|

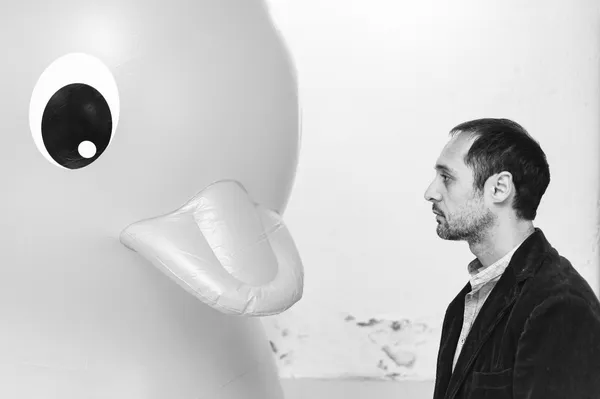

| Alessandro Aronadio: 'Time constraints are helpful but it's also super challenging, so it pushes you to find solutions in a very short time' |

Alessandro Aronadio’s absurdist comedy Orecchie (Ears) is screening as part of the Scottish Italian Film Festival. The black-and-white film follows a day in the life of an unnamed anti-hero (Daniele Parisi), whose problems start when he wakes with an unsettling and constant ringing in his ears – and that’s before he spots the note on the fridge telling him his friend Luigi has died. Bad enough in and of itself, but he doesn’t know anyone called Luigi.

The film then follows him through a succession of often-surreal tragicomic encounters as he comes to learn something about himself. The film was made as part of Venice Film Festival’s Biennale College project – which sees filmmakers mentored to produce their films within a year and on a tight budget, with other notable films benefiting from the system including The Fits. We caught up with Arondadio to talk about the film.

The aspect ratio changes as the film progresses, beginning at 1.1 before gradually expanding to 1.85.1, why did you decide to do that?

The idea was to show the increasing of the space of the world of our protagonist. He's a man who starts the day by shutting the door on the outside world in the first scene and then, little by little, he understands that he has to open his mind and world to other people. Even if he thinks they are crazy or ignorant, he has to leave them space to be part of his world otherwise, he would die alone, forgotten or invisible. So, the idea was to increase the space with a cinematographic trick, let's say. I really wanted to start the movie with the square aspect ratio because one of the influences on the movie is the old slapstick comedies - and that was the traditional aspect ratio of those films. Then, little by little, increasing the space and making the aspect ratio bigger until a classic 1.85.1

How much of a challenge did that pose to you as a filmmaker, because you're restricted in what you're shooting in those very early scenes and then you get more freedom as it goes along.

It was a challenge. And, we didn't need to have another challenge, we had so many, because of shooting in three weeks and with the Biennale College budget of 150,000 euros but we really enjoyed the creative freedom of poverty. So, we thought that was probably the only chance we would have to try different things. So, we thought, let's add another challenge to the shooting. What we did was to create a moving aspect ratio that followed us during the shooting on the monitor, so on the monitor I was quite sure that how the movie at the end would be really close to the what I wrote. I knew the aspect ratio for every particular minute of the movie, so we framed based on that.

Speaking of framing, I'm interested in the way that you use artwork in the film as well. There's a lot of very large art, from walls outside with graffiti or a mural dominating a room.

What I wanted was to show a different Rome - a Rome in black and white. Rome not just like a classic touristic postcard. So, I picked some locations that are artistic in a modern way. There is kind of a cliché that Rome is the beautiful ancient city trapped in its past. All this street artworks are part of the contemporary side of Rome that's important. At the same time, all these pieces of art, the way in which humanity wants to stop time and give their contribution and give the sign of their being part of history. One of the bigger themes in the movie is being somebody, having an identity, being part of the story, let's say, the fear is anonymity. So those works are connected with the film, in my opinion, they are the artist's way of saying, 'I am here, I am part of history'. Our protagonist doesn't even have a name, he needs to have an identity and one of his fears is to live his life like this.

How hard was the film to cast?

In the beginning, I thought the character should have been older. I've known the actors since my first film. He played a secondary role that I cut in the editing room, so I needed to give him something back. I auditioned him for another role and he was great but then I just kept thinking about him and asked him to do this too. There are little miracles in cinema, when you just write a character or story and then you just see the character in front of him. That's what happened when I saw Daniele saying his lines.

In terms of the process of the Biennale College, how much of a challenge is that, because of the time constraints?

Time constraints are helpful but it's also super challenging, so it pushes you to find solutions in a very short time. In some ways it's super-frustrating but it can be very creative too. I think being pushed is mostly a gift. I am generally a scriptwriter and if I have two months, one is for checking my email and going on Facebook and reading newspapers and walking and then, when I'm super-late, that's when I start to write. It was just like having the last 15 days without the first one month. Of course, it was nine months to make a movie, it's like a pregnancy.

There is quite a lot of philosophy in this film - you come from a philosophy background - were you conscious of that as you were writing it.

|

| Alessandro Aronadio: 'We really enjoyed the creative freedom of poverty' |

I studied a lot of Greek philosophy and most of us have this attitude to ask so many questions. So Ears for me was a kind of white flag. Like saying, this way of living does not work at all. The hip-hop director says 'Simplicity is difficult to achieve'. All the other people around the protagonist have their own way to stay in the world and to find a solution. What the priest says, that living with something is important to survive.

Religion is used for comedy in the film but it comes out of the film in quite a positive light, on the whole.

Yes, it works. It's a critique but there's also admiration for how it works. Everyone may look crazy or stupid but they have something he doesn't. It's like he has to take up pieces of a puzzle from each encounter and at the end composes the image of himself. He realises that 'himself' is not working, he has to change himself.

Are you working on other projects as well?

During the film, I had to write another two scripts for other directors, so I don't know how I survived. It was a hard time for me. I have a few projects now that I hope to do. I would say the success of Ears surprised us, too. So, I hope that I'll have the chance to pick my most difficult and challenging project because I'd love to make that film.

Will it be more comedy?

It will be a kind of strange mix between comedy and noir.

Ears is showing at Edinburgh Filmhouse tonight (March 7) at 6.10pm and at Glasgow Film Theatre on Friday, March 10 at 8.45pm. Read more about the festival line-up.