|

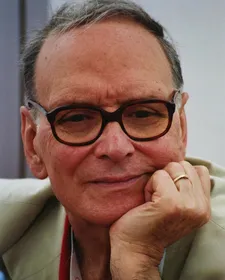

| Ennio Morricone, who has died at the age of 91 Photo: Unifrance |

|

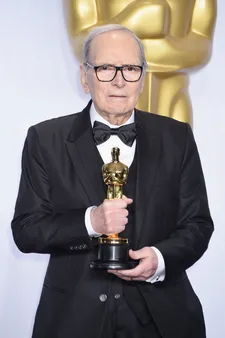

| Ennio Morricone with his Oscar for The Hateful Eight Photo: ©A.M.P.A.S.® |

There’s a reverential hush that had descended over the terrace of a Swiss fairy-tale castle of a hotel overlooking Lake Maggiore. Phrases with the word “maestro” floated across the evening air while a retinue of young women seem to be dancing attendance.

The subject of all the attention was a grey-haired man then in his seventies, talking genially at one of the tables, often gesticulating wildly as if he was a conductor on a podium - and he could well have been because this was Ennio Morricone - whose death in Rome at the age of 91 has been announced. His signature has appeared on the scores for countless memorable films, including Once Upon A Time In America, Days Of Heaven, The Mission, Cinema Paradiso and The Hateful Eight as well as Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Westerns. Often his music actually was more memorable than the film itself - and you can read our dive into the score of The Good, The Bad And The Ugly here.

By the time I was ushered in to his presence the maestro, often described as “the Mozart of film music”, had settled into his loquacious stride. He had been a special guest at the Locarno International Film Festival as part of a series on music and the movies - and who better to give the benefit of his experience. He returned in 2018 to give a special concert in the Piazza Grande.

He was modest to a fault, and shrugged off any attempt to elevate him to the deity - “maestro” was as far as it went. When the denizens of Hollywood came running to tempt him out of Italy after the success of his trademark scores for Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns he resisted firmly.

Morricone lived and worked in Rome, where he was born in 1928, all his life. Although he has collaborated with some of America’s finest including Warren Beatty, Brian de Palma and Mike Nichols, he eschewed any pressure to speak English (our conversation was translated).

“Some might say that remaining in Italy was a bit of a limitation but I don’t see it that way. I prefer to live in Italy,” he said smiling contentedly. After missing out on many occasions, he received an honorary Oscar in 2007 although he had been nominated several times, including his music for The Mission about which he did feel rather cheated.

“It was the year [1986] when Round Midnight won which was a bit strange because that was not even an original score - it was a very good arrangement by Herbie Hancock but he used existing pieces while The Mission was an original concept,” he explained

|

| Ennio Morricone with his conductor's baton in hand Photo: Unifrance |

His influence on decades of film music is incomparable. He was a musically gifted child, who won a place at the Santa Cecilia Conservatory when he was only 12. That gave him his musical theory and grounding, allowing him to find work as a trumpeter.

He said: “In the very beginning I started by doing musical arrangements for radio, television and for record companies. My start in cinema came very simply - a director Luciano Salce had heard of me and asked me to do the music for one of his films. It was in the Sixties - from then on it’s difficult to trace my career because it all came in fits and starts.

“My influences came from jazz as well as popular music and also from some of the great composers such as Boulez and Stockhausen. I was also interested in experimental and avant-garde music and all of that has gone into what I write.

“I’ve tried to change with the times and also to take into account the vast strides that have been made in recording techniques - the soundtrack in cinema now has far greater clarity than when I began 30 or 40 years ago."

When Morricone began work on a score, he did so with the idea of a piece of music that can exist without the images - the music, he believed, had to work on its own before it could be adapted to serve the purposes of the film and its director.

Quentin Tarantino, who professed himself a fan, used some of his compositions for the Kill Bill films, Django Unchained and Inglourious Basterds. Morricone once said that working with the director on The Hateful Eight - for which he won an Oscar in 2016 - was “perfect ... because he gave me no cues, no guidelines.I wrote the score without Quentin Tarantino knowing anything about it, then he came to Prague when I recorded it and was very pleased. So the collaboration was based on trust and a great freedom for me.”

He added: “My criteria is to choose whatever I find interesting myself. When I have refused films it is usually because I do not get along with the director. But once I accept, then I am always co-operative and never critical and try to make the best of it. I see bits of the film as it goes along but always wait until the final cut before locking in the ideas for the final score.”

|

| Ennio Morricone: 'My criteria is to choose whatever I find interesting myself' Photo: Unifrance |

He believed that cinema had a symbiotic relationship between music and images. He was never any good at predicting what films would succeed and which ones would fall by the wayside. He considered it was easier to have a success with a mediocre score in a good film than with a fine score for a bad film - although he was happy to concede that music sometimes can help to save a lacklustre film.

In his early years, he was associated with Westerns but pointed out that out of his 400 or so scores only 30 of them were for cowboy films. He has turned his hand to most genres from thrillers to love stories and horror movies. Without knowing it, Leone and he had first met each other in the same primary school but only came together professionally 25 years later.

He wrote more personal music other than scores and has conducted many concert performances of his work. He conceded that it was around film music that his reputation revolved but he was keen to remind people of other talents.

He displayed few, if any, signs of slowing down his output, suggesting he might have some way to go to catch up with the frenzy of activity surrounding a Mozart or a Bach. His creative satisfaction still stemmed from the same results: a job well done - and an honest day’s toil. “That’s what I’ve always done,” he proclaimed with a flourish.