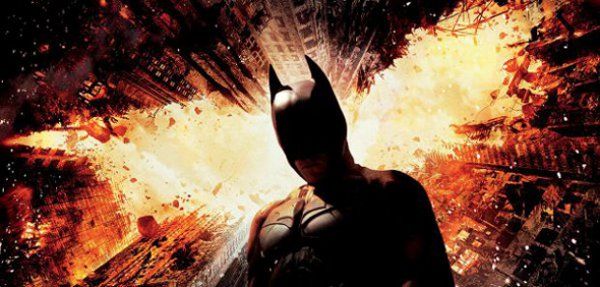

Yesterday a masked man strode into a Aurora, Colorado screening of The Dark Knight Rises and opened fire, killing 12 people and injuring 50 more. Already, commentators are starting to talk about copycat violence. There's just one problem. This screening was a midnight special, the first of the film's release. The projector had only been rolling for ten minutes. Suspect James Holmes wasn't a member of the press. He couldn't have seen the film.

Cinematically inspired violence certainly exists, as a number of high profile cases demonstrate. The question is, do films cause crime or do they just inspire those who were already going to commit it to add certain stylistic flourishes? Most of those convicted of violent crimes inspired by films have been ruled insane. There is, as yet, no evidence of a film persuading a mentally normal person to kill - unless, arguably, you include wartime propaganda and films aimed at stirring up race hate, which are clearly part of a wider social context. Furthermore, just to cloud the issue, some high profile cases supposedly involving films weren't really linked to them at all. For instance, despite newspaper speculation there is still no evidence that child killers Jon Venables and Robert Thompson ever saw the copy of Child's Play 3 that their uncle owned. An attempt by one of the Washington Snipers to claim that his repeat viewing of The Matrix proved him inculpable by reason of insanity was roundly dismissed by a jury.

Perhaps the most famous case of film-inspired violence remains the 1981 shooting of President Ronald Reagan. John Hinckley Jr, who suffered from a narcissistic personality disorder, became obsessed with the film Taxi Driver and convinced that its protagonist, Travis Bickle, was speaking directly to him. Identifying closely with Bickle, he believed that emulating his actions in shooting a high profile politician would win him the attention of Jodie Foster, who plays a child sex worker whom Bickle tries to save in the film. Luckily for Reagan, the shooting wasn't fatal, though his press secretary James Brady was left partially paralysed. Hinckley was captured alive and has been in a secure hospital ever since; he is only now thought well enough for possible release. Foster was traumatised by the incident and still refuses to discuss it.

Similarly high profile was the violence associated with the 1971 release of A Clockwork Orange. Several young people accused of violent attacks over the next few years cited the film as an influence, though prosecutors were loathe to give this too much credit. The most clearly related incident was a gang rape during which the attackers sang Singin' In The Rain in the manner of characters in the film. This incident so horrified director Stanley Kubrick that he withdrew the film, though it continued to circulate in underground cinema clubs and it was eventually released on DVD in 1999, to no noted ill effect.

"I think Kubrick was wrong to do that," said director Oliver Stone of the film's withdrawal, speaking to the Guardian in 2002. "I'm a big fan of Kubrick, but he was a paranoid man. He reacted to the hysteria of the mob. He crumbled when he should have stood up and defended his work."

At that point, Stone was entangled in controversy of his own. His 1994 film Natural Born Killers, itself a comment on the glorification of violence in the media and based, like Terrence Malick's Badlands, on the real life Starkweather/Fugate murders, it was the alleged inspiration for a series of attacks by Sarah Edmonson and Benjamin Darrus. In 1995 the young couple took LSD and watched it on a loop before setting out on a shooting spree. Fortunately only two of their victims died but one of those happened to be a friend of the author John Grisham, who helped finance a lawsuit against the film by relatives. Though the suit was unsuccessful, it caused lingering damage to Stone's reputation, and he spoke of his frustration at being criticised for promoting violence when he considers it a natural part of human nature which is often mishandled by the wider media.

Nowhere is that mishandling more apparent than when it comes to suicide. After extensive, often lurid reporting of the 1962 suicide of Marilyn Monroe, suicide rates around the world spiked. Psychologists stressed that, whilst it is difficult to find a clear evidential link between media content and homicide, when it comes to suicide that link couldn't be more obvious. Guidelines on the reporting of suicide have consequently become a standard part of journalistic training but how it should be managed in film is more controversial. The Deer Hunter (1978) has been accused of inspiring several suicides with its Russian roulette scene. Experts say the key thing is to avoid showing methods of suicide, which is why many film suicides happen offscreen and are referred to only obliquely, but obviously this is more limiting for a dramatist than for a journalist.

One thing film censors are always very cautious about is easily imitated violence, especially in children's films or in contexts where adults might not expect the results to be very serious. Inevitably, problems still occur. Five cases of poisoning were linked to the 2005 film Wedding Crashers, in which Owen Wilson's character spikes a drink with eye drops to cause diarrhoea. In each case, the defendants said they had no idea that what seemed like a joke could have dangerous consequences, with one victim suffering severe headaches for several months after the incident occurred.

In several cases individuals arrested for assault or murder but found to be insane have made reference to films it's unlikely they actually saw. Once a film has been released, ideas within it often circulate more widely than the film itself, and this is all the more common in the case of films that attract controversy due to violent scenes. If anything, The Dark Knight Rises is less violent that its trailers and pre-release publicity have led people to expect. It's possible that Holmes was inspired not by the film but by stories and ideas relating to it that were already established in public discourse - but how these may have interacted with his existing issues remains to be seen. He had no known mental health problems, though New York Police Commissioner Ray Kelly described him as identifying closely with Batman character The Joker. Doubtless more will be known once the dust has settled, but for now we should be wary of making any straightforward links between film content and his violent actions, and certainly wary of assuming that one caused the other.