Eye For Film >> Movies >> Christy (2025) Film Review

Christy

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

“Nobody wants to see a butch girl fight,” says coach Jim Martin (Ben Foster), encouraging his talented young protegée to grow her hair. What if people thought she was a lesbian? It wouldn’t be the first time that those close to her thought that, on account of her having had a girlfriend for several years, but this is West Virginia in the mid-1980s and nice girls aren’t supposed to do that sort of thing. “What you’re doing isn’t normal, and we want you to have a happy, normal life,” says her mother (Merritt Wever), whose super-soft voice is the cruellest of all.

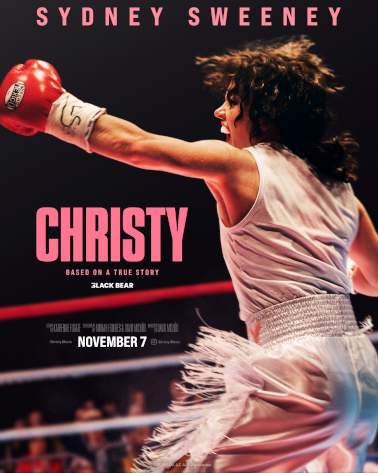

Do cinema-goers want to watch a butch girl onscreen? The assumption that they didn’t was, historically, one of the challenges with getting stories like this told. Of course, Sydney Sweeney’s offscreen image has been marketed as highly feminine, and in borderline creepy ways, given that, though she’s 28, she can still pass for a child. As a consequence, she’s been widely underestimated, and the performance she gives here, slipping easily into Christy’s skin, is going to knock some people for six. Though she’s every bit as convincing as the 41-year-old version, she uses that childlike quality to give Christy a sweetness that makes her easy to root for in the early scenes. The young boxer comes across as an adorable kid, regardless of how she presents herself – and for that matter, regardless of how many people she’s punching out in the ring.

This sweetness makes the events that follow all the more unpleasant – especially as viewers will know that this is a story rooted in truth (even if it downplays the cocaine). Success comes so easily to Christy early on that one wonders what’s going to happen to her when she eventually loses, because nobody seems to have prepared her for that – but the real danger is not in the ring. What starts out as the sort of carefully balanced bullying often present in a training relationship turns into something much creepier as Jim, 25 years her senior, exercises more and more control over her life, then pressures her into marrying him.

The real Christy has had plenty to say about what followed and viewers can easily look it up if they wish to – in light of later events, it’s not difficult to believe. Director David Michôd is circumspect about what he shows here. There’s an early glimpse of an incident so horrific that you might find yourself wondering if you really just saw that, and of course that’s part of how the psychology of abuse works. Most of the time, we don’t see any kind of violence, which makes room for the film to explore subtler aspects of the change Christy goes through – the disappearance of that smiling, goofy kid into an unhealthy sort of adulthood where she is less and less certain of her own identity. The only witness to it all is her beloved little dog, and by cutting to its face at crucial moments, Michôd keeps us from getting sucked too far into the illusion that this is normal.

Part of what gives Jim his power is Christy’s own obnoxiousness. What was amusing in a kid becomes ugly in an adult. Her gutsy trash talk gives way to homophobic jibes. She ditches friends who have become inconvenient, and stubbornly turns away offers of help from the only people still close enough to be concerned. A scene with her mother hints at where some of this may have come from, and points up the large scale cultural expectations that contribute to women’s vulnerability. Merritt is superb, capturing a certain style of sweet Southern ladylike brutality that will send a chill down the spines of people who have lived in that environment. This cultivated artificiality sits starkly at odds with the gauche candour of the person Christy can still be when things go her way.

As the rest of her life falls apart, her talent remains. Her signature style, highly aggressive and excitable, isn’t easy to portray dramatically. It takes a while for her to develop tactical skill, but Michôd handles the fight scenes well, keeping the camera in close, stressing the intimacy and immediacy of the experience. This is the only context in which she feels free, and the shift in styles emphasises the way that she has compartmentalised her life, perhaps helping viewers to understand that the power dynamics in an abusive relationship are rarely just physical. In her personal life, Christy simply never has the initiative – until she does, and that, as anyone who has been through it will tell you, is when things get really dangerous.

A well constructed script balances the film’s main themes in such a way that the story never drags but neither is it too precipitous. Christy’s own frustration carries us through the periods when her career is moving slowly because there are few women capable of giving her a difficult fight. The freshness of Sweeney’s performance keeps it from feeling preachy or overly familiar. Despite the well-trodden subject matter and occasional heavy-handedness, it feels true to its characters and very particular, very personal. One wonders how the public might feel about butch woman being celebrated at the Oscars.

Christy is in cinemas across the UK & Ireland from 28 November.

Reviewed on: 03 Nov 2025