with me in short films and other projects, so they already knew each other. We were pretty much already like a family before making the film, because we're very friends. We make made a lot of films together. We are comfortable around each other. This was something very, very important to me, because I had a lot of faith in them. It was the first time they played protagonists, they always look like supporting actors. This was something huge as well, and I think they embraced that opportunity with a lot of grace.”

Rejane brought Camilla with her from another project, he explains, and was already treating her in a motherly way.

“She’s very smart, very interesting. She works with visual arts. And Cícero is a kid that I just found playing Samba, since he was like eight years old, seven years old. He's a professional percussionist. He plays with his father. The band that is playing Tercia’s birthday is the band that Cícero plays in, in real life. He just had this wonderful feeling about what I wanted. And when they came together, it was very, very natural. I think the four of them, they have a huge, huge heart. And that is very important, because they will so open to that experience...we rehearsed a little bit, but it didn't even have to be that much, because they already had chemistry from day one.”

We talk about the locations.

“Some places were locations that we pretty much changed everything. The kids room was pretty much from scratch. We just found like a space that we would be interested in. We didn't have enough money to actually shoot in the studio and things like that. So we actually found real houses, but we built everything. We brought all the furniture is so it's pretty much an identity that is built from from zero in many places, especially the family house, how the family actually leaves there.

“Our production designer, Rimenna [Procópio], was very talented to understand how small things could tell a lot of stories there. I like how production design, they kind of come up with their own stories. And so I was very happy to be able to do that. I think we had this intention of it pretty much feeling like you are watching a documentary, but in fact everything is very scripted, very planned.”

They shot pretty much exactly a year ago, he reveals, and at this time of year there’s a lot of heavy rain. “It rains and the sun comes out of nowhere, so the light changes a lot. So we pretty much hid that whole house with black cloth and artificial lights. So when you see the film, actually everything is artificial in a way, because we didn't want to we didn't have time to kind of wait for the sun to change.”

That adds to the feeling of intimacy in the film, I tell him. But I wondered how much he was forced to keep the cameras in close in those spaces, because there wasn’t much room to move around.

“It was kind of an actually an aesthetic choice, in many ways, because we found places that we had room. But I think this started to show like a close up feeling for me at times. I think that was kind of reminiscent of John Cassavetes in Faces, but also A Woman Under The Influence – films like that were influencing me in many ways. I think that was a choice to actually complement their faces and have this idea of the extra film. Each one of the characters has a moment in the film where we pretty much stay on their face for a very long time. And you listen to everything that is happening to them.

|

| Brother and sister Photo: courtesy of Array Releasing |

“This is most radical in the Tercia scene after the break, when actually I didn't shoot anything else. It was not an editing choice to just stay on her face, it was just what I shot. Because I had this idea to listen to this environment, so you really have to listen to this person. I think it connects to the idea of empathy that I was telling you about before. You have to listen more to what the person is saying, but also the reactions.”

They had six weeks to shoot in, he says.

“We had a few scenes that we cut out. In the storyline with Eunice, we had more things in the university. And actually, the film has had a whole different opening, in the World Cup of 2014 that Brazil lost.” It was about building up a sense of the past, he says, but in the end he realised that we could understand enough about that from conversations and events in the main timeline.

We talk about the outdoor locations.

“That was actually natural for my city of three million people. Sometimes you have these environments that are not exactly photo cards. So I'm interesting to see that as also a documentary of that place at that time. I love fiction films to have also this kind of depiction of a memory. When we make a film, we're kind of making a movie museum of the time when the film was made. And I think as a museum of who was I, who was everyone in the production at that time, what people were thinking, and I love that.

“The same thing goes to the location and the way we portray the city, I think it becomes just a documentary of that environment. And also to understand that characters and the dreams they have, they have that environment to build up in. Actually Deivinho builds up this telescope from trash basically, that he finds. So I think this also has an important meaning culturally. I try not to look away from that, because it's just reality.”

It was still important, he says, to end the film on a positive note.

“We are living a very cynical perspective about social inequalities, politics, which is rightful to do so because we are constantly being disappointed by human beings and politics, particularly. But at the same time, I was thinking: how can we portray a vision of the future that is optimistic? Because I'm that person. I'm just putting out there who I am. But at the same time, not being naive, and not being delusional, to think that some things are possible. And I think this idea of this dream that is moving the film, which becomes the title of the film, for me is a kind of utopia.

|

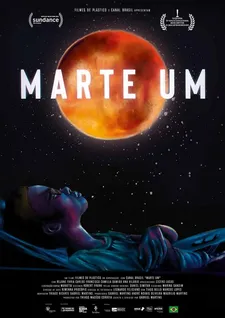

| Mars One original poster |

“Sometimes when people talk about utopia, it seems naive in a way, but actually it's just something that you have to aim for. At least wake up and do something with your day and try to be productive. Not in a capitalist way, but be productive in a way that you can affect other people. You can do better yourself in many ways.

“Sometimes I'm a pessimistic person as well. Sometimes I wake up in not a very good mood. And that that is a fair feeling. I also made films that are not so uplifting, but in this story, I think I had to do that. I was wishing at the time, with everything that was happening in the world – and now, after going through a pandemic, the Bolsonaro government – I think it's an interesting message, and I think it's an interesting feeling. I think it makes you feel good. But not make you feel good so you can avoid to look at things that are bad for the world. No, it's just understanding what the word is, realistically, but trying to have another perspective and just making something out of it.”

Mars One opens on Netflix and on select screens on 5 January.